They dug in and came up with an award-winning geothermal plan that is full of ‘holes’

Northeastern students win big in a Department of Energy geothermal energy contest

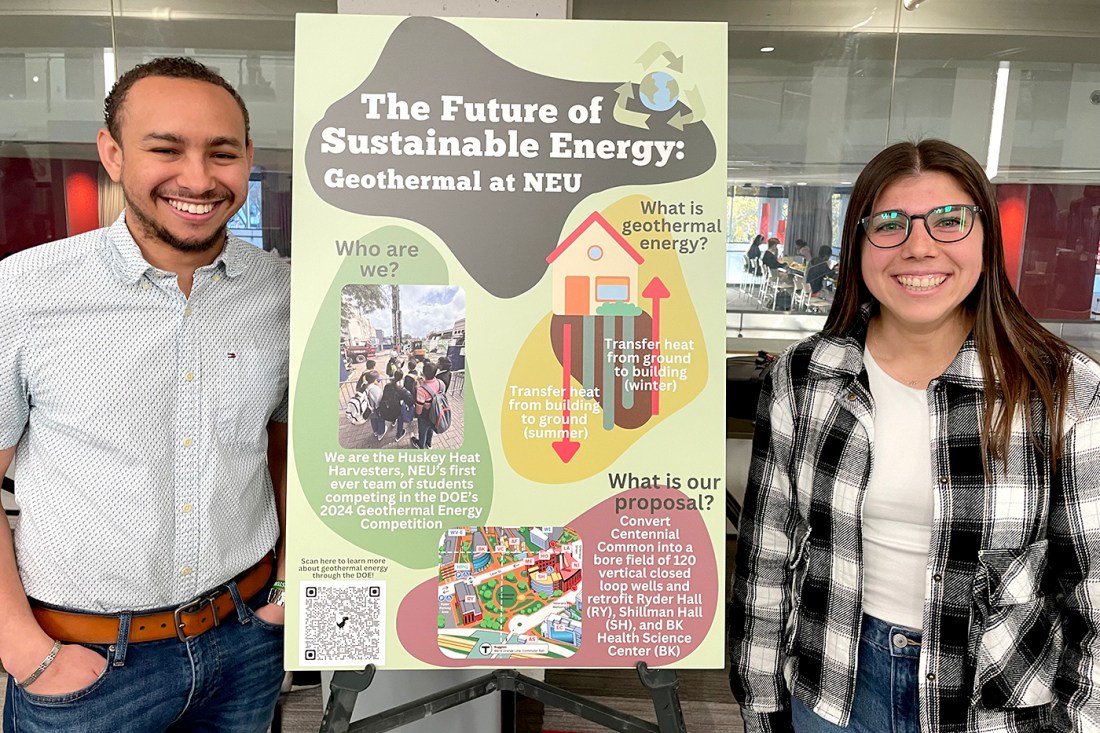

Imagine boring 120 holes, each more than 900 feet deep, under the grassy expanse of Centennial Common on Northeastern University’s Boston campus to release geothermal energy for heating and cooling.

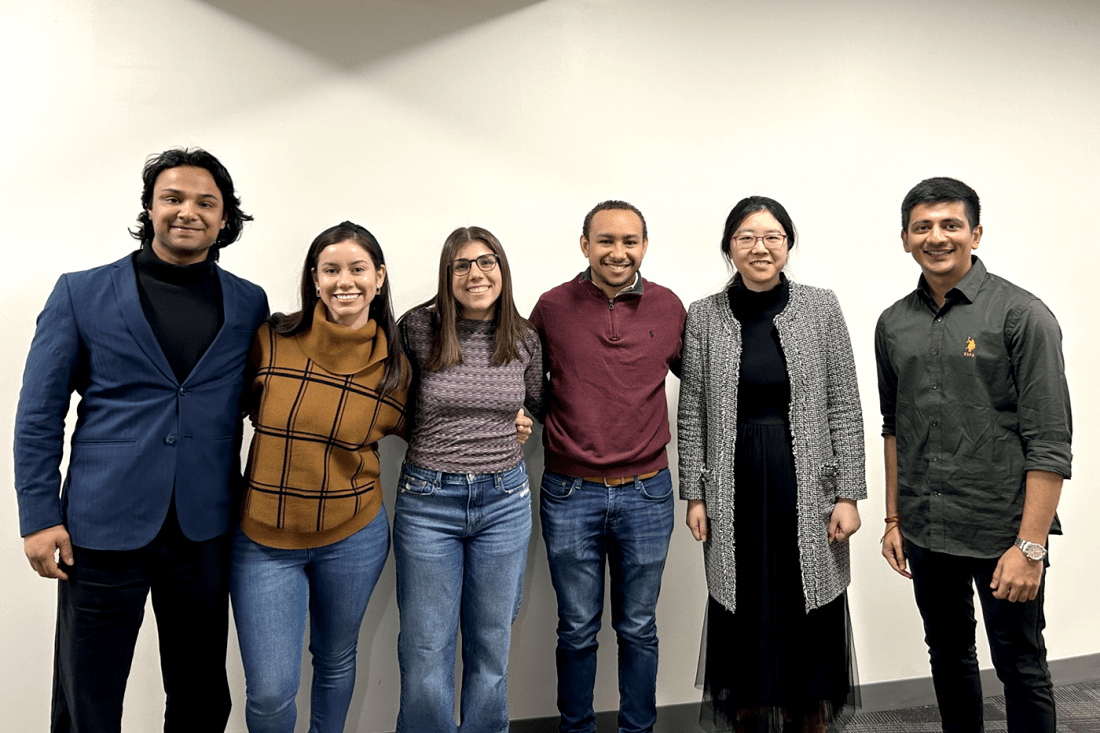

A group of students from Northeastern called the Husky Heat Harvesters drafted a plan to do just that, and won a U.S. Department of Energy collegiate competition for their effort.

Thirty-three teams from 25 U.S. colleges and universities competed in the Geothermal Collegiate Competition, sponsored by the DOE.

The Husky Heat Harvesters took first place and a $10,000 prize in the technical track by developing a project to assess a community’s energy needs and designing a theoretical geothermal heating and cooling system for that community.

“We decided what better choice than our Boston campus because there are already geothermal efforts going on here and also decarbonization efforts going on in the city of Boston,” said Emma Ortiz, a second-year master’s degree student in mechanical engineering and leader of the Husky Heat Harvesters team.

Team members worked with university staff and outside contractors to understand the geothermal features being planned for Northeastern’s Roux Institute in Portland, Maine, and the new multipurpose athletics and recreational complex that will replace Matthews Arena in Boston.

“Luckily, they were doing the test drilling for the Matthews Arena, so we got to see an actual geothermal well being drilled, and we got to ask questions about that,” Ortiz said.

The team then came up with its own plans to heat and cool Ryder Hall, Shillman Hall and Behrakis Health Sciences Center with a pegboard of pipes under Centennial Common.

“The idea was to replace some of the energy we currently get from the steam plant,” which needs updating and is based on fossil fuels, said Chaz Garraway, a Husky Heat Harvester and second-year master’s degree student in Northeastern’s climate science and engineering program.

It’s about transitioning “to a new energy source that’s more renewable, more reliable and more sustainable,” Ortiz said.

Geothermal energy works by using water to transfer heat from the ground to a building in winter and extracting the excess building heat and depositing it in the ground for later use in the summer, she said.

“If you dig or drill deep enough, that temperature is going to be constant,” Ortiz said.

“The technical term for this type of geothermal energy is actually ‘geothermal exchange,’” says Jacob Glickel, director of sustainability operations at Northeastern.

“You kind of use the ground as a battery to store thermal energy for when you need it,” he said.

“This was a really great project,” said Glickel, who connected the Husky Heat Harvesters with internal capital project teams and consultants for Northeastern’s geothermal endeavors.

“Emma and her team were fun to work with. They really listened to our feedback,” and used what they learned to push ideas forward, he said.

While the Centennial Common project is theoretical, Husky Heat Harvesters said in a video submitted to the DOE — which tied for honorable mention in the video category — that they could see where it could be part of an exchange of energy, tying the campus together.

It’s a goal shared by people like Andrew Iliff of HEET, a Boston-based nonprofit advocate of thermal energy.

Editor’s Picks

During a second video the Husky Heat Harvesters put together for a stakeholders event celebrating their win Oct. 30, Iliff said geothermal networks will bring communities together to share energy and ideas, “to come together as buildings but also as people.”

The Northeastern team did its best to spread the word about the possibilities of geothermal energy with presentations on campus and at a Boston public school.

Getting the community involved in the 2024 Geothermal Collegiate Competition contributed to the Husky Heat Harvesters’ success, Garraway said. Before the winners were announced in April of this year, “I don’t think anyone thought we would win on our first try,” he said.

The team hopes to pay its winning forward, Ortiz said.

In addition to the $10,000, which was dispersed among Husky Heat Harvesters, there are also funds left over from $9,000 they were given to host the stakeholders’ event.

“We’re in discussions about what we want to do with the rest of the money,” Ortiz said. “We’re leaning toward a donation to a community or school or sponsoring a field trip. We want to continue a conversation about promoting sustainable practices and sustainable energy.”