Here’s what you should know about the mysterious, severe hepatitis reported in over 100 U.S. children

Last month, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a cluster of nine young children in Alabama—all previously healthy and none with any underlying conditions—who came down with serious liver inflammation, also known as hepatitis.

Two of the nine patients needed liver transplants, and three even developed liver failure. All of the children have since recovered or are in recovery, but the cause of their puzzling infections remains a mystery to those in the medical community, who are scrambling to try to identify the source while more potential cases get reported.

Brandon Dionne, a clinical professor in the Department of Pharmacy and Health Systems Sciences at the Bouvé College of Health Sciences at Northeastern. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

As of last week, 100-plus cases of severe hepatitis of unknown origin in young children in the United States were under investigation by the CDC. Many more infections were reported abroad. With the news of the possible uptick in cases, infectious disease experts, including one at Northeastern University, are recommending that parents and guardians take some of the daily precautions they have taken during the coronavirus pandemic: wash your hands, do not touch your eyes, mouth, or nose, and stay home if you feel sick.

“This is still a relatively new thing, but it’s worrisome, because it can lead to pretty severe illness in children,” says Brandon Dionne, a clinical professor in the Department of Pharmacy and Health Systems Sciences at the Bouvé College of Health Sciences at Northeastern. “The big thing is for parents and guardians to watch out for the symptoms of hepatitis in children and act quickly.”

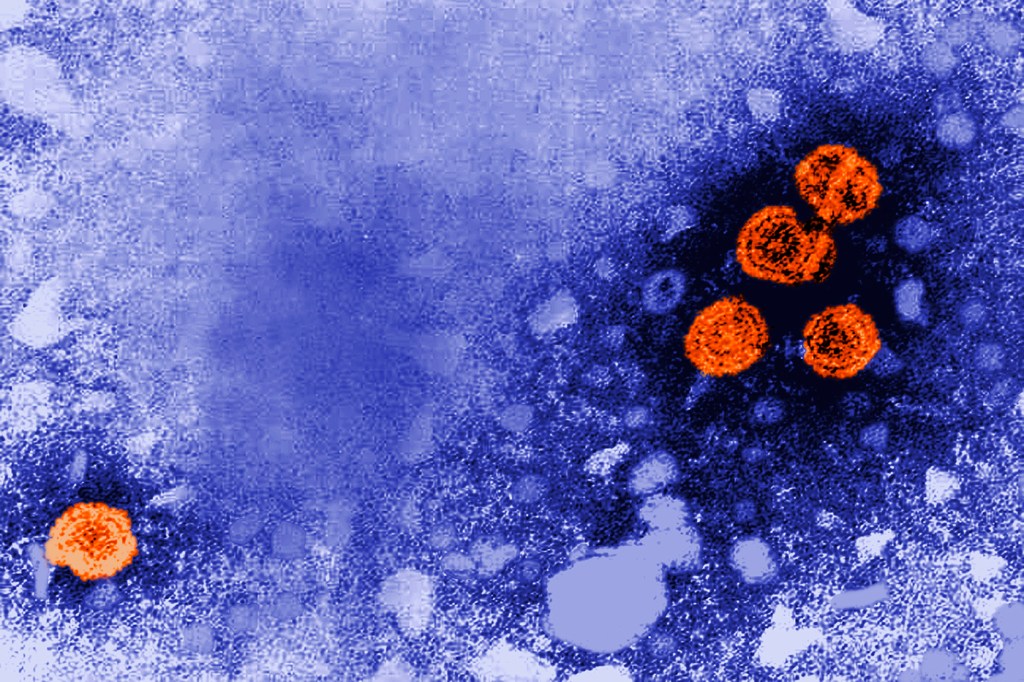

A common theme in many of the pediatric hepatitis patients around the U.S. and the world is that they are also being diagnosed with adenovirus, a common virus that typically causes mouth colds, flu-like symptoms, and stomach problems. It is not normally associated with serious liver inflammation in otherwise healthy children, which is a concern, Dionne notes.

Dionne, a clinical pharmacist whose expertise is in antimicrobial stewardship and the treatment and prevention of infectious diseases, works with mostly adult patients at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. The professor says he has seen plenty of adenovirus cases among adults, who experience largely minor respiratory symptoms.

“It’s usually a seasonal respiratory illness that’s responsible for common cold-like symptoms,” Dionne explains.

The specific strain of adenovirus identified in many of the pediatric hepatitis cases recently is Adenovirus type 41, which has previously only been associated with hepatitis in immunocompromised patients, according to Dionne. But even then, it is still incredibly rare.

“This is the first time they’ve seen it in immunocompetent patients,” he explains. “It’s certainly something that we should be keeping an eye on.”

In a media briefing on May 6, Dr. Jay Butler, deputy director for infectious diseases at the CDC, said the agency was investigating 109 children with acute hepatitis in 25 states and territories reported over the past seven months. More than 90% of the patients were hospitalized. Approximately 14% received liver transplants and more than half had a confirmed adenovirus infection.

The updated number of cases and deaths came after the federal government issued a nationwide health alert asking physicians to be on the lookout for and report any suspected cases of liver inflammation with unknown origin.

Butler noted the CDC is also aware of pediatric hepatitis cases of unknown cause recently discovered in other countries.

“We are working closely with public health officials around the world to understand what they are learning,” he said, noting that based on initial investigations, some of the common causes of viral hepatitis—including Hepatitis A, B, C, Delta and E—have been considered and tested but not found in any of the reported patients.

At this time, the CDC says it believes adenovirus may be the cause for some of these cases, but other potential environmental and situational factors are under investigation. Adenovirus 41 is not usually known for causing such severe liver issues in non-immunocompromised children, and no known epidemiological link among these patients has been found.

Amid rumors circulating online about the potential source of the severe pediatric hepatitis cases, Butler made sure to emphasize that the coronavirus vaccine is not the cause. None of the nine children in Alabama had COVID-19 infections while they were hospitalized with hepatitis, and none had a documented history of coronavirus. Additionally, none had received the COVID-19 vaccine before they went to the hospital.

Beyond the mystery surrounding the cause of these hepatitis cases, Dionne recognizes another big question: “If it is in fact Adenovirus 41 that’s the source, then why are we suddenly seeing hepatitis with it?”

“That’s the trickiest part here. If we identify that this is a complication of Adenovirus 41, we still don’t know whether there’s a new variant causing this,” he says. “If this is a new variant, that will be more concerning, because then we will likely see more of these cases. We don’t know that yet.”

As these cases remain under investigation, the CDC notes that it is important to remember that severe hepatitis in children is rare, even with the potential increase in cases publicized last week. Still, the agency, as well as Dionne, are encouraging parents and caregivers to be aware of the symptoms of hepatitis: vomiting, dark urine, light-colored skin, and yellowing of the skin, also known as jaundice.

“If your child is experiencing symptoms, like respiratory illness, keep a close eye on them and watch out for more severe complications. In most cases, though, it will be like the common cold,” Dionne says. “More severe symptoms are an immediate reason to bring them in for medical attention.”

The CDC also recommends that children continue to be up to date on all their vaccinations and that parents and caregivers of young children take the same, everyday actions that the CDC recommends for preventing a number of infections, including washing your hands often, keeping away from people who are sick, covering coughs and sneezes, and avoiding touching your hands, eyes, or mouth.

Additionally, if you do not feel well, stay at home, notes Dionne, who says that some of the current transmission of adenovirus is likely due to people showing up to school or work while sick.

“As much as you can, if your kid isn’t feeling well, try to keep them at home or at day care,” Dionne says. “Don’t send them to school.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.