Your body is full of medicine — these researchers have finally discovered a way to synthesize it

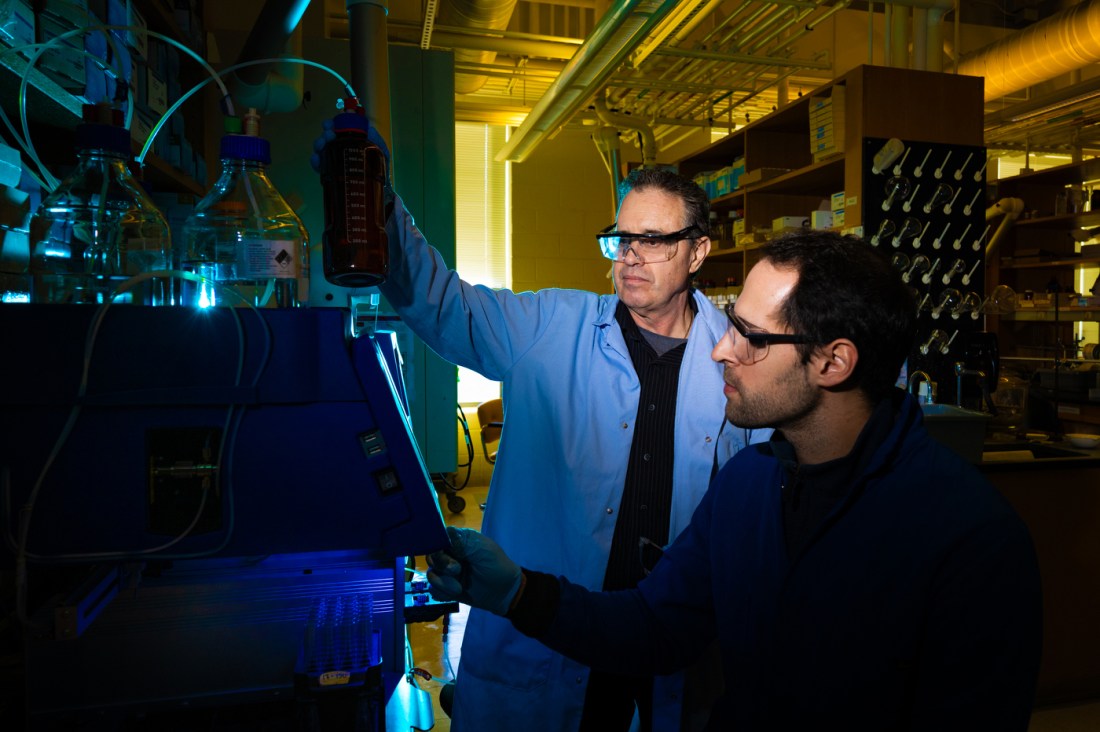

Northeastern’s Center for Drug Discovery has discovered a way to synthesize cannabinoids endogenous to the human body, which have wide application to drug discovery and creation.

Northeastern University researchers have made a breakthrough drug discovery, developing the first synthetic endogenous cannabinoid compound, with repercussions for new therapeutics from pain and inflammation to cancer.

Spyros P. Nikas, an associate research professor in Northeastern’s Center for Drug Discovery, says that the discovery hinges on the distinction between two different kinds of cannabinoid chemicals, endogenous and exogenous.

Exogenous cannabinoids are those produced outside the human body, like THC or CBD, both derived from the cannabis plant and present in marijuana.

Our own bodies, however, are also producing cannabinoids all the time. Called endogenous cannabinoids — or just “endocannabinoids” — these chemicals “modulate a wide range of physiological and pathophysiological responses,” Nikas says, processes that include mood, inflammation and even neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Cannabinoids — not just cannabis

Endocannabinoids don’t have the same structure as the plant-derived cannabinoids, “but they do exactly the same job,” says Alexandros Makriyannis, the George D. Behrakis chair of the department of chemistry and chemical biology.

The cannabinoid system within the human body — “combining endocannabinoids, receptors and enzymes” — Nikas says, “exists everywhere with high abundance in the central nervous system.”

Due to its prominence, Nikas calls it “a system that is responsible for the homeostasis of the human being.”

The receptors that bind with cannabinoids, called CB1 and CB2, are also found throughout the body, but “they have different distribution in different tissues and organs,” Nikas says.

Drugs that target the CB1 and CB2 receptors do exist already in medicine — for instance, to prevent vomiting in chemotherapy patients — but these are derived from the exogenous cannabinoids, and thus also exhibit the cannabis plant’s side effects, from hallucinations to dependence, Nikas says.

Drugs derived from endocannabinoids “are not expected to have these side effects,” Nikas says, as they are made inside our own, but the synthetic variety could still “have a wide range of therapeutic utility.”

If researchers can produce synthetic endocannabinoids, they should come with all the medical benefits of our own naturally created endocannabinoids without the attendant side effects of exogenous cannabinoids. The problem is how unstable these synthetics usually are.

Mirrored solutions

Editor’s Picks

Endocannabinoids break down quickly inside the body. Part of what’s revolutionary about these new synthetic endocannabinoids is that they are more potent and stable than any previously discovered, according to Nikas.

He says that they solved the problem through something called “chirality.”

Derived from the Greek word for “hand,” chirality refers to a mirrored property, where the reflection doesn’t perfectly match the original — like our hands, which don’t perfectly mirror one another.

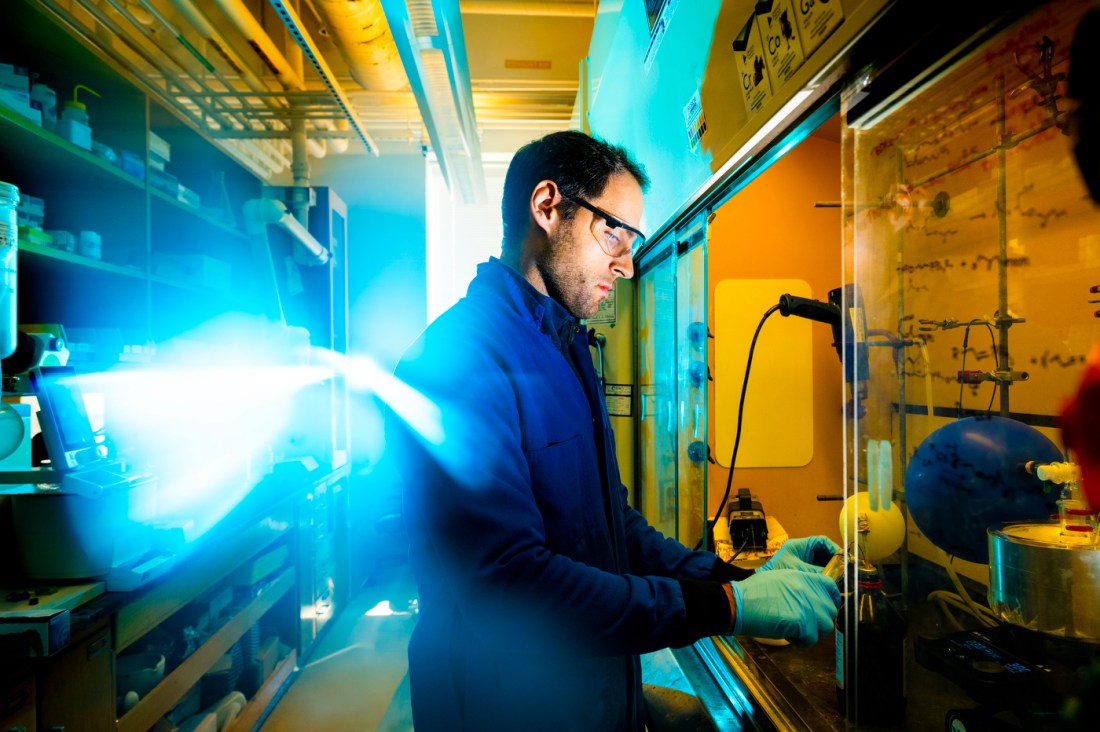

The Center for Drug Discovery used a “nature-related chiral approach in order to make these compounds much more potent and metabolically resistant,” Nikas says. “In nature everything is inherently chiral, this includes all proteins, receptors and enzymes.”

To make their synthetic endocannabinoid molecule chiral, Makriyannis says they used a “simple but ingenious approach”: They attached one methyl group — a simple hydrocarbon — to the endocannabinoid’s structure.

“It’s a question of fit,” Makriyannis continues. By leveraging chirality, the synthetic endocannabinoid now “fits” into the CB1 and CB2 receptors.

That methyl group also greatly increased the endocannabinoid’s stability and selectivity. “The more selective the better,” Makriyannis continues, as this will prevent the synthetic endocannabinoid from binding to receptors it doesn’t have any business binding to.

The CB1 and CB2 receptors can now “recognize our compound while simultaneously blocking enzymes from accessing critical ‘soft spots.’ As a result, the novel chiral endocannabinoids exhibit exceptional biological potency and robust metabolic stability,” Nikas says.

Next comes application

They have already shown the endocannabinoid’s effectiveness as an analgesic in mice, but Nikas notes that cannabinoids have applications far beyond mood (as in recreational cannabis use) or pain alleviation. Use cases include protecting from strokes and neurodegenerative disorders, including dementia, and even obesity. “All the energy balance in the organism,” he says.

“Next to morphine, cannabis is the next best way to reduce pain,” Makriyannis previously told Northeastern Global News.

“It’s not only mood. Mood is little,” Nikas says.

Nikas says that they have started testing applications for their new molecule, specifically in protecting against strokes and even “reversal of the stroke’s effects after it happens.” They will also test it against other pain relief options for inflammation, cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.

In describing just how far ahead the Center for Drug Discovery is on this important breakthrough, Nikas says, “We are without any competitor now, because we are very far — at the very top — on this endocannabinoid chemistry.”