African cinema opens new ways of seeing a vibrant continent

For many students, Tiffany Bailey’s African film class at Northeastern is their first exposure to cinema from the continent. She hopes it can provide “an undoing of stereotypes.”

One of the world’s largest continents is also one of its least seen, at least in the U.S.

In Hollywood, Africa has long been a sore spot for an industry that has tremendous power to shape the way people see the world. In the entertainment that Americans consume, Africa is rarely depicted except as one massive savannah or an underdeveloped, war- and disease-stricken place. Tiffany Bailey wants to correct that.

Through her new African film course at Northeastern University, Bailey, a postdoctoral research fellow, is giving students a chance to get a fuller story of the many parts of the continent, as told by Africans.

“People can maybe admit that they don’t know a lot about Africa, but there are many images of Africa we can conjure,” Bailey said. “People think of animals, ‘The Lion King.’ Africa is very present in our cultural mindset, but from a Western perspective.”

Early Hollywood’s image of Africa as one massive slice of untamed wilderness, a “dark continent,” has changed, Bailey acknowledged. The American film industry has made strides to embrace international cinema, but its lens is still narrow when it comes to Africa and its many film cultures, she added.

Bailey’s course gives students a wide view of an admittedly broad spectrum of film that spans countries, decades and genres. Over the course of the semester, Bailey works her way through 16 films produced in countries across Africa, from Senegal and Chad to Nigeria and Kenya.

“We do a few weeks just on Senegalese films, and that could be the whole course,” Bailey said. “Toward the end, I have a few films only by women directors. That could be a whole course. But my goal was to get students to see as many films from the continent as possible because many have seen zero or one from Africa.”

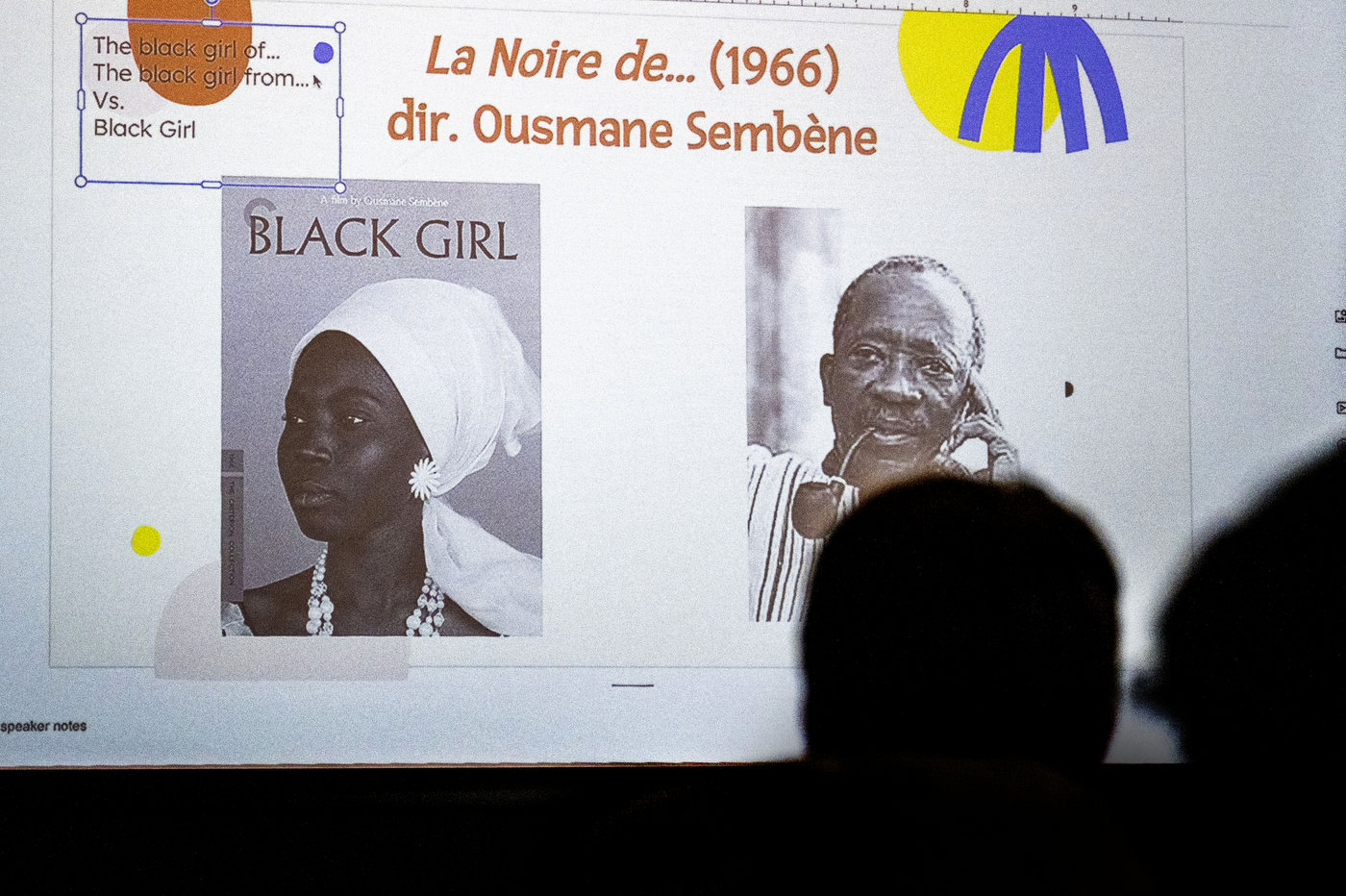

Starting with “Black Girl” (“La Noire De…”), Senegalese director Ousmane Sambène’s 1966 drama that put sub-Saharan African film on the map, Bailey traces a path through African history writ large, not just movie history. The films in her class examine the lasting effects of colonialism, migration, war and death, while also highlighting life and opportunity.

“I don’t think I should only be teaching film,” Bailey said. “If this is going to be their one humanities course about Africa, I feel like I have a responsibility to also teach some of the history.”

Most of her students come into the class having never seen an African film. Their only on-screen idea of the continent is what they’ve seen in American media, which sits somewhere on the other side of reality, said Tarii Collins, a fourth-year communications and media and screen studies student.

“I think it’s portrayed as impoverished,” Collins said. “It’s kind of exoticized to a certain extent. It’s kind of this imbalance.”

For students like Sloan Hinlon, who is studying business and law, films like Sembène’s “Faat Kiné” offer a welcome corrective to that narrative.

“It shows this woman from Senegal who, in a post-colonial era, is able to build herself up and be an entrepreneur and be very successful,” Hinlon said. “That’s a great story to see.”

Editor’s Picks

Beyond watching films, Bailey has designed the course to get students out into the world where the images and ideas they’ve seen on screen come to life. After watching Mati Diop’s “Dahomey,” a documentary about how artifacts were returned to Benin from French museums, they go to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts to see African art and artifacts in a new light.

She also created a pen pal assignment in collaboration with a professor at Nigeria’s Redeemer’s University. Bailey’s students exchange correspondence with Nigerian students, creating cross-cultural discourse about certain films screened in both classes.

“I talked about the diversity of films, but I thought maybe there’s a way I can get students diverse perspectives in real life, not just from consuming something else but personal connections,” Bailey said.

Bailey’s class comes at an opportune time for African film, both inside and outside the continent.

Streaming companies like Netflix have turned to international entertainment to expand their libraries and appeal to global audiences. “Breath of Life,” a 2023 Nigerian drama produced by Amazon, and Netflix’s South African spy thriller “Queen Sono” and reality series “Young, Famous and African” are part of a new wave of globally accessible African entertainment.

But the continent also has its own burgeoning film industries. Over the last 20 years, Nollywood, Nigeria’s entertainment industry, has become the second-most prolific film industry in the world, behind India’s Bollywood, according to the U.S. International Trade Administration.

Bailey said this is just the beginning of Africa’s big screen moment, one that could break down stereotypes about the continent, its people and cultures. She hopes her class can help in its own way.

“I hope this class is an undoing of stereotypes about Africa, an unlearning of what we’ve been taught about Africa,” Bailey said. “In teaching the humanities, I hope I am contributing to making more involved and knowledgeable citizens of the world.”