How one high schooler’s ambition led to an AI tool to restore ancient art

Working in Zheng Zheng’s Data Science and Artificial Intelligence lab at Northeastern, 11th grader Qianhao Han proposed an AI tool to help restore ancient art.

Zheng Zheng started painting when he was 6 years old. Now, as an assistant teaching professor in Northeastern University’s College of Engineering, he wants to use artificial intelligence to restore historic murals.

The inspiration came from a teenager. Qianhao Han was in the 10th grade when she emailed Zheng out of the blue, inquiring how she could get involved in research. The Toronto high school student said she had reached out to several professors, to no avail. But Zheng, whose laboratory is located at Northeastern’s Toronto campus, saw potential in the ambitious young person and replied.

It turned out that Han had a passion for both art and science and had earlier participated in robotics competitions and taught herself the basics of AI. But she craved “more professional guidance,” she said.

Zheng invited her to give a presentation on one of her projects that uses AI to detect pedestrians and signal to cars when they’re crossing the street.

Soon, Han was working in the lab, shoulder-to-shoulder with Zheng’s graduate students — like Jincheng Jiang, a master’s student also working on the mural restoration project.

Using AI to build a tool for art restorers is actually “something that I proposed,” Han says.

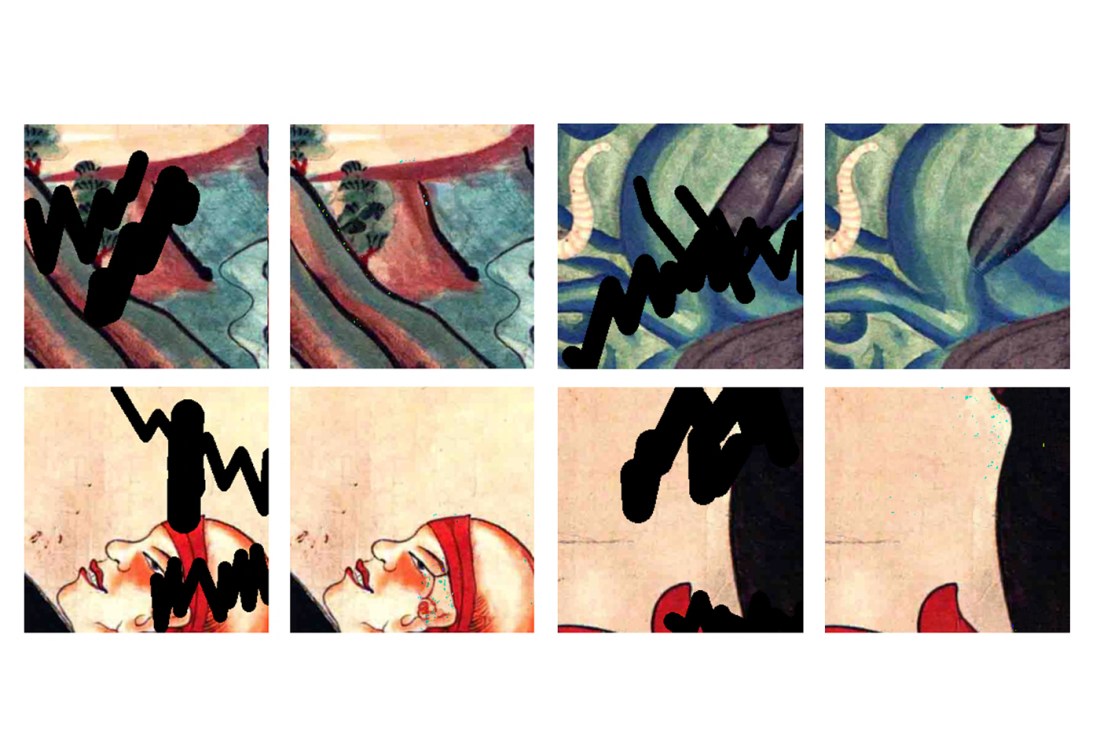

The program, which they call MurFact AI, or just MurFact, concludes a mural’s material that might be either missing or distorted and then generates its interpretation of the image.

Advanced technology alongside ancient murals

While the technique applies to many kinds of murals, both Han and Zheng were inspired by those of ancient China. “We love history,” Zheng said, smiling.

Zheng explained that restoring murals is far trickier than restoring other art, like a photograph. This is partly due to the sheer scale of some murals, which can stretch over 10 meters, but also because some murals are displayed outside and exposed to damage from humidity, sunlight or human factors, Zheng said.

In addition, murals are three dimensional, unlike the flat image of a photograph, and Zheng’s AI would need to take into consideration brush strokes and texture.

The program has to be able to understand the different kinds of damage it confronts, whether it’s a hole with a ragged edge or a portion of the mural that’s been bleached white by the sun.

Cultural context also matters, Zheng said. He cited the example of a damaged image of a Buddha.

“Maybe the hand, for example, is missing. Then we need to know some of the history about this Buddha, and then to infer what kind of gesture that Buddha may have,” he said.

The program thus must make inferences not only about the image it sees, but about the cultural contexts that produced that image — even for a mural that might be 1,000 years old.

Han noted that the murals’ histories are not just art. “They also represent a lot of the social, religious and philosophical ideas of ancient cultures,” she said.

Editor’s Picks

Training the program to get to this level of cultural fluency involves human expertise, someone who will go through thousands of images of murals and categorize them by any number of metrics.

“For example, if we want to distinguish whether a picture is a cat or dog, you need to have a lot of data to say, ‘Okay, this picture is a dog, this picture is a cat,’” Zheng said.

All these labels are supplied “by humans, by experts,” he added.

Zheng says that their program is built on the same architecture as modern large language models like ChatGPT. Once MurFact has a database of coherent labels, it can make semantic determinations based on what it sees. It “learns” the mural in a grammatical way the same way ChatGPT “learns” a language.

Tools, not replacements

Zheng hopes that MurFact can eventually become an app that helps restorationists make their decisions — not replace them.

Traditional restoration efforts can take years, Zheng says, as the restorationist makes thousands of small — and big — decisions in their work. He sees a world where MurFact can “help somehow speed up or enhance or preserve all these invaluable artifacts more efficiently.”

That this project came from someone outside the university, and a high schooler no less, “reflects our Northeastern spirit, giving back to our community and offering opportunities” back to locals, Zheng said.

Han agreed.

“It was a really good way for me to see, ‘Oh, I really enjoy this, and I want to pursue this in the future,’” she said.