How a Brazilian ‘mystery’ oil spill traveled over 5,000 miles to the sands of Palm Beach, Florida

Northeastern University research has made a positive identification between an oil spill in Brazil and oil-contaminated plastic trash that washed ashore in Palm Beach, Florida, riding the Atlantic Gulf Stream.

In 2019, Brazil experienced the largest oil spill in its history, affecting nearly 1,800 miles of coastline. No one knew its origin.

The story doesn’t end there. A year later, Florida beach cleanup crews started finding plastic trash contaminated with oil. New research from Northeastern University has made a positive link between the two events: The oil that stained Brazilian waters black in 2019 was the same oil that polluted Florida in 2020, more than 5,000 miles away.

The mystery oil spill

First, what caused all that oil to be released in Brazil?

Bryan James, an assistant professor of chemical engineering, suggests that the most likely theory points to the SS Rio Grande, a German supply ship and blockade runner sunk by American vessels in 1944, off the coast of Brazil.

Many sunken ships, James explains, are “ticking timebombs” as their holds rust over the years. Eventually, their tanks rupture, releasing all that oil.

The connection to the Rio Grande, James continues, was made because of other debris washing ashore — notably large rubber bales identified as coming from the German blockade runner. These bales have appeared on beaches from Belize and Brazil to Florida and Texas.

They don’t know for sure if the oil is also from the Rio Grande, because “nobody’s gone and tapped that ship and collected a sample of oil” for comparison, he says. However, the distribution of rubber bales, along with the oil and contaminated plastic, suggests a strong link.

The Rio Grande, and ships like it, remain inaccessible due to the logistics involved in reaching them. For example, the Rio Grande lies at a depth of over 5,700 meters, or 3.5 miles.

Friends of Palm Beach

Diane Buhler was an investment banker who loved scuba diving on her vacations. After losing friends in the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, she sought a radical change. Eventually, she settled in Palm Beach, Florida. While she already loved its coral reefs and marine life, she started walking the beaches, and paying closer attention to them, as a resident.

What she discovered was shocking — thousands of pounds of trash washed ashore along eight miles of beach.

Buhler turned that shock into action, launching the nonprofit Friends of Palm Beach in 2013. The group employs homeless individuals to remove trash from the area, operating five days a week, year-round, she says. Palm Beach, at Florida’s easternmost point, catches much of the debris carried northward by the Atlantic Ocean’s Gulf Stream current.

In 2025, she reports they removed about 29,000 pounds of waste. The previous year, the figure was 34,000 pounds.

Her crew is so familiar with the area and its debris that they came up with a categorization system to track what they find, including “about 750 pieces of medical waste per year,” according to data they have collected.

Knowing the beach as well as they do, and the typical materials that wash ashore, Buhler says that her crew is tuned in to anomalies — like large rubber bales or plastic bottles covered in oil.

Editor’s Picks

Tracking an environmental threat

Oil spills endanger humans and damage the environment, James explains, releasing carcinogenic compounds and others that “have a negative human health impact” and cause marine ecotoxicity. “Oil can become entrained in the water column and cause adverse effects to other marine life, too, so it can disrupt fisheries,” he adds.

James and Buhler connected via social media when the Friends of Palm Beach posted about finding strange oil-covered bottles.

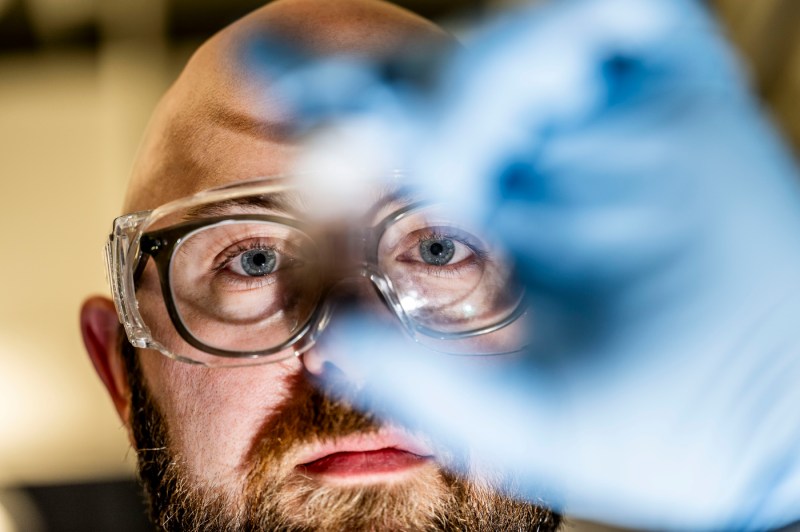

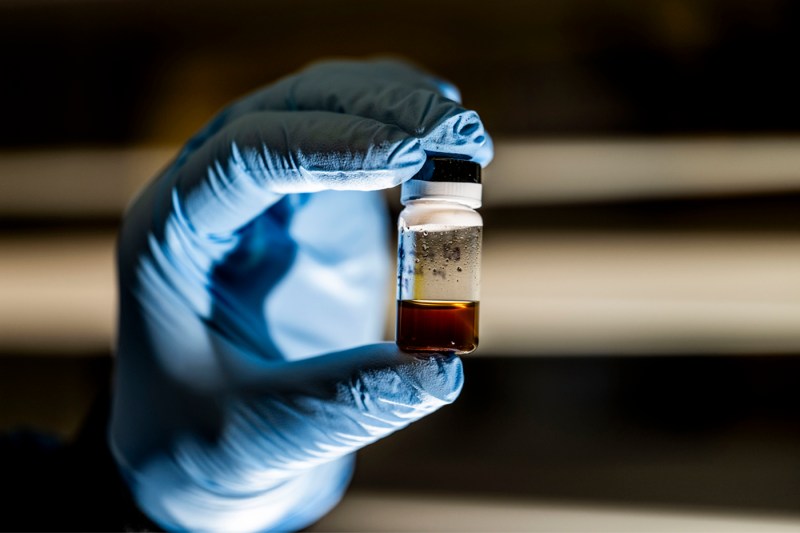

They linked the oil in Brazil to the oil in Palm Beach through a process James likens to fingerprinting. “Each oil has its own, specific chemical fingerprints we call biomarkers,” he explains, “the remnants of the biomass that ends up, over thousands of years, being turned into oil.”

The biomarkers are identified by combusting a sample of oil, then diluting the residue with chemical solvents. The mixture is analyzed by a device called a gas chromatograph, creating a map of the biomarkers. If two samples’ maps match, they originate from the same source.

The oil on the plastic trash in Palm Beach matched the Brazilian oil.

One ocean

James notes that the plastic trash’s natural buoyancy helped spread the oil from Brazil. Scientists have long known that debris can travel around the globe, riding ocean currents, and Buhler says she regularly finds plastic waste from as far as West Africa, 4,000 miles away.

This Florida study provides the first definitive evidence that an oil spill can travel, through plastic debris, over such a distance.

James emphasizes that this research urges us to rethink how we view the oceans. They might be called the Atlantic, Pacific, or Indian, but they’re really “one ocean,” he says.

Even minor spills or pollutants “can impact those far away. We have this responsibility not just to, say, our local community, but globally,” he concludes.