This double Husky created her own co-op working on life-changing cancer therapies

CAR T-cell therapy can serve as a life saving treatment for blood cancers, but comes with complications. This master’s degree student’s research may help change that.

CAR T-cell therapy can be a useful tool for treating cancer. But it has limitations so far as the serious side effects it can cause. If scientists can figure out a solution, then it can pave the way for better treatment for patients with blood cancers.

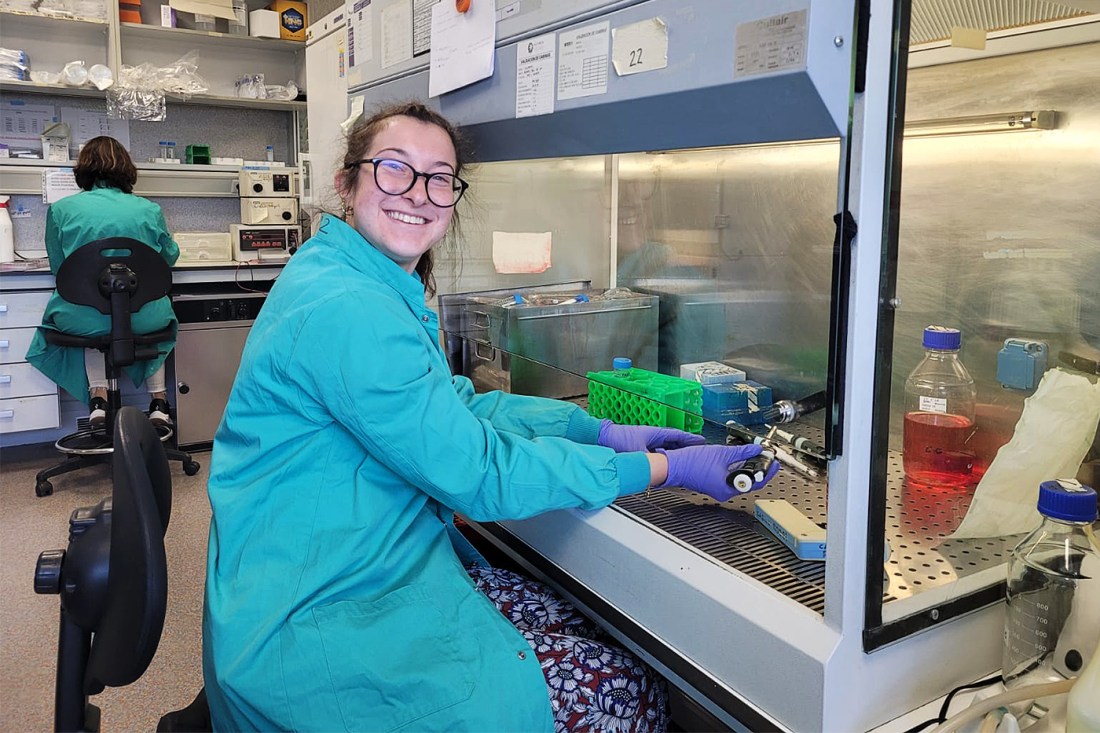

Federica Ciummo, a Northeastern student pursuing her master’s degree in cell and gene therapies, worked on this over the summer. Her co-op at Severo Ochoa Molecular Biology Center in Madrid gave her hands-on experience working on improvements for CAR T-cell therapy.

“It was so great,” she said. “I enjoyed it a lot more than I thought I would. I had a lot of autonomy and more understanding of exactly the things I was doing (than in previous research settings).”

And the co-op was of her own creation.

Ciummo, who got her bachelors from Northeastern in behavioral neuroscience, is originally from Milan, Italy, and knew she wanted to try working closer to home when doing a co-op for her master’s degree.

“When I was in undergrad, I didn’t feel the need to go abroad, because for me, being here was my abroad experience,” she said. “But then while in my master’s, I realized maybe I want to explore somewhere else. I started looking around Europe because eventually, I do plan to move home, so I figured it’s a good way to test whether the working experience back home is feasible.”

When Ciummo began looking for co-ops, she found there were a lot of biotech companies in Basel, Switzerland, but they didn’t offer the kind of research she wanted to focus on as someone studying cell and gene therapy.

Luckily, Ciummo had a connection at the Severo Ochoa Molecular Biology Center who was interested in taking her on as a co-op. With 90 labs, the center had a variety of studies going on which allowed Ciummo to join in research relevant to her master’s.

Ciummo’s main interest is in genetics. In the first year of her master’s degree program, she took a course in immunology and fell in love, especially as she realized how tied it is to cell and gene therapy. A lot of current research projects are tied to immune-based cell and gene modulation, she added.

“I want to go to medical school, but I was always super interested in genetics and how that could be applied in the content of medicine and currently incurable, untreatable diseases and genuinely change the lives of many people,” she said.

Ciummo was particularly interested in learning more CAR T-cell therapy for T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (TALL) after attending a lecture about this at Northeastern. When she learned that was an area of research at the biology center, she jumped at the chance to join the team.

“When I was talking to the lab to see if they were a good fit, they were explaining the work they were doing (on this) and I was like ‘whoa,’” she said. “It was the kind of excitement you get when you’re a little kid. It’s just magical and I was really excited to start.”

The lab Ciummo worked at focused on the modulation of T-cells to combat TALL, testing CAR T constructs which are a common therapy for blood cancers. CAR T-cell therapy “absolutely revolutionized” the field of blood cancer treatments, Ciummo said, and is being used more in clinical trials. This type of therapy helps teach the body’s immune system how to recognize and fight cancer.

However, Ciummo explained that this type of therapy has two shortcomings. It can cause a really intense burst of toxic chemicals called cytokines that attack and kill cells. This is great for killing cancer, but the release can become so excessive that it causes something called cytokine release syndrome where the immune system overreacts and starts attacking healthy cells. This can be treated, but it poses serious risks.

These T-cells also have a short lifespan, which Ciummo said means that if the patient has a relapse, they have to get the therapy again.

Editor’s Picks

What Ciummo’s lab worked on this summer was a construct to fix these two issues specifically for patients with TALL, starting with developing a construct for the T-cells that was more similar to their natural constructs.

“We basically put a new receptor on the surface of a T-cell,” Ciummo explained. “And this receptor is able to recognize an epitope which is something that sits on top of a tumorous cell.”

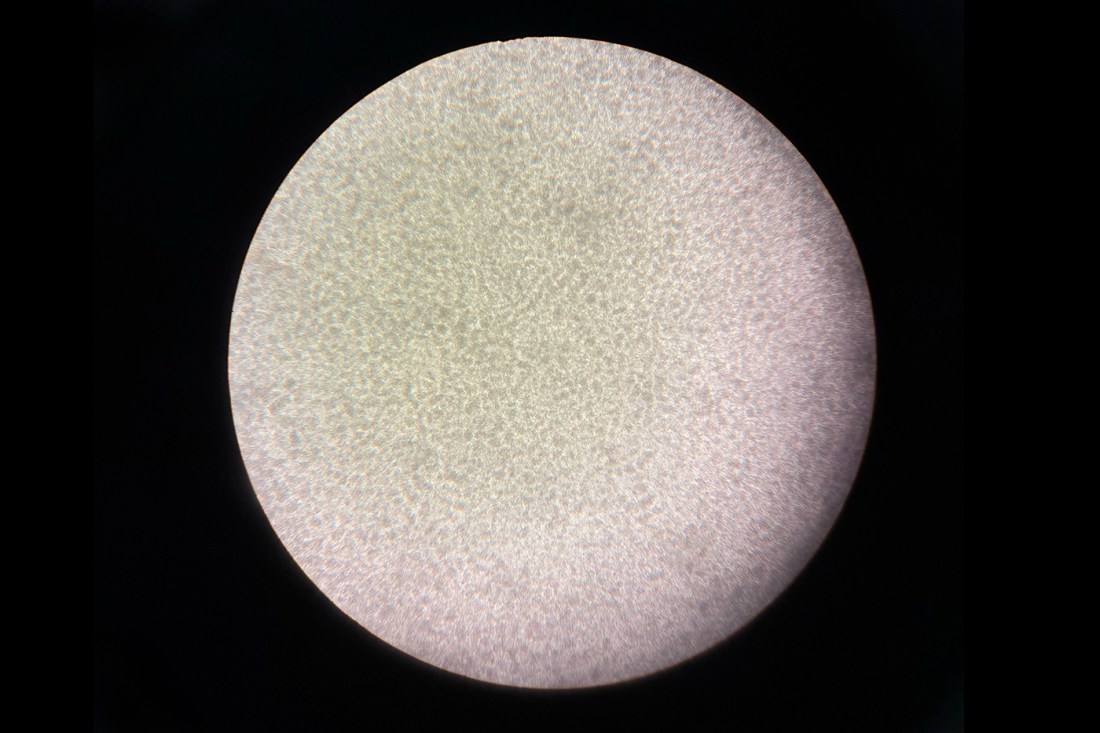

On many days, she’d get to the lab and go to the culture room to see if cells needed passaging — being moved so they had space to grow. The team would also run experiments with flow cytometry where they passed cultures through a machine to see the percentage of cells tagged with a certain marker. This indicated to them how much cytokine release there was happening as well as if cells were getting exhausted in dying.

They could also see where cells were in their cycle and different levels of effectiveness. They also did staining to see the markers.

In between, the team maintained camaraderie, often eating meals together.

“We would spend hours doing that,” Ciummo said. “The thing I liked the most was the group I was with felt like a little family. Everyone was running their own study, but yet everyone helped each other with their stuff all the time. It was super supportive environment.”

Ultimately, they found their experiments were successful.

“This reduces the rejection and increases the lifespan because it’s less odd to the cell,” Ciummo continued. “Anytime you modulate a cell with something that doesn’t naturally exist, there’s a tendency (for other cells) to kill it off. The construct we were developing was more natural. What we found was that it was able to continue being as effective the first time as the second time which is really, really beneficial in case of relapse so that patients don’t have to come in again and do another whole round of treatment.”

They also found this allowed a more specific release of the cytokines which reduced the odds of cytokine release syndrome.

The experience was helpful for Ciummo as she prepares for medical school.

“I’ve always worked in oncology and I’ve taken a pretty strong interest in how we can apply these therapies to treat cancer,” she said. “If I become a doctor, to not stay up to date on research is to be a bad doctor in that field. To have a background and to understand what’s being developed and how it’s being developed will definitely help me treat my own patients.”