Three Northeastern professors want to study how the way you walk impacts your health and your city

With WalkSensePlace, researchers will study the “conversation between our feet and the environment” to better understand how to design walkable cities and the relation between walking and health.

Walking is one of the simplest modes of transportation on the planet. Almost everyone does it, and the American Heart Association says it’s key to a healthy lifestyle.

How much time, however, do you spend thinking about your feet?

These researchers at Northeastern University want you to think about your feet, and about walking, and how the way you connect to the ground in a day-to-day way affects the health of both you and the environment you move through.

Using advanced insole sensors designed by a company called Stapp One, the researchers hope to study everything from the human gait to urban planning and design. Crucially, all these experiments can be done outside the laboratory and in the real world.

Their first task is to train the sensors to distinguish between the different kinds of terrain we walk on, like solid pavement, slightly springy grass or slippery ice and snow. Amy Lu, associate professor of communication studies and public health and health sciences, says the project “is almost creating a kind of conversation between our feet and the environment.”

Sensing the places we walk

The project, called WalkSensePlace, is still taking its first steps. For Kristian Kloeckl, an associate professor of design and architecture, he hopes that the study will reveal the kinds of spaces people gravitate to when they walk and inform our understanding of a walkable city.

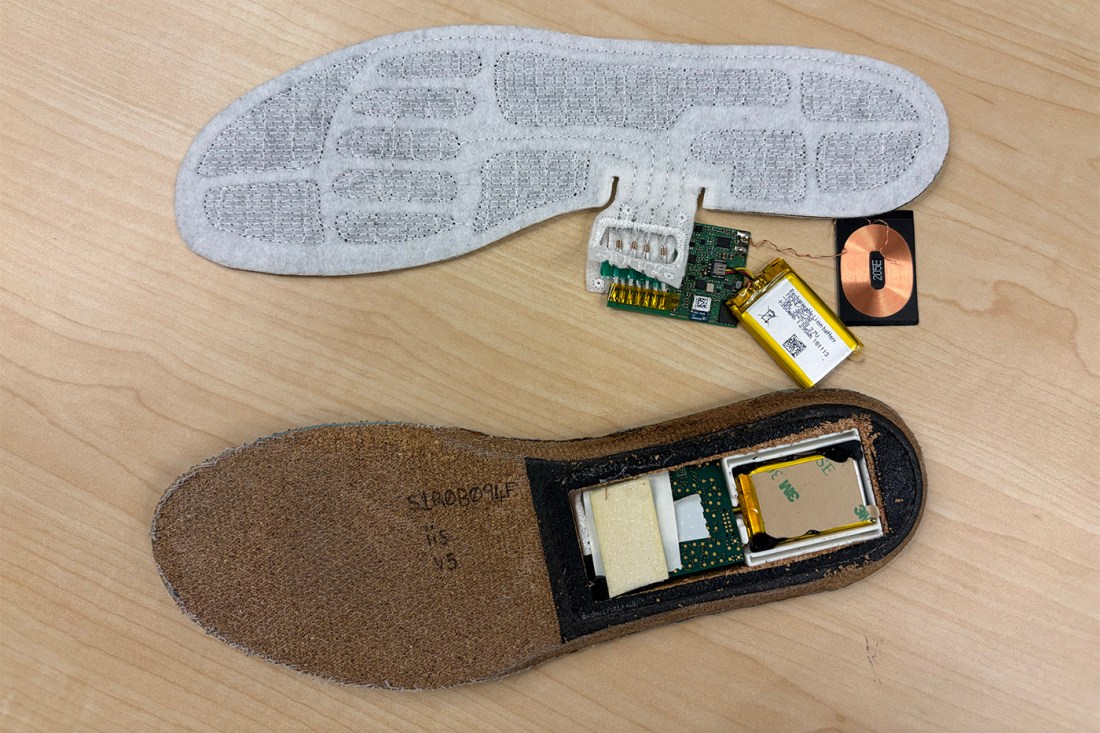

Kloeckl and Stapp One’s founder and CEO, Peter Krimmer, met at a showcase of Austrian entrepreneurs. As soon as Kloeckl saw the sensors, he knew they were unique. Previous insole-style sensors, Kloeckl says, had large battery packs attached to them, or required the wearer to walk in a laboratory setting, hooked up to machines.

The Stapp One insoles, however, are only as thick as a regular shoe insole, with batteries built into the sole itself that can be wirelessly charged after days of wear. Also built hinto the insoles are 12 discrete sensors that measure the distribution of weight across the foot. When Kloeckl pushes down on the insoles, heat maps are generated on the mobile phone display, showing where the pressure is highest.

Another graph shows how weight moves from one foot to the other, and an accelerometer can even gauge how fast the foot moves or detect when a fall occurs.

With such a small form factor, wearers of the insoles can forget they’re part of an experiment, something that’s next to impossible with the older sensors, according to Kloeckl.

The ground we walk on

Using the data collected by the insoles, Kloeckl and his team, which includes Northeastern students on internal co-op programs, are training a machine learning algorithm to connect the variability between the insoles’ 12 sensors and the kinds of terrain on which people walk.

When combined with geographic information system (GIS) data, the WalkSensePlace team will be able to compare information about the ground conditions stored in digital maps with the in-person experience of human walkers, based on their actual steps.

Where city infrastructure encourages or allows people to walk, Kloeckl says, “is based on clear deliberations and decisions that are made in the processes of planning our cities.” Kloeckl notes, however, that events like inclement weather, construction or simply ad-hoc choice and preference can change the actual paths we take when walking.

This project “will actually provide very unique and individualized data points about walking for different people in different environments,” Lu says.

Both Lu and Kloeckl point to a third Northeastern professor as being key in designing the experiment — Eric Folmar, associate clinical professor of physical therapy, movement and rehabilitative sciences.

Folmar, who says he often works with dancers, likens the foot to a tripod with one point at the heel, one under the little toe and one under the big toe. How and when those points make contact, and the distribution of pressure between them and across the foot, can tell a trained professional like Folmar a lot about how a person walks and the tension they might carry elsewhere.

The same person, walking on different kinds of ground, presents “different pressure mapping,” Krimmer says. He began designing the Stapp One insoles because he was experiencing chronic back pain. He describes the human body like a building: “If something is wrong with the foundation, the roof won’t be stable.” Similarly, if you have shoulder problems, “you can see everything down in the foot,” he says.

Editor’s Picks

Folmar agrees with this, calling the principle the kinetic chain. “You can’t move one thing without creating something at the next joint up or the next joint down,” he says, describing the principle like a “more complicated version” of Dem Bones, the children’s song about the human skeleton.

In that way, the feet can either cause or show signs of downstream issues, like neck pain or Krimmer’s back pain.

Lu hopes to help people reconsider how they travel through the world. “When we talk about lifestyle changes,” she says, it involves “primarily a change of mindset,” leaning into simple activities instead of remaining sedentary — like walking instead of driving.

Folmar says he was hesitant to take on a new project but is now excited by its potential. “I don’t know where it’s going to go in the end. We’re kind of taking three different worlds and making this come together,” he says.

In the short term, Kloeckl says that he’s been glad to see his early student participants deciding to go on walks instead of staring at computer screens all day.