How would Donald Trump fare in a jury trial? Why an indictment against the former president is more than likely

The House select committee investigating the Jan. 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol has shed light on the alleged egregious, and at-times unbelievable, actions of former President Donald Trump.

Those first-hand accounts from witnesses close to him at the time detail a range of potential crimes committed by Trump, from inciting a violent insurrection that resulted in deaths—and refusing to act to stop the attack—to his efforts to overturn the 2020 election.

Many legal experts, including those at Northeastern, say there’s enough evidence to charge the former president with crimes, including seditious conspiracy and pressuring public officials to undermine the election results.

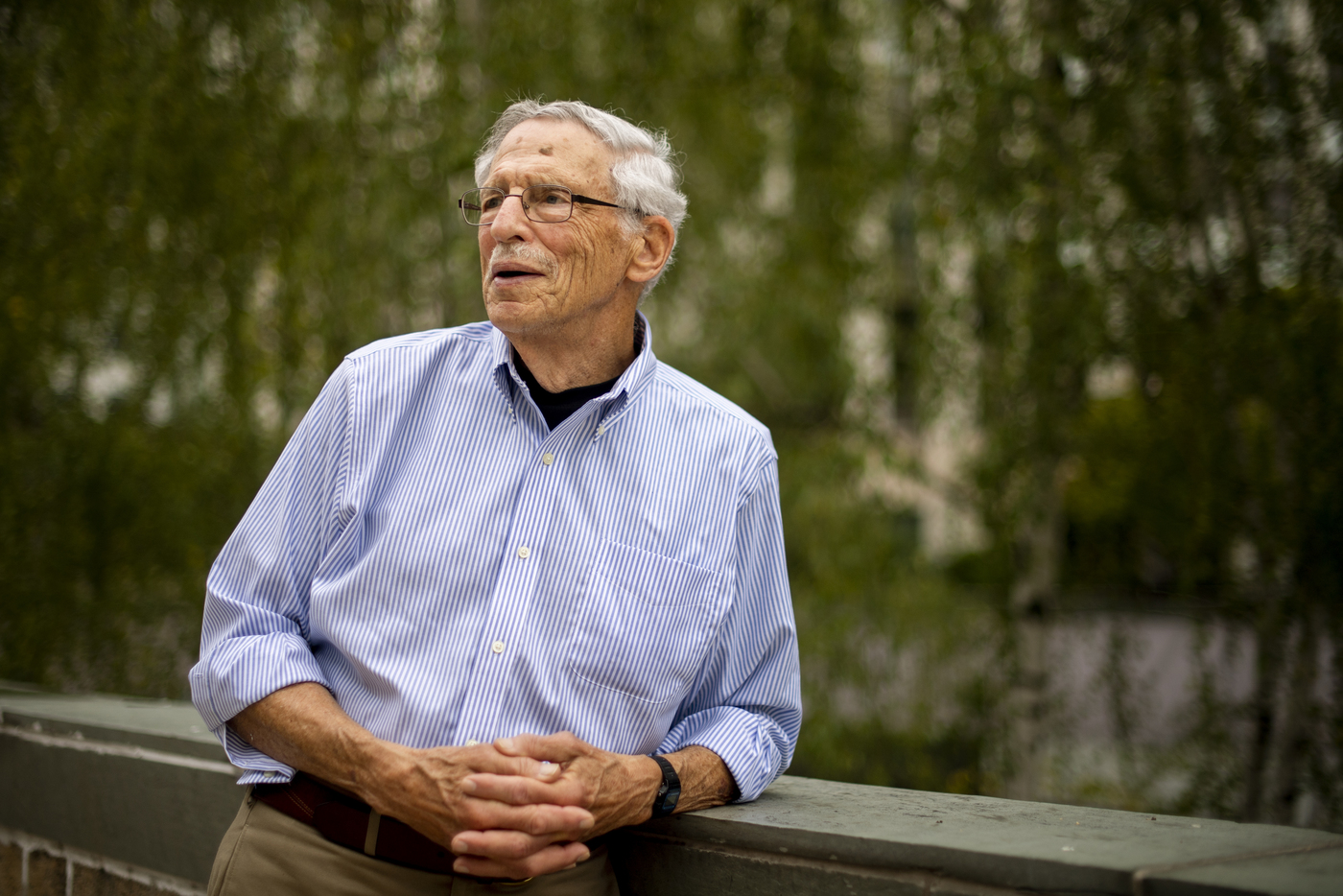

“It is clear that there is enough evidence to indict and convict the former president of conspiracy to defraud the United States, illegally interfere with the electoral count and even sedition,” says Michael Meltsner, the George J. and Kathleen Waters Matthews Distinguished Professor of Law at Northeastern and author of the civil rights-era novel Mosaic: Who Paid for the Bullet?”

“Whether such charges would lead to a conviction would, of course, be up to the trial jury,” he says.

But Meltsner says he also believes the evidence shows that Trump acted with “criminal intent,” a thorny legal concept that experts suggest would present prosecutors with trouble were a case to move forward against the former president. In particular, experts question whether Trump knew—and therefore believed—that he had lost the 2020 election to Joe Biden, establishing that he acted with “guilty mind.” Such efforts range, according to witness testimony and numerous reporting, from pressurring Georgia election officials to come up with enough votes to reverse the state’s election results, to overseeing a scheme to install fake electors in specific states Trump lost.Meltsner says claims that prosecutors would have difficulty establishing criminal intent, based on the sheer evidence of numerous other crimes, are unpersuasive.

“A [person’s] conduct, as well as inaction, under the particular circumstances demonstrates intent; some picture of an inner mental state has never been required,” he says.

Despite apparently widespread agreement that the Department of Justice has a clear-cut case against Trump, many observers worry that if Attorney General Merrick Garland were to pursue prosecution, the move would be seen as political. The House select committee itself, which is composed of seven House Democrats and two Republicans, has no prosecutorial power—but the body can make a criminal referral to the DOJ.

Even the criminal referral itself carries concerns of politicization at a time of heightened political polarization and increased distrust of government institutions. But Meltsner says the DOJ couldn’t possibly separate out the political ramifications from its own decision to pursue charges. At the same time, some experts anticipate there could be public backlash if the Justice Department doesn’t pursue charges amid the overwhelming evidence of wrongdoing.

“The political implications of charging Trump are not supposed to weigh on the DOJ decisional process, but experience teaches that, even if denied, such calculations are often present when public figures are involved,” Meltsner says.

Justice Department officials should act regardless of what the public thinks, says Costas Panagopoulos, head of Northeastern’s political science department and editor of “American Politics Research,” because trust in the country’s institutions is at stake.

“Certainly, part of the calculus is partisan and political,” Panagopoulos says. “But at the same time the Department of Justice has to do its job, and if segments of the public perceive that as partisan and political, then so be it. If the [DOJ] doesn’t take a stand to protect the electoral process and democracy in America, what is its purpose?”

“They have to send a strong signal, and the hearings that have been going on could conceivably provide the public with enough factual evidence that would justify a criminal indictment of Trump, thereby helping to solidify the perception that it is not purely a political move,” Panagopoulos says.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu