These microbes don’t always play well together, but the combination could cut cost of biofuel

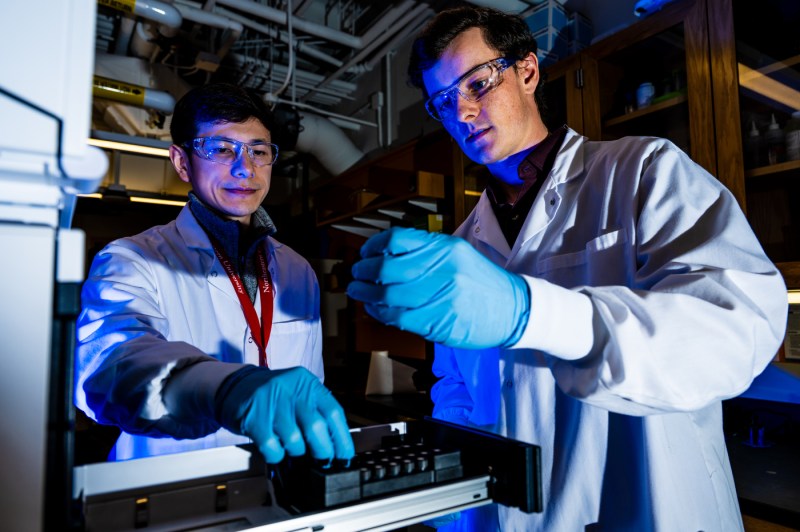

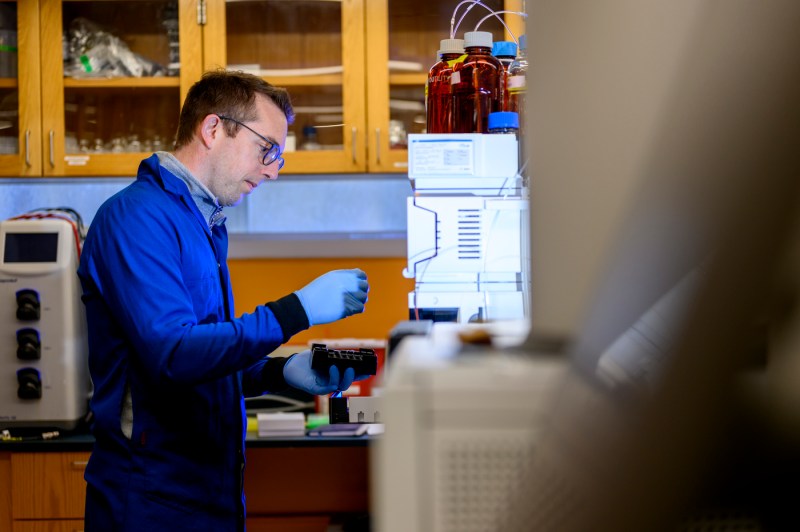

“The core technology we’re working on here can be summed up by asking the question — can it be that two microbes are better than one?” said Northeastern Chemical Engineering Professor Ben Woolston.

It’s well understood in microbiology that aerobic microbes and anaerobic microbes don’t always play nice.

Aerobic microbes thrive in oxygen-rich environments, while anaerobic microbes are just the opposite, preferring those with little to no oxygen at all, explained Ben Woolston, a chemical engineering professor at Northeastern University and principal investigator of the Woolston Lab.

Given their differences, they are regularly placed in two separate single-microbe-type bioreactors, environmentally controlled vessels used to cultivate microbes in the development of products like biofuels and pharmaceuticals.

But researchers out of Woolston Lab are trying to flip that practice on its head in an attempt to bring down the costs of the production of biofuel, save energy, and in turn reduce our reliance on fossil fuels, said Woolston.

They have proposed a novel approach that would allow both an anaerobic microbe and an aerobic microbe to grow together in the same bioreactor.

The research project builds off a key discovery made in Woolston’s lab — if the oxygen levels of a bioreactor are set low enough, there should be no issue for anaerobic microbe and aerobic microbe to share the same reactor.

That discovery was made by 2021 Northeastern graduate Anthony Stohr, who worked at Woolston’s lab as an undergraduate.

“The core technology we’re working on here can be summed up by asking the question — can it be that two microbes are better than one?” said Woolston.

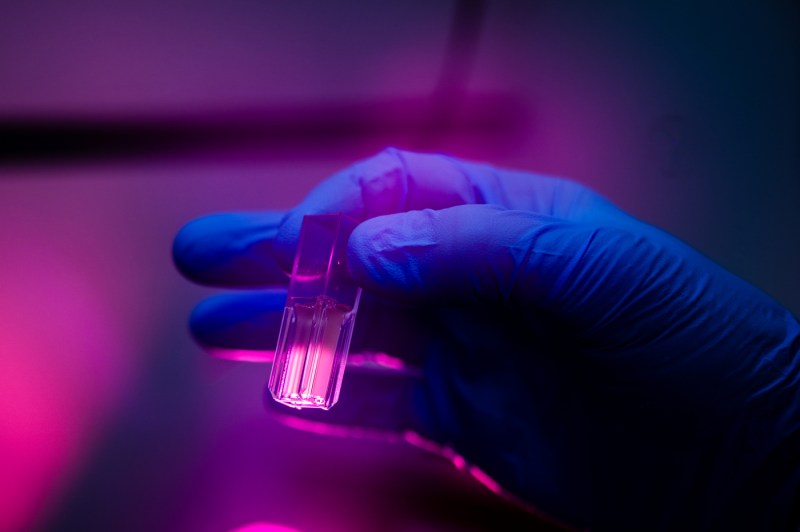

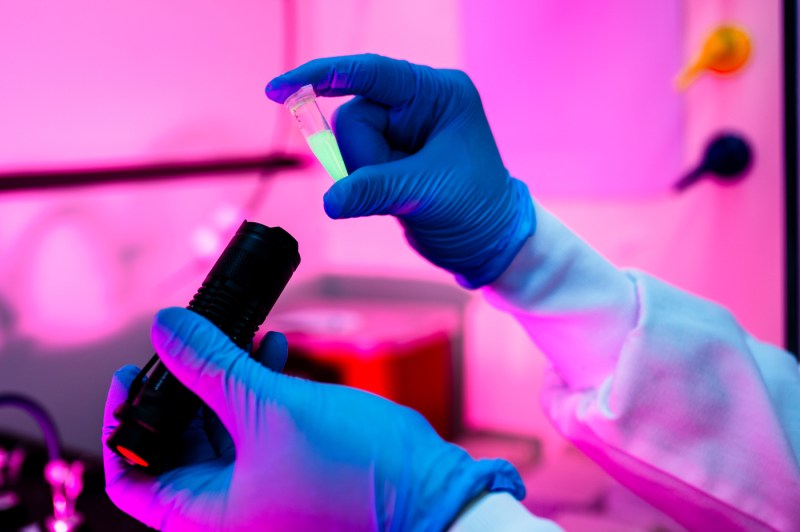

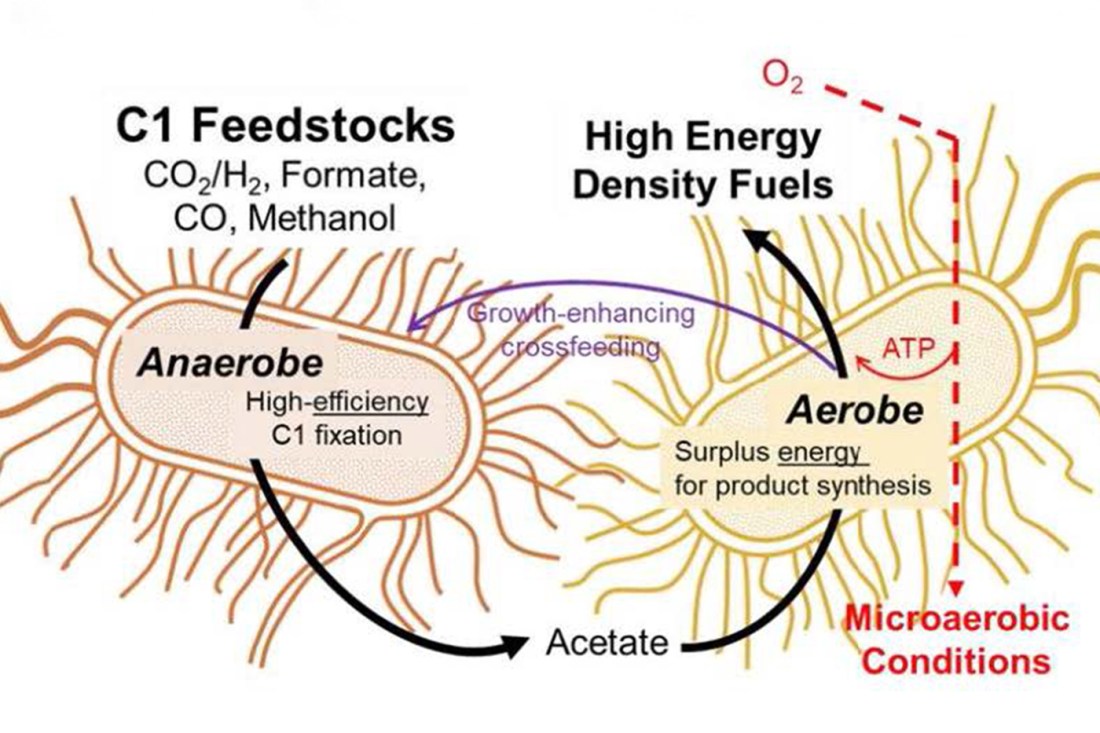

For this project, the researchers are interested in converting C1 feedstocks — one-carbon compounds such as carbon dioxide, formic acid and methanol — into high-energy density fuel that could be used for jets and long-haul ships.

Both aerobic and anaerobic microbes play a key role here.

Although they are slowly moving, anaerobic microbes are efficient and are able to capture large amounts of carbon available in the feedstock. Aerobic microbes, on the other hand, are very fast and are able to capture carbon much faster, but don’t pick up as much, he said.

“The idea with this co-culture is can we put both types of these microbes in the same reactor to get the best of both worlds,” he said.

Here’s how the process would work: First the anaerobic microbe takes the C1 feedstocks and converts it to a C2 feedstock – two carbon compounds such as acetate — that is then sent over to the aerobic microbe, which then converts it directly to high-energy-density fuel, Woolston said.

“It’s a symbiosis you could say,” he said. “You have both microbes working together.”

Editor’s Picks

Traditionally, this would be a two-step process, explained Guanyu Zhou, a doctoral student in Woolston’s lab and one of the lead researchers on the project.

One bioreactor containing the anaerobe would convert the C1 feedstocks into the C2 feedstocks. Then that product would be placed in another bioreactor containing the aerobe microbe to be converted into the high-energy-density fuel.

“It costs a lot of money, so if you can combine these two into one reactor you can save a lot of money,” said Zhou.

William Gasparrini, another doctoral student in Woolston’s lab working on the project, said this new approach would have 90% reduction in oxygen demand compared to the two-bioreactor method.

“This translates to major savings on aeration and cooling costs-typically the largest operating expenses in biofuel production,” he said. “Lower oxygen requirements also improve safety when working with flammable gases like H2 and CO, since we can operate with non-flammable gas mixtures.”

Over the next few months, the team will be optimizing the bioreactor to determine the exact levels of oxygen they’ll need to make this work.

In current experiments, the team has been feeding the bioreactor with just 5% of air, which is composed mostly of nitrogen and just small amounts of oxygen, which is consumed by the aerobe almost instantaneously, said Gasparrini.

While the team still has some work to do, they said they are close to hitting the finish line on the project, he said.

“We’re actually really really close with this,” he said. “It’s been a five-year project making these small incremental improvements on the system, but we think we have a fuel now and now we’re waiting on some analytics to come back from a reactor we ran last week to show that we’re producing our target compound from our carbon substrate.”

The lab recently received an ARPA-E — Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy — IGNIITE award from the U.S. Department of Energy, funding that the U.S government said it gives “to support early-career innovators seeking to convert disruptive and unconventional ideas into impactful new technologies across the full spectrum of energy.”

The researchers’ multi-years long collaboration with ARPA-E will be essential to bring this research project to commercialization, Woolston said.

By the project’s end, the team will have to produce a go-to-market plan and a techno-economic analysis of the project, a type of report that investors can read to understand the project’s economic viability.

“Once we’ve got the science developed, we have to figure out as part of this award how we go forward in terms of future investments,” Woolston said.