Biodegradable technology can dissolve into harmful microplastics, Northeastern research uncovers

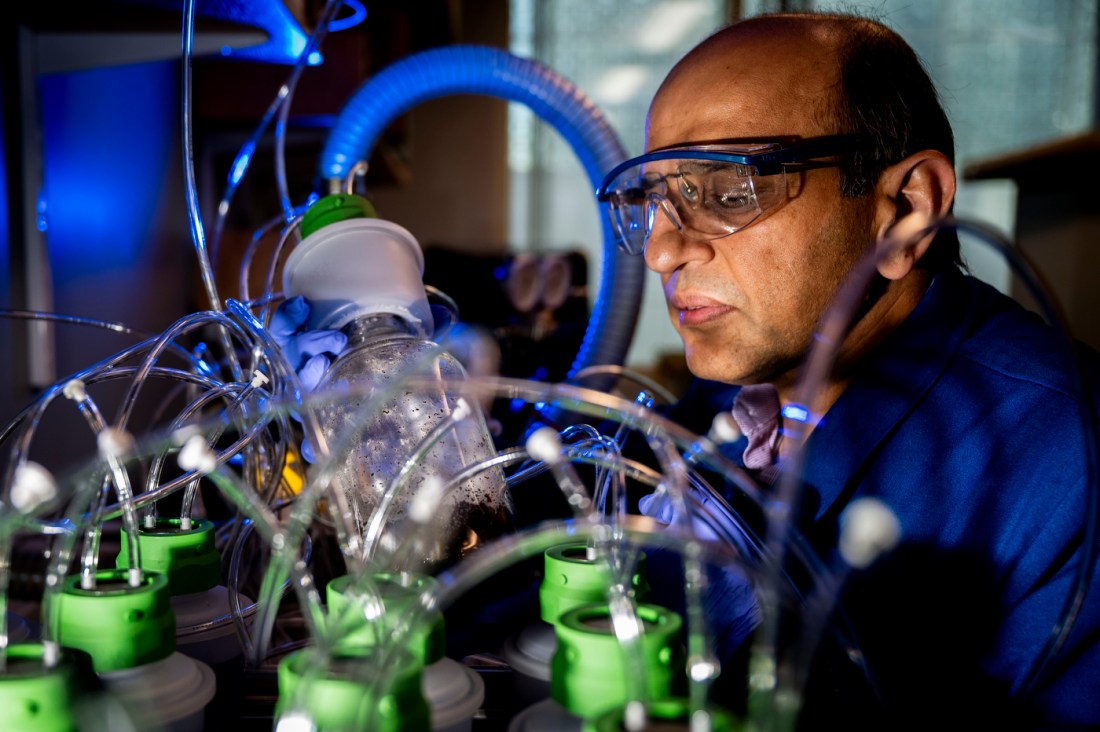

Ravinder Dahiya and researchers in his lab are studying electronic degradation and its damaging impact on the environment.

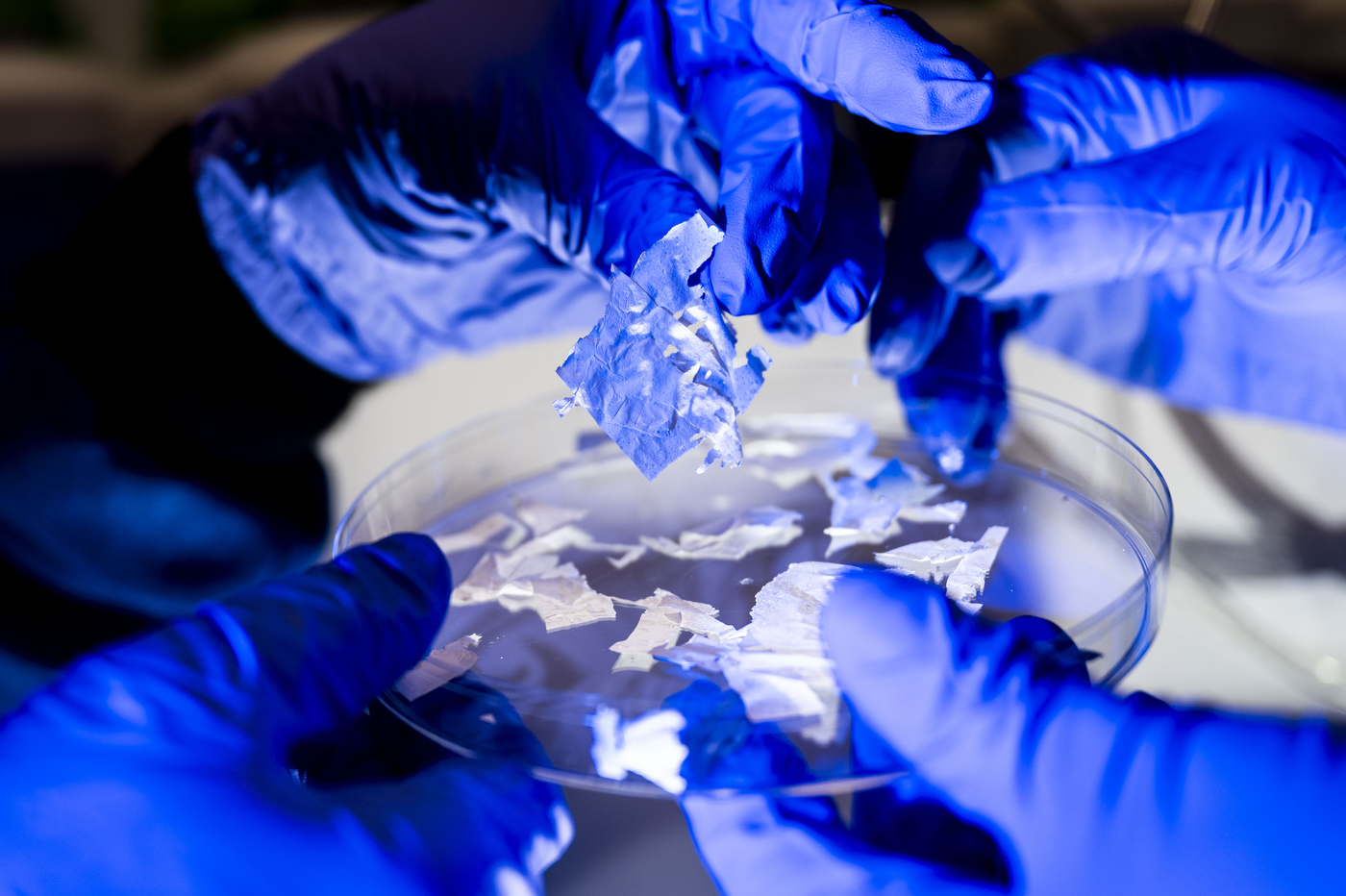

Northeastern University researchers have discovered that materials used in the development of transient electronics — devices designed to biodegrade at the end of their life — can break down into microplastics, casting doubt on the true dissolvability of these devices over time.

One particular polymer material, PEDOT:PSS, which is popularly used in medical applications, has been found to persist for more than eight years and its degradation could lead to the formation of microplastic fragments, according to Ravinder Dahiya, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Northeastern University and one of the lead authors of the research.

Dahiya, who was recently awarded the Celebrating Editorial Impact Award by Springer Nature for his work on flexible electronics, has a keen interest in understanding how electrical systems can be prevented from turning into eventual e-waste.

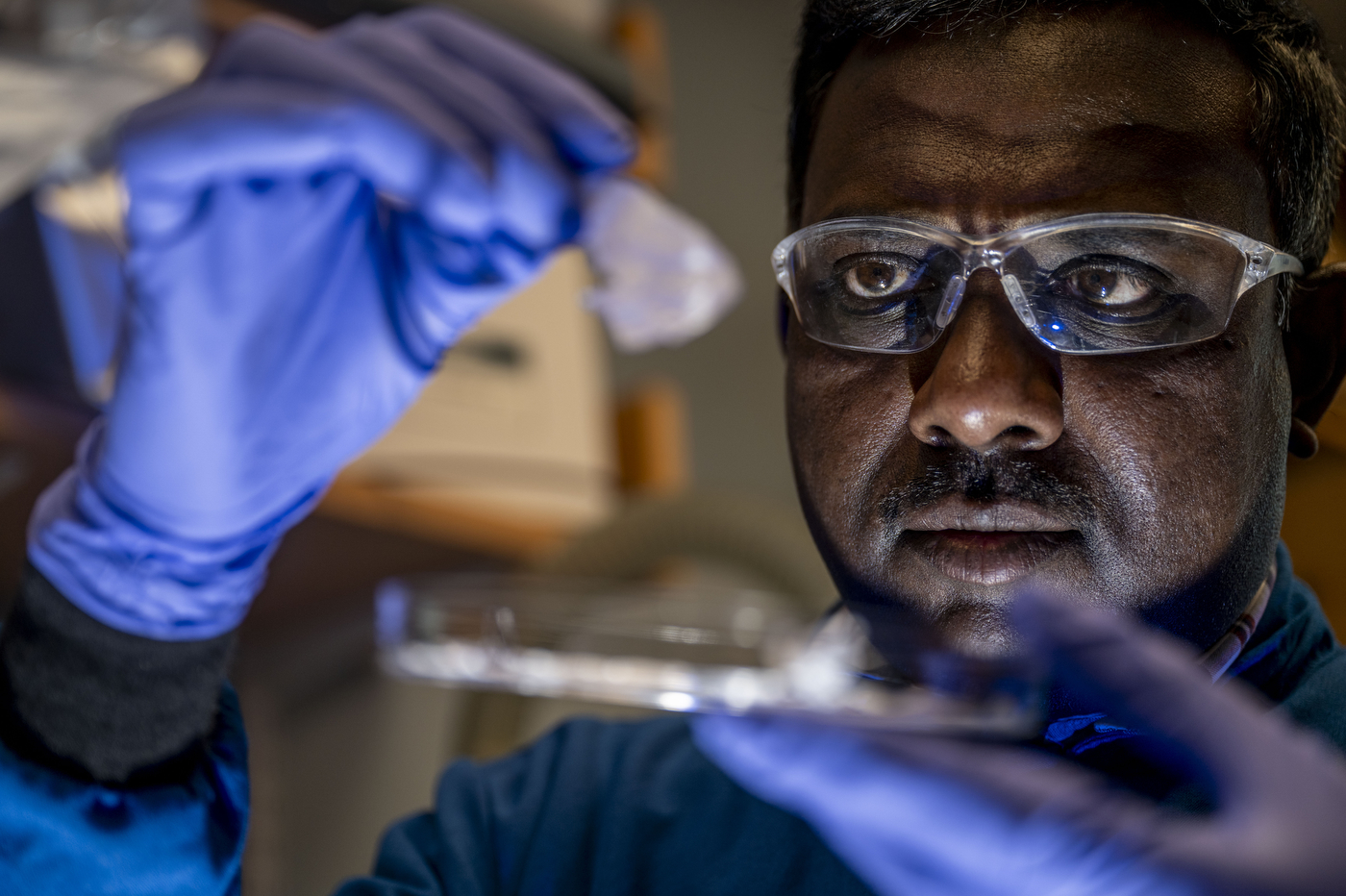

In the research, which was published this year, Dahiya and Sofia Sandhu, a former post doctoral researcher in his lab, investigated the biodegradability of two transient electronic devices — a partly degradable pressure sensor and a fully degradable photo detector.

In their observations, they highlighted the importance of proper material selection in the development of these technologies. Whereas polymer materials such as cellulose and silk fibroin have high rates of degradation and release byproducts that are not harmful to the environment, others can be quite dangerous, such as the previously mentioned PEDOT:PSS.

“You have to look at these materials carefully,” Dahiya said. “Normally at the end of their life, electronics are dumped into the soil. When you put an electronic board in soil, we need to understand if the electronic board, during the degradation process, is enriching the soil or if the soil is unaffected. In some cases, degradation might damage the soil permanently, and that is a big environmental and health issue.”

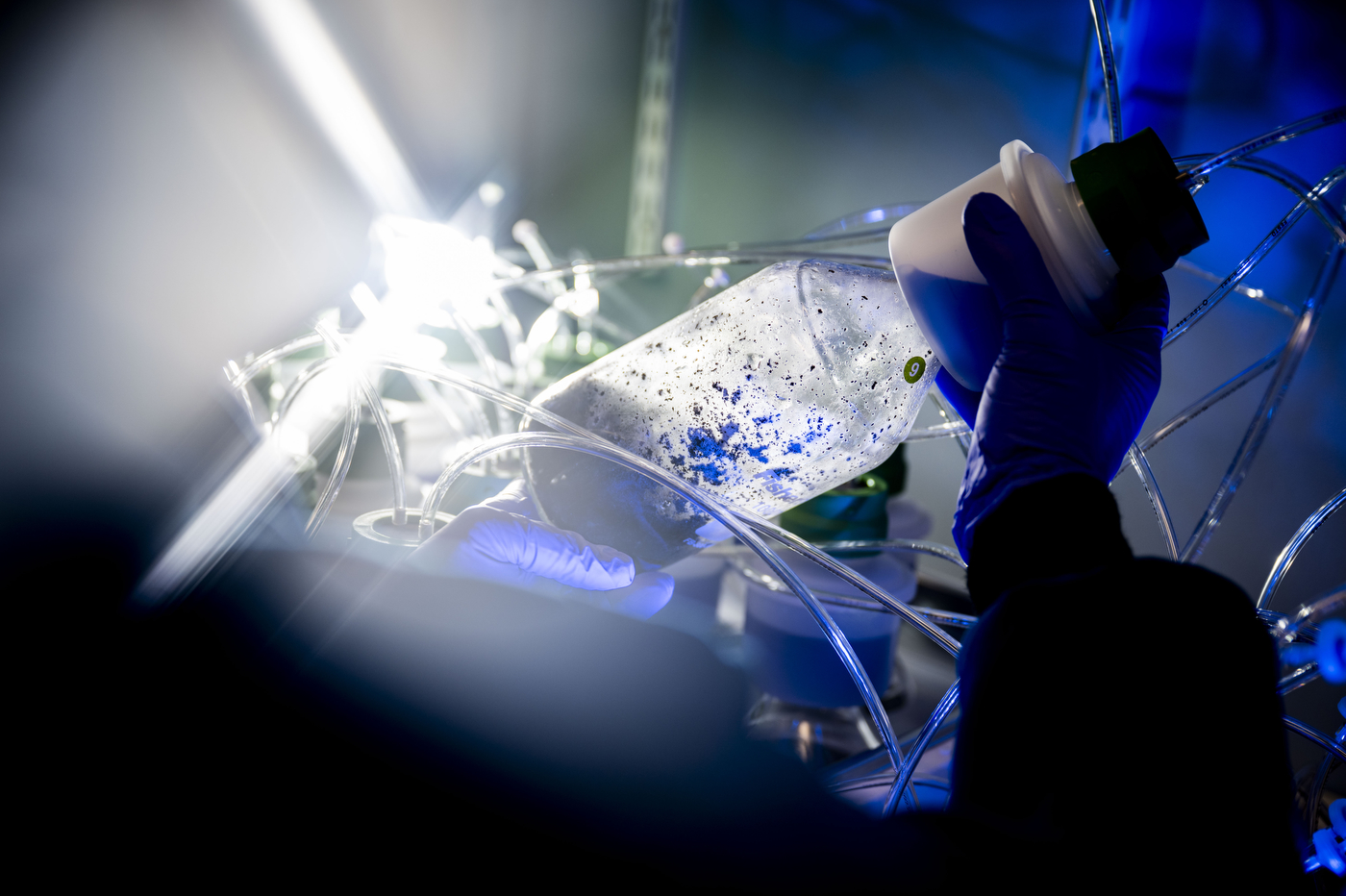

Monika Swami, a doctoral student in Dahiya’s lab, is leading research on a new degradational study to better understand how polymers and polymer-based devices degrade in soil and their byproducts. For this study, she is focusing on their production of carbon dioxide, which helps determine the rate of degradation.

“Currently, we are running a six-month degradation [test], and we are checking how long it takes to degrade fully and to understand the maximum amount of CO2 that is generated out of these organic compounds,” she said.

Transient electronics have gained popularity over the past decade, particularly in the development of medical devices like edible electronics and dissolvable stitches, Dahiya explained, and interest is growing.

The global biodegradable electronics polymers market size was estimated at $126.47 million in 2024 and is projected to reach $246 million by 2033, according to the market research firm Grand View Research.

In addition to examining the types of materials that make up transient electronics, another important environmental factor that Dahiya is investigating is the manufacturing processes behind them.

Globally, electronics manufacturing is extremely resource-intensive and largely linear — make, use and dispose, which is not environmentally friendly, Dahiya explains.

For example, one silicon wafer, a component used to make computer chips, can require as much as 6,000 liters of water mixed with an assortment of harmful chemicals to be fabricated, he said.

“There are millions of wafers processed every day,” Dahiya said. “You are consuming so much water, and because of the chemical mix, it becomes wastewater.”

There is already a global water scarcity problem, with 40 percent of current semiconductor manufacturing facilities located in watersheds expected to face “severe water stress risks” by 2030, according to The World Economic Forum. So, manufacturers should be thinking about using less water, not more, he explained.

A better way for electronics to be manufactured is through a circular system, Daihya explained, where discarded materials can be repurposed for fabrication and many electronic systems are biodegradable and naturally enrich soil or dissolve into water.

“Our long-term goal is to replace all these materials with eco-friendly machines, and eventually develop electronics that don’t require electronic waste handling [at all],” he said.