After the death of his son, Darin Detwiler became a food safety champion. Now, he’s being honored for 30 years of advocacy.

After Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle”—a scathing look at the unsanitary conditions of Chicago’s meatpacking plants—was published in 1906, the London Times followed up with a review.

“The things described by Mr. Sinclair happened yesterday, are happening today, and will happen tomorrow and the next day, until some Hercules comes to cleanse the filthy stable,” read the article.

Over the past three decades, Darin Detwiler, associate teaching professor at Northeastern, has tried to become that Hercules through his relentless advocacy for food safety.

And this summer, he’ll be recognized for it in a big way.

The International Association for Food Protection (IAFP) will grant Detwiler the 2022 Ewen CD Todd Control of Foodborne Illness Award, which “recognizes an individual for dedicated and exceptional contributions to the reduction of risks of foodborne illness,” at its conference in August.

“It’s a great honor,” Detwiler said of the award. “It’s extremely humbling.”

But Detwiler’s work isn’t about the awards.

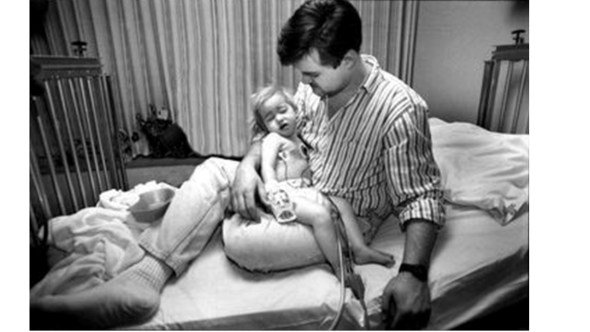

In 1993, his 16-month-old son Riley died of E. coli poisoning during a well-publicized outbreak in ground beef. Riley had never eaten a hamburger, but he got infected at a daycare center from a child whose mother worked at Jack in the Box. During his 2020 TEDxNortheasternU lecture, Detwiler described seeing his young son covered in tubes, being airlifted to a larger hospital, and mistaking an IV bag for a bottle.

Photo Courtesy of Darin Detwiler

“I’ve lived more than half my life in the shadow of those events in 1993,” he said in the TEDx lecture. “The future I imagined for him was taken away.”

Following Riley’s death, a grief-stricken Detwiler became a staunch food safety advocate, representing families who have been affected by foodborne illness. President Bill Clinton called Detwiler from Air Force One, and Detwiler later appeared in a televised town meeting with him. He appeared on Good Morning America, and the secretary of agriculture invited him to advocate for requiring that raw meat be labeled with a warning to wash hands and cook thoroughly—much to the meat industry’s chagrin.

From there, his work has spanned countless stakeholder committee memberships, speaking engagements, conference panels, and advisorships. One of Detwiler’s biggest goals was creating awareness: He had learned about E. coli on his son’s deathbed and wanted to “make E. coli a household name.” In doing so, he also made Riley and himself into food safety celebrities—pictures of Riley hang at offices at the FDA.

After Riley’s death, Detwiler, initially a nuclear engineer on a submarine in the Navy, got degrees in history, education, and law, and taught high school and middle school math, history, and science for 16 years. On the 20th anniversary of the E. coli outbreak, his students found out about his background when they were discussing foodborne illness. A student asked a question that changed Detwiler’s life: “‘If this is still a problem now, why are you just a history teacher?'”

“I had to do a lot of thinking about that,” Detwiler said.

He left his career a few months later and took a job at Northeastern, where he worked his way from adjunct instructor to assistant dean in the College of Professional Studies, and continued his advocacy. Last year, he left the deanship and now focuses on teaching remotely from his home in California.

His courses range from entrepreneurship, to the global economics of food, to corporate responsibility, but at the center of it all is food safety. His focus is on inspiring his students, whom Detwiler knows will go on to work in a variety of industries and could impact whether corporations prioritize public health over profit.

“No matter what area my students focus on, everyone eats,” he said. “The better I can train, inform, and educate the future, to me, that’s where I have the biggest responsibility and the biggest potential impact.”

This work is as important as ever. Recent recalls of Abbott baby formula, Jif peanut butter, and organic strawberries have made their way into the mainstream media, reminding Detwiler that the issues that led to the 1993 E. coli outbreak are still prevalent.

“It’s 30 years later, and the same Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates from back then—48 million Americans are estimated to get sick every year from a foodborne pathogen, some 128,000 are hospitalized, and some 3,000 Americans die every year—haven’t changed at all,” he said.

Detwiler finds hope in the potential for new technology to help prevent foodborne illness, including how social media is helping to create more awareness.

Nearly 30 years into his work as an advocate, he’s not slowing down any time soon. In fact, Detwiler, far from thinking of himself as Hercules, considers the award an invitation to do more, not only now but over the next 20 years.

“There’s always going to be foodborne pathogens,” he said. “But we can do better.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.