To deal with COVID-19, the US should look to countries in Asia and Africa

Contrary to common sense, wealth has played a smaller role in determining a country’s ability to manage the pandemic. Some developing or newly industrialized countries in Asia and Africa are experiencing only one percent or less of the amount of COVID-19 deaths per million population seen in the United States despite having much smaller per capita incomes.

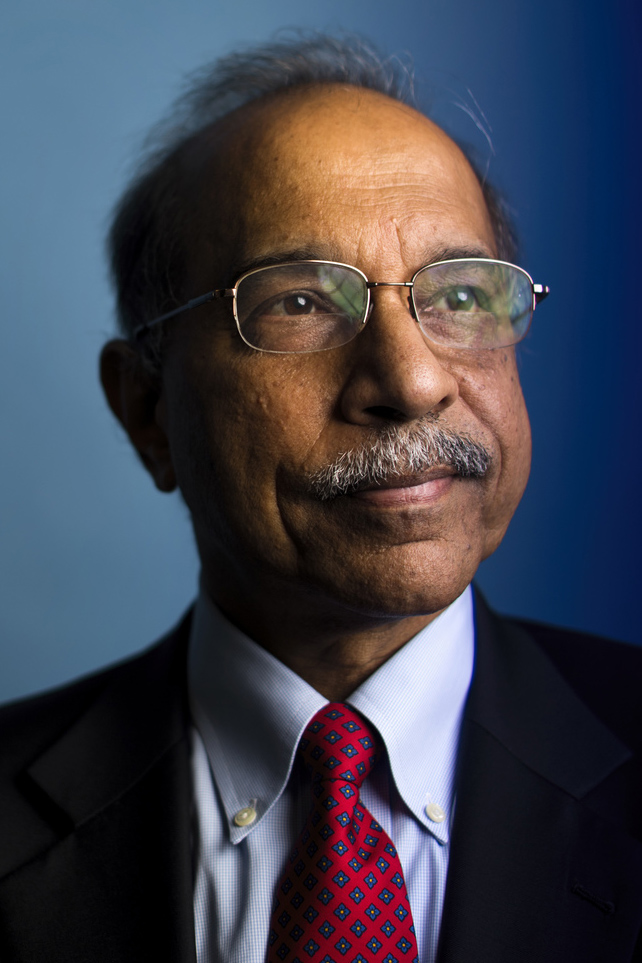

Leaders in contact tracing, rapid testing, and isolation protocols have emerged from countries with economies that are much smaller than that of the U.S. Ravi Ramamurti, university distinguished professor of international business, says the U.S. should take note of them.

This phenomenon—wealthy countries looking toward less affluent countries for solutions—is called reverse innovation.

Ravi Ramamurti is university distinguished professor of international business and director of the Center for Emerging Markets at Northeastern. Photo by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University

“In the last few centuries, we’ve had most innovations travel from developed to developing parts of the world,” says Ramamurti, who is also director of the Center for Emerging Markets at Northeastern. “Now we’re seeing more innovation diffusing in the opposite direction.”

With the help of fifth-year behavioral neuroscience student Jorja Kahn and Northeastern graduates Hugh Shirley and Jamie McGloin, Ramamurti recently launched a website that outlines effective strategies developed around the world that countries could emulate in the fight against COVID-19.

The website is “a place to organize, present and consolidate information,” says Kahn.

“We’re trying to reach out to public health organizations and local leaders and add communication links so we can pool ideas from the sources themselves,” she says.

The website offers the best practices in overall strategy, prevention, testing, contact tracing, isolation and quarantining, treatment and vaccines, and reopening.

Rapid, accurate testing, a strategy public health officials say is necessary to overcome COVID-19, was mastered early on in the pandemic by South Korea where the per capita income is only slightly more than half of the per capita income in the U.S.

As of Tuesday, South Korea had recorded 305 COVID-19 deaths.

The country is credited with pioneering two innovations that have been widely adopted worldwide: drive-in testing and testing booths.

“Drive-in testing is safer because it’s outside, people don’t have to get out of their cars, and it reduces the amount of people in hospitals,” Ramamurti says. “It’s a good way to test a lot of people quickly and cheaply.”

Drive-in testing systems were first put in place in South Korea during the outbreak of MERS, a different respiratory coronavirus, in 2015, says Ramamurti.

Part of the reason some developing countries have handled COVID-19 more successfully is because “they’ve been dealing with epidemics off and on for the last couple years,” says Ramamurti.

To manage testing during COVID-19, South Korea invented a new type of portable facility for dense areas where drive-in testing isn’t possible—a pressurized plastic or glass testing booth that eliminates contact between clinician and patient.

From left, Northeastern graduates Jamie McGloin and Hugh Shirley, and fifth-year behavioral neuroscience student Jorja Kahn. Courtesy photos

The patient and clinician are separated by a window with openings for two rubber sleeves that extend to the patient’s side allowing the clinician to extract a sample from the patient without sharing the same air or coming in contact.

This type of booth has already been adopted by Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which, Ramamurti says, “proves that reverse innovation isn’t just theoretical.”

As for innovations in contact tracing, Ramamurti says Vietnam has a unique and extremely effective technique that traces infected individuals, their contacts and contacts of those contacts, plus isolation protocols to make the tracing worthwhile.

Anyone in Vietnam who tests positive and anyone in contact with someone who tests positive is isolated for two weeks in government facilities, free of charge, and contacts of contacts are required to isolate at home.

Per capita income in the U.S. is nearly 26 times that of Vietnam, and as of Tuesday, Vietnam had recorded 16 COVID-19 deaths.

“I’m hesitant to say which country has the best contact tracing method because of the privacy issues,” says Shirley, one of the Northeastern graduates. “While Vietnam’s effective, it’s very totalitarian.”

Ramamurti says that people have questioned whether these successes can merely be chalked up to different political systems. “But what about South Korea? It’s a democracy,” he says.

Shirely agrees that “while a lot of countries we looked at are communist, a lot of them are democracies, which shows that it isn’t impossible to achieve this in the U.S. with this style of government.”

But if government style isn’t a factor necessarily in determining which emerging markets will have effective COVID-19 procedures, what is?

In addition to the fact that many of these countries have dealt with epidemics in the past, Ramamurti says, “Prevention is much cheaper than curing a disease. These countries have strong public health systems, but they might not have the resources to treat people who are seriously sick, so they have to nip the outbreak in the bud.”

“In the U.S., we start with the assumption that people are going to get sick. We think we have enough doctors and equipment, so we think if people get sick we can fix it,” he says.

But, as McGloin points out, “We’re running thin on that luxury in the U.S.”

As the world prepares for a potential second wave of COVID-19 this fall, will the U.S., still unable to control its initial outbreak, look toward other nations for much-needed solutions?

“Let me put it this way: if we get another outbreak on our shores in the future, the U.S. needs to handle it very differently,” Ramamurti says. “The U.S. should look to countries where it doesn’t normally look to and learn from them.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.