From the ice caps to the moon: Northeastern professor charts military’s environmental adaptation

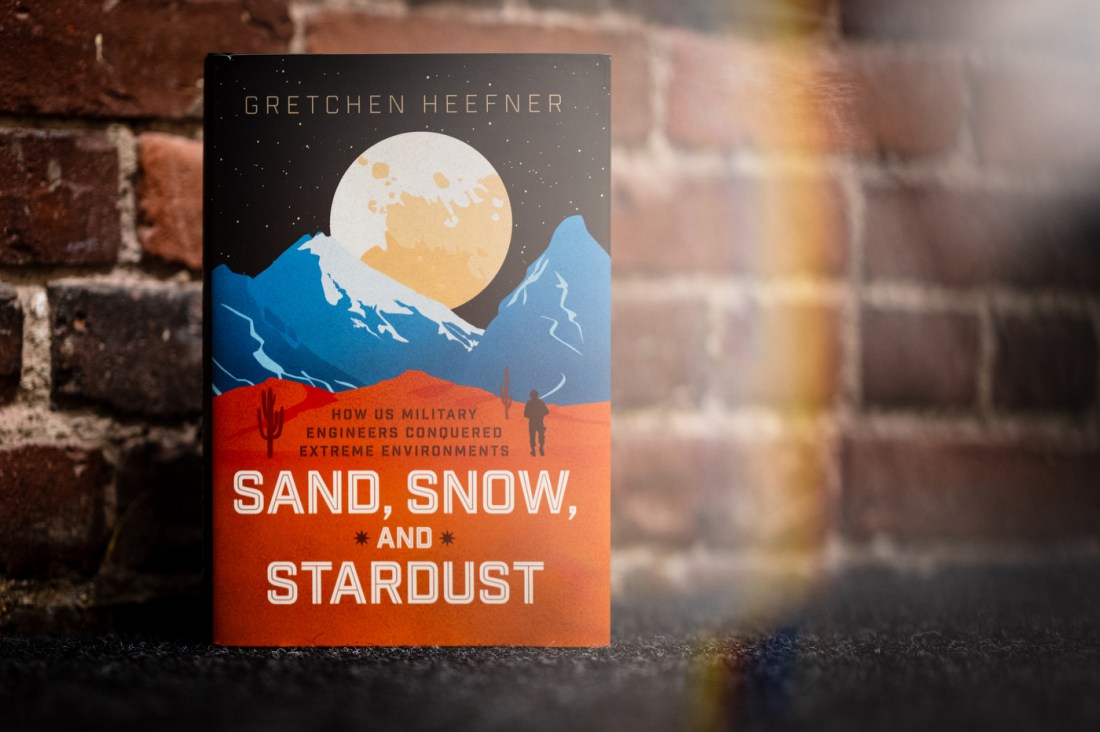

Gretchen Heefner’s second book, “Sand, Snow, and Stardust,” looks at the history of the U.S. military’s efforts to learn how to build bases in the most extreme places.

Did you know the U.S. Army once built a military base under ice caps in Greenland? Or made a model for a military base that would go on the moon?

In her latest book, “Sand, Snow, and Stardust: How the U.S. Military Conquered Extreme Environments,” Northeastern University history professor and department chair Gretchen Heefner looks into how the U.S. military learned to operate everywhere from the sand dunes of North Africa to the surface of the moon.

“The book is about the surprising, unexpected ways the U.S. Defense Department acquired expertise and information about extreme environments, places that were considered to be uninhabitable wastelands (like) the Arctic, the desert, and even outer space,” Heefner said. “(It looks at) how military engineers thought about building massive facilities in those kinds of places, places they had never been before and they had no experience in.”

Heefner’s latest book was inspired by her first, which examined how people in the Midwest responded to the deployment of missiles in their backyard during the Cold War.

As part of her research for her first book, she went to Virginia to study the archives of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the main construction agent for the American military both at home and abroad.

“It was a footnote to that book that drove me to the second project,” Heefner says. “I’ve been interested in the work they did. … (Army) engineers have to go and build everything. It’s so important, but something we don’t pay attention to. (When creating bases), they put the infrastructure in place, they put the roads down, the bridges, the communication lines, the runways for airplanes. That’s a key thing.”

“As I was doing the initial research, I kept running across the work they were doing overseas in the 1950s and ’60s. I sort of put a pin in that to go back to it later. ‘Sand, Snow, and Stardust’ came out of noticing that they were working in environments that I had not expected them to be in,” Heefner says.

Heefner’s book begins in the 1940s with Operation Torch. The U.S. military went to Northern Africa with plans to fight the Germans in a dry desert climate. Instead, they found the land in Morocco and Algeria rainy, cold and muddy. They had to ask for rain gear to be sent to them.

“Nobody can kind of understand why they need that because they’re in North Africa, and it’s supposed to be a desert,” she says. “It was this really obvious disconnect between what they thought they were going to find and what they prepared for and what they found. That led me to the rest of the book.”

Heefner added that the U.S. military realized from this experience during World War II that they needed to create standards for construction in order to be able to easily mobilize bases around the world, down to the types of screws used. And these standards needed to work in extreme environments around the world to avoid a repeat of the unpreparedness troops faced in Northern Africa.

Editor’s Picks

The book follows the U.S. military’s subsequent mission, which continued through the 1960s, to obtain what Heefner describes as “environmental intelligence,” where they learned how to construct and maintain bases in places with extreme climates, focusing on spots with unfamiliar materials (like the titular sand, snow and stardust).

This exploration, Heefner adds, was key to the maintenance of America’s global power throughout the 20th century.

“We think of guns and bombs as what military power is,” Heefner says. “My argument is that environmental knowledge, the ability to get anywhere in the world and ultimately the solar system, is central to how Americans construct their view of how they control things. After the war … there is a dramatic shift in the way the U.S. government is thinking about its relationships with the rest of the world.”

The book focuses on a number of bases, including one built in Tripoli, Libya and northeastern Greenland, the latter of which was built under the ice. It was meant to serve as an anchor base for military weapons, but ultimately failed.

Heefner said her book is about more than just the military operations, but the places they went and people living there, including some who got displaced in the process.

“I didn’t want to write a book just about the military,” she says. “I wanted to actually write a book about these places. A fair amount of the book (is also) the stories of people who interacted with these bases. Nobody cared about it, but I try to bring in these stories of individuals who … actually tried to insert themselves into the process, usually unsuccessfully. It gives us just a different way of thinking about it.”