How to simplify complex supply chains amid unprecedented disruption

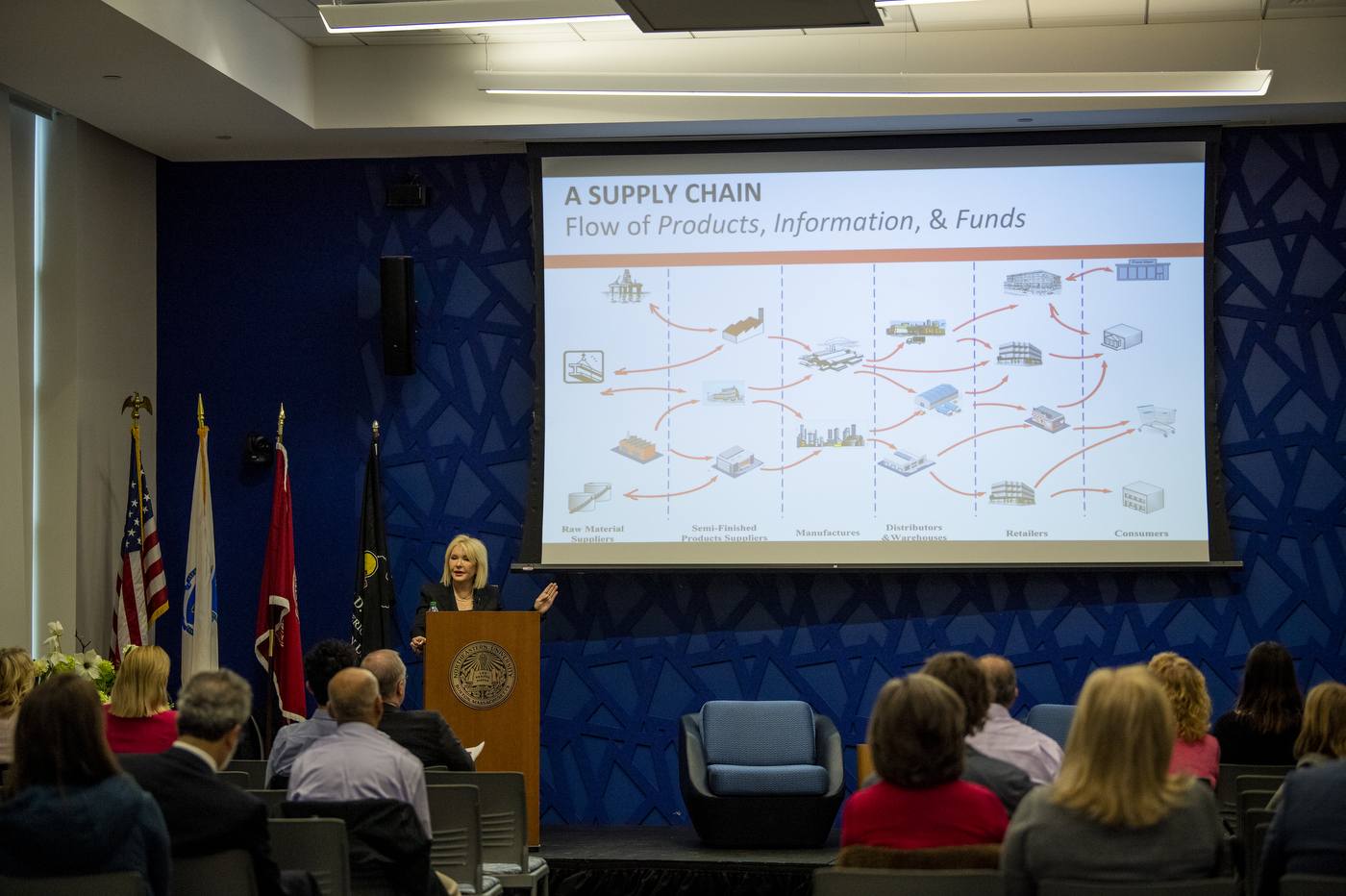

Global supply chains are long, complicated logistical networks that organize the production and distribution of countless products worldwide. They’re how produce from tropical climates arrive at the grocery stories in wintry New England, for example.

But if the COVID-19 pandemic showed businesses anything, it’s that one stoppage along these vast supply chains can propagate across the entire system, leading to critical shortages in everything from food to the raw materials for computer chips used in all sorts of technology, says Nada Sanders, distinguished professor of supply-chain management at Northeastern, who delivered the 58th annual Robert D. Klein Lecture Tuesday on the subject.

“The COVID pandemic has revealed the criticality of global supply chains to everyone—government, business leaders, and the average person,” she said.

The lecture was established in 1964, and is given each year by a member of the teaching faculty who has contributed with distinction to his or her field of study. It was renamed in 1979 in tribute to the late Robert D. Klein, professor of mathematics, chairman of the Faculty Senate Agenda Committee, and vice chairman of the Faculty Senate.

Sanders’ lecture, “Global Supply Chains: Current State, the Future, and Using Collective Intelligence for Redesign,” also highlighted how the ongoing invasion and occupation of Ukraine by Russia has translated into global shortages of wheat and sunflower oil, among other products.

To truly illustrate the precarity of supply chains, Sanders said to look no further than the Boeing aircraft, which has more than three million component parts manufactured in more than 65 countries.

“Think about the fact that each of these components take a different amount of time to make, a different amount of time to ship, and in order to complete the aircraft, all the pieces have to come together at the same time,” she said.

If there is a delay anywhere along the chain, the aircraft cannot be assembled. Such supply chains are, in some ways, so vast that they should not be thought of as linear assembly lines, but complex, dynamic networks. Because of their complexity, “managing and assessing risk is very difficult,” Sanders said.

“I think we call it a chain, but network is a better way to actually see it,” she said. “Most executives say they cannot map their entire chain. Think about that.”

The problem with the way supply chains are organized is that they are optimized for so-called “just-in-time,” or lean, manufacturing. Lean manufacturing is a principle by which business owners aim to reduce the amount of inventory they have sitting around in warehouses, in favor of ordering and shipping products as needed. While cost-saving, the design also means that vendors have less “pipeline inventory” along the chain to absorb the impacts of disruption.

Lean manufacturing works best “if you have this predictable cadence of goods arriving, with vendors close by,” Sanders said.

“But what happens when you have this really complex chain, when things are really spread out—then you end up having problems when you don’t have enough of anything,” Sanders said. “I think that companies have taken lean too far.”

So what’s the answer?

Sanders said it’s to “carry an excess of inventory” for critical items. It’s also important, she added, that companies reduce offshore production in case production shuts down in one particular part of the world—such as it has in Eastern Europe.

And artificial intelligence will be key to managing these supply chains as whole systems, Sanders said. But not just artificial intelligence: Human problem-solving is just as vital. This symbiosis and mutuality was the subject of her book, “The Humachine: Humankind, Machines, and the Future of Enterprise.”

“You need both, and we need to find ways to actually leverage both,” she said. “And that is really the answer to solving this complex problem.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.