The new multi-purpose athletics and recreation complex will be fossil-fuel-free and use rainwater for the ice rink

The complex replacing the Matthews. Arena is being built to meet ‘aggressive’ standards for sustainability and energy efficiency.

The new multi-purpose athletics and recreation complex replacing Matthews Arena will harness the power of nature available onsite to meet the building’s demands for water, heat and electricity.

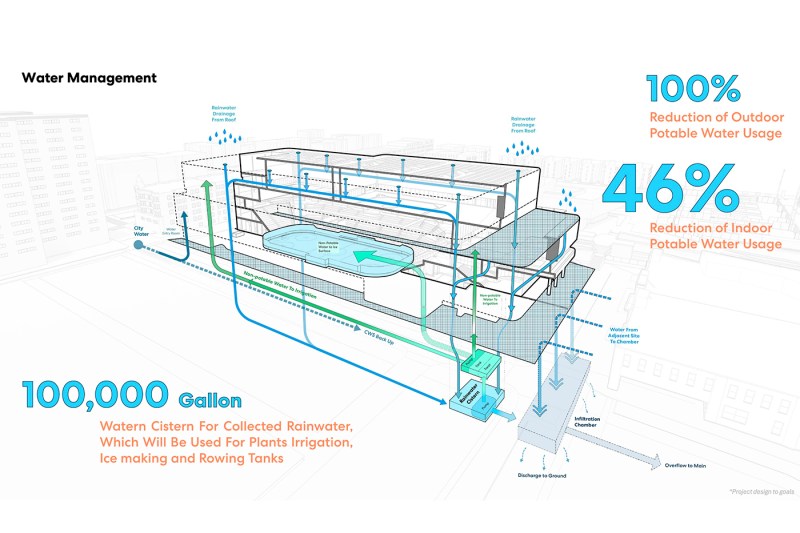

Rainfall collected from the roof will be used for the ice hockey rink and rowing tanks, and to water native plants in a rooftop terrace garden.

A grid of geothermal wells under the 310,00-square-foot building will meet most of the complex’s cooling and heating needs, while solar panels on the roof will use the sun’s energy to offset part of the demand for electricity.

Even before construction has started, the complex is making history as a model of sustainability and heat recovery, says Jacob Glickel, Northeastern University’s director of sustainability operations.

The innovative technologies being employed are “leaps and bounds” over what was possible even a couple of years ago, he says. “It really shows where we’re headed” with campus sustainability.

Tyler Hinckley, team leader of the project for the architectural design firm Perkins&Will, said the new complex will include an all-electric system, down to electric induction cooking equipment for the concessions.

“There are no fossil fuels on the site except for a backup generator,” he said.

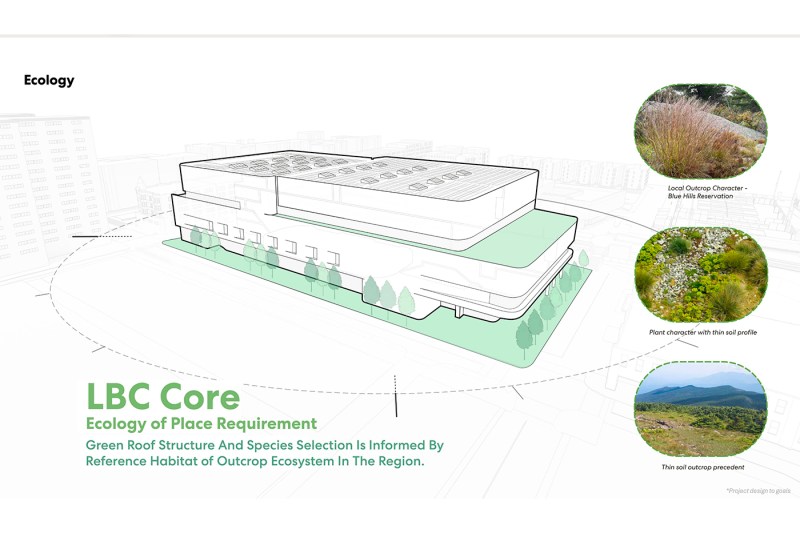

In constructing the new complex, Northeastern is seeking to attain Living Building Challenge (LBC) Core certification, one of the most advanced sustainable building standards in the country, Hinckley said.

Unlike LEED certification, which gives points for reduced negative impact, LBC Core projects have to meet verified standards in 10 areas, including responsible water use, energy, materials, ecology and even beauty, in order to be considered “regenerative.”

“It’s a very aggressive standard,” Hinckley said.

Geothermal energy

A major feature of the new complex is a geothermal exchange system that relies on relatively constant temperatures beneath the Earth’s surface to provide 80% of the new building’s requirements for heat and cooling, Hinckley said.

The system uses a geothermal loop, or network of underground pipes, filled with fluid to exchange heat with the Earth.

The network creates a source of heat in the winter and a sink for heat pulled out of the building in the summer using electric pumps, said Matthew Eckelman, a Northeastern professor of civil and environmental engineering.

“What’s different about a heat pump is that it’s not converting energy from electricity to heat,” said Eckelman, who visited the site with undergraduate and graduate students to see bore holes being drilled for the pipes.

“It’s just moving heat,” he said.

Typically, the geothermal grid is located in open areas, but this one will be located under the complex.

Thirty-five out of a total of 46 geothermal bore holes, 800 to 850 feet deep, have already been drilled and capped, Hinckley said. The rest will be installed during the construction of foundation supports for the new building.

In addition, the system will use waste heat from ice making for the hockey rink and adding it to the building’s energy loop, he said. “That’s capturing waste heat that would otherwise have been exhausted” into the atmosphere.

A 100,000-gallon cistern

Editor’s Picks

In what can only be described as a gigantic water-saving move, rainwater from the roof will be stored in a 100,000-gallon cistern under the building’s lobby.

“We’re taking all of the rainwater that falls on this building and reusing it on site for most of the things that don’t require potable water,” Hinckley said.

“The hockey players will be skating on ice made from water that fell on the roof of this building.”

Outside the building, underground infiltration pits will help absorb stormwater and prevent flooding.

Windows and walls: Energy savings and lots of light

Triple-glazed high-efficiency windows will drive down the new building’s energy load, as will “super-insulated” walls and roof, Hinckley said.

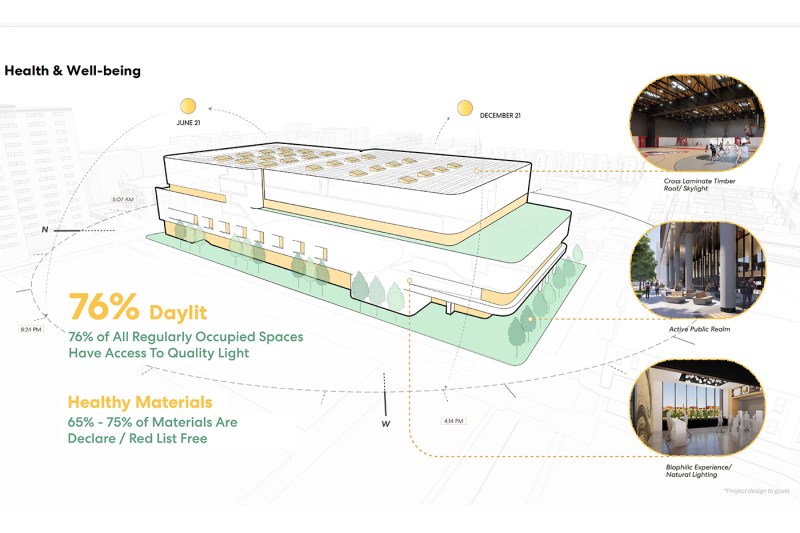

Part of the LBC Core challenge is connecting buildings to nature, which the new athletics and recreation complex will encourage through the use of light and windows, he said.

Hinckley said 75% of regularly occupied space will be functionally daylit. Even the basketball practice area will have the benefit of sunlight from skylights thanks to a glazing technique that cuts down on glare.

A roof that generates energy and wellness

Solar panels on the roof will generate approximately 590,650 kWH of electricity annually, offsetting up to 10% of the building’s energy usage, Hinckley said.

He said designs for the lower roof setback edging Gainsborough Street feature a “living roof” with native plantings and shrubs similar to those in Middlesex Fells, a state park just north of Boston.

Eco-friendly materials

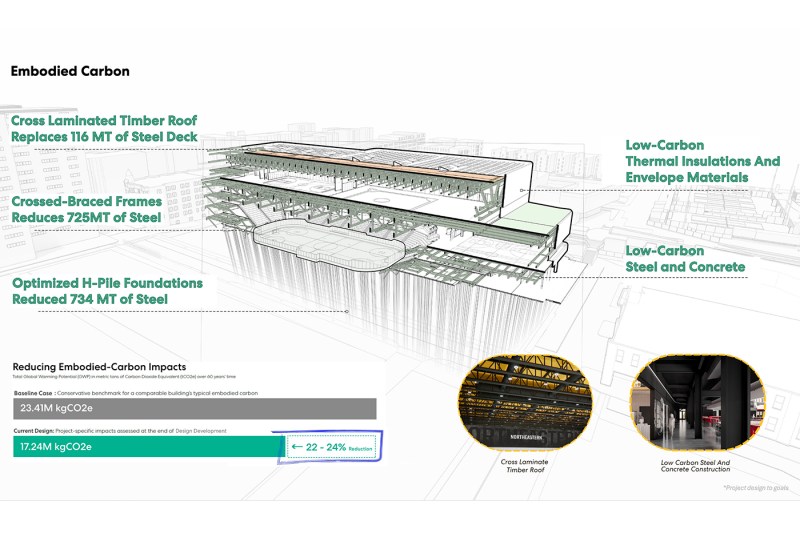

The structural deck on top of the building is being made of cross-laminated timber to reduce the amount of carbon that goes into construction, Hinckley said.

He said the building is being thoughtfully designed to reduce “embodied” carbon in materials by using, for instance, steel from plants that use electric arc furnaces instead of coal.

The new complex will be the first multi-use athletic and community recreation facility in a dense urban setting to achieve LBC Core certification, which speaks to the boundaries the project is pushing, Hinckley said.

“We’re doing something very new,” Glickel said. “We’re setting a new standard for sustainability that will influence how we design and build across all our campuses.”

Northeastern will “surgically” deconstruct Matthews Arena before building the new multi-purpose athletics and recreation complex, which is scheduled to be finished in the fall of 2028.

The complex will span the entire two-acre footprint of the old arena and will house 4,050 fans for hockey and 5,300 for basketball. It will include an additional 54,000 square feet for recreational use, including for ceremonies, concerts and other events. The venue will simultaneously accommodate an array of activities.