Does the shape of our neurons define our behavior?

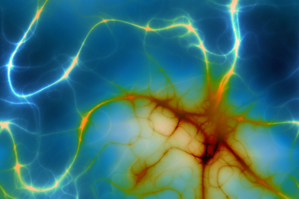

People have often said that the brain is the most complex thing in the universe. Of course, a statement like that spurs heated debate, but it’s still an interesting concept. The human brain consists of 100 billion neurons and several hundred trillion synapses, according to assistant professor of psychology Rebecca Shansky. In her Lab of Neuroanatomy and Behavior, Shansky is studying the structure of neurons and how communication between them, among that complex network, drives behavior.

People have often said that the brain is the most complex thing in the universe. Of course, a statement like that spurs heated debate, but it’s still an interesting concept. The human brain consists of 100 billion neurons and several hundred trillion synapses, according to assistant professor of psychology Rebecca Shansky. In her Lab of Neuroanatomy and Behavior, Shansky is studying the structure of neurons and how communication between them, among that complex network, drives behavior.

“Our long term goal is demonstrate the real functional relevance of structural differences between males and females with specific relevance to fear,” she said. Apparently females are two times as likely to suffer from post traumatic stress disorder than males. Other odd disparities in the way we behave seems to indicate that there may be some interesting differences in the structures of our neurons, which could inform better treatment strategies for behavioral disorders like PTSD. “Even though the symptoms are the same among males and females, the underlying neurobiology may be different,” said Shansky.

She was recently awarded a $275,000 grant from the National Institutes of Health to explore potential differences in the brains of male and female rats. She will look at 100 male and 100 female rates (apparently ridiculously high numbers for animal studies), choose the ones who show extremely high or low levels of fear and examine the neurons known to be involved in fear.

“We’re trying to get a comprehensive profile of resilience and vulnerability,” she said. They will look at things like how many “spines” are sticking off of a vulnerable animal’s neurons compared to a resilient one. They’ll look at the shape of those spines — are they skinny or mushroom-like? — as well as the size of the entire neuron. “We’ll be looking for structural correlates of behavior,” said Shansky.

Apparently only a small percentage of people are susceptible to PTSD — most of us experience something in our lifetime that could cause trauma for one person but not another, such as a car accident or the loss of a loved one. What makes people who do get PTSD special? What makes some vulnerable and others “super resilient”? These are all questions Shansky hopes to answer eventually.

“Everything changes your neurons. The brain is in constant flux,” she said. Thus, an already complicated system is constantly being changed and adapting by our experiences. Perhaps the very shape of our neurons in the first place informs that process.