Scientific discovery was slower when women were ignored, research shows

The cross-campus Northeastern project found that scientific truths would have been uncovered faster if female research had been considered.

LONDON — As far as nicknames go, the moniker “Mad Madge” would not suggest that Margaret Cavendish enjoyed the full respect of her peers.

A poet, philosopher, scientist, playwright and fiction writer, the 17th-century duchess had a multitude of disciplines and was published under her own name in a period when women writers were either anonymous or ignored.

But Cavendish’s work at the time, while widely discussed, was often dismissed, particularly by fellow scientists, explained Sarah Connell, associate director of the NULab for Digital Humanities and Computational Social Science.

“She was certainly visible in a way that a lot of her contemporaries were not,” said Connell, “but it was often with this sort of disparagement, this sense that she was not worth taking seriously.”

A reappraisal has long since been underway of Cavendish’s achievements, and a project by Northeastern University has looked to take that further by analyzing her impact on the scientific community of her day.

That project, “New digital methods for understanding the impacts of early women writers on the development of science and philosophy,” has brought together researchers — philosophers Peter West and Brian Ball, along with English academics Connell and Julia Flanders — working on the university’s London and Boston campuses. They used Cavendish as a case study for understanding the impact of arguments advanced by marginalized female minds.

In 1667, Cavendish was the first woman invited to a meeting of the Royal Society in England, the oldest continuously existing scientific academy in the world. Early male fellows included architect Christopher Wren and physicist Isaac Newton, but it would take until 1945 for women to be accepted into the academy, and the organization has never been led by a woman.

Ball applied his previous research, involving networking how social media misinformation spreads, to create simulations that established the connections that Cavendish had with fellows at the Royal Society.

The simulation created a timeline of how and when society fellows changed their opinions and compared it to when Cavendish produced statements or published works. The team also produced a type of historical counterfactual, examining “what if” Cavendish had been better connected and her findings more widely accepted during her lifetime.

“One of the things that came out of the simulation,” said Ball, “was that when she’s better connected to those characters, actually, it is not just Cavendish who does better in approaching the truth more quickly. … We found that the Royal Society as a community gets to the truth faster — in fact, significantly faster.”

Connell said the joint research was driven by a desire to give Cavendish her proper due, rather than see her — as she has traditionally been — as an “outlier,” a rare leading female scientific figure of her age.

“What we’re trying to say is — let’s not treat her as a curiosity,” added Connell.

Editor’s Picks

The Boston-based researcher is also associate director of Northeastern’s Women Writers Project, which has made 475 historic texts available online since 1988.

The digital library involves painstakingly digitally transcribing books and manuscripts dating between 1526 and 1850. They are then hand-encoded by students to apply a textual model that gives added details to a reader, ranging from highlighting quotations to describing the physical condition of the source material. Connell described the work as a “labor of love and care.”

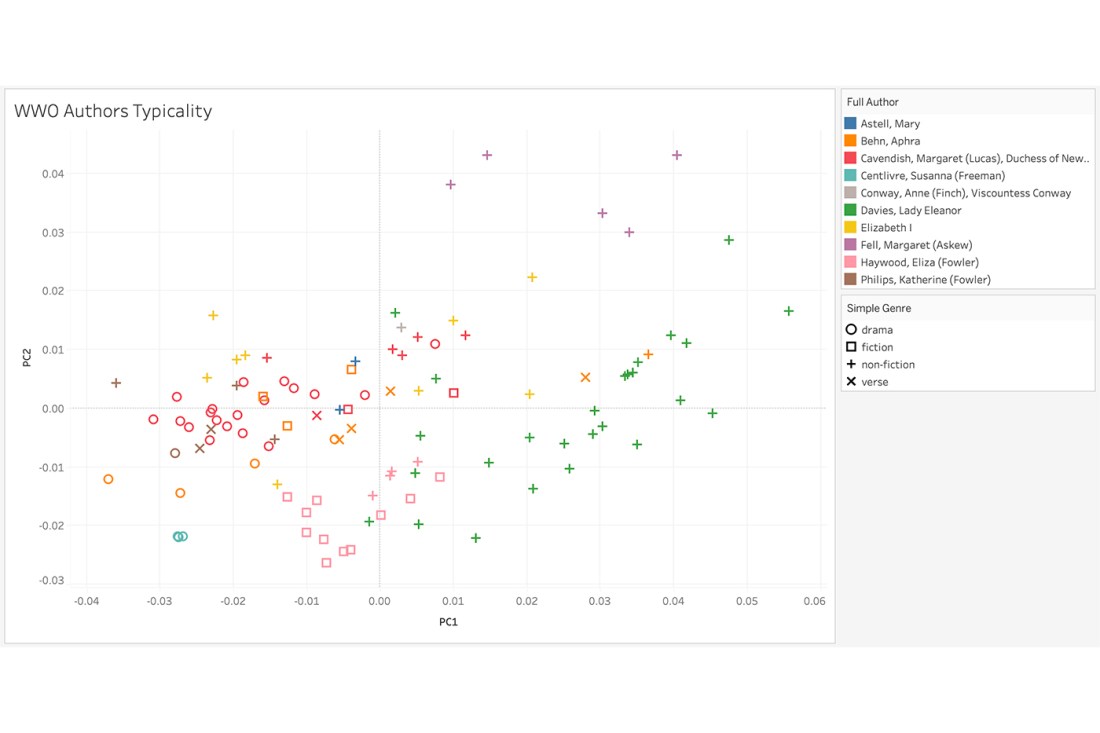

Cavendish proved an easy pick for the joint study as her works are “extraordinarily well represented” in the Women Writers Project’s online collection, said Connell. The array of texts available allowed her to prove just how stand-out Margaret Cavendish was as a thinker, finding that she was “truly distinctive” among the archive’s authors. With her wide range of writing, Cavendish was in a field of her own, according to the researchers’ modelling.

West, who studies marginalized figures in philosophy and edits a journal dedicated to Cavendish’s writings, said working with what Connell calls “digital humanities” methods has allowed him to counter entrenched narratives about who the most influential people have been during the history of philosophy.

The assistant professor described having Connell’s versions of Cavendish’s texts as akin to the difference between a printed topographic map and an interactive online service such as Google Maps, creating a “much richer version of a text” and making them more easily accessible for researchers.

One of the expected outcomes of the collaboration, which was funded by a Northeastern University Tier 1 mentored grant, is an online exhibition and an academic paper.

It also saw West, in collaboration with The Philosopher journal, host a symposium on Oct. 27 involving experts in the fields of women in science, philosophy and literature.

Among them was Dame Athene Donald, a British physicist and Royal Society fellow. Donald told the audience that women working in science continue to be sidelined, arguing that senior male managers have been known to take the credit for the work of junior-ranking female colleagues and that women can “feel excluded” in a male-dominated sector.

“It is very easy for people to believe there are no more problems, and that just isn’t the case,” said Donald. “There is a lot of subtle bias, right from birth.”