How telling personal stories of measles infections can increase vaccination rates

How telling personal stories of measles infections can increase vaccination rates

Northeastern University public health experts were relieved to see Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., an avowed vaccine skeptic, post on X that “the most effective way to prevent measles is the MMR vaccine.”

They say it sends a strong message in the midst of a measles outbreak that has sickened more than 600 people this year, hospitalized more than 50 and killed at least two people, including unvaccinated schoolchildren in Texas.

What would make the post even more effective is personal stories from the families who lost children to measles, or from individuals who survived hospitalization, says Elizabeth Glowacki, a Northeastern assistant teaching professor who focuses on health communication, message design, persuasion and mobile health.

“The new messaging from (Kennedy) will be helpful for encouraging people to perhaps reconsider vaccines if they are hesitant,” Glowacki says.

But more needs to be done to frame the message, she says.

“Another effective method potentially could be focusing on the stories of these individuals who are living it,” Glowacki says. “Featuring the stories of families who lost children can be particularly effective. Whenever something happens, if children are sadly affected by it, I think that captures the public’s attention.”

Neil Maniar, director of Northeastern’s master of public health program, says he is happy to see evidence-based public health information is once again being promoted to help address the measles crisis.

“I think we have a long way to go, though,” he says. “We need to provide information in a way that families and communities are able to use to make informed decisions about their health.”

The importance of stories

The science behind vaccine safety is solid, with several studies disproving a connection between vaccines and autism, Glowacki says.

“A lot of the anti-vax movement is driven by stories” due to the lack of data between vaccines and autism, she says.

“I think that’s why it’s helpful that the opposing side also has their stories ready to go in terms of counteracting if people aren’t motivated by data,” Glowacki says. “How else can we speak to them?”

The families of 8-year-old Daisy Hildebrand, who was buried April 8 with Kennedy in attendance, and of 6-year-old Kayley Fehr, who died in February, have not come out in support of MMR shots.

Fehr’s father told Atlantic Monthly that his 6-year-old’s death was “God’s will.” Hildebrand’s father said in an interview with the Guardian that he heard some vaccinated family members got the measles “way worse than some of my other kids. … The vaccine was not effective.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 97% of the more than 600 people who have contracted measles in the 2025 were totally unvaccinated against measles and had not received either one of the two shots recommended by health officials.

In addition to the unvaccinated girls who died, public health officials are investigating the cause of death of an unvaccinated New Mexico man who tested positive for measles following his demise.

There are other ways to get personal stories out, including accounts from people who were very ill or hospitalized with measles, Glowacki says.

Editor’s Picks

The tiny ticks that cause Lyme seem to have superpowers that make them hard to kill. But you can protect yourself by following these steps

Trialled on Tower Bridge and ready for toxic zones — Northeastern students show off their market-ready engineering products in London

Barbara Lee, Mills College graduate and longtime U.S. representative, elected mayor of Oakland

Living tissues may form like avalanches, Northeastern researchers say — a discovery that could aid new treatments

Northeastern announces speakers for 2025 global campus commencements, and college and school ceremonies

And measles “is not just an individual concern,” she says. “It’s so contagious. It’s important to consider how community spaces are affected,” including church groups and school groups.

Having a leader from a faith community or other institution central to the community speak out in favor of the vaccines could be a powerful tool to have people immunized against measles, Glowacki says.

“People always look to see what’s going on around them, what the normative behavior is,” she says.

“We need to find a really solid group of communicators, people who can deliver a message in ways that speak to the groups who are most vulnerable,” Glowacki says. “It’s a matter of identifying the channels that are being used by these groups.”

Both of the children who died are from a Mennonite community in Gaines County. Mennonites do not have a formal policy against vaccination, but the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy says the population of Gaines is “highly unvaccinated,” with more than 300 cases of measles this year.

Kennedy is now facing backlash from anti-vaxxers for his post on the MMR vaccine.

“It would be great if we had done this much, much earlier,” Maniar says. “But it’s not too late to stem the tide,” he says.

Glowacki says Kennedy’s visit to Gaines County is an example of message tailoring, saying it could be an effective example of starting small to “eventually broaden out the message a bit.”

“I commend him for at least changing course, which we don’t always see in a lot of public officials,” Glowacki says. “I think we’re used to seeing public officials double down.”

She says she thinks anti-vaxxers will start to take immunization more seriously when awareness of measles “becomes more prevalent. Again, I really think the importance of featuring stories and experiences shouldn’t be overlooked.”

Health

-

The tiny ticks that cause Lyme seem to have superpowers that make them hard to kill. But you can protect yourself by following these steps

The tiny ticks that cause Lyme seem to have superpowers that make them hard to kill. But you can protect yourself by following these steps -

Build muscle strength if you want to live longer and healthier, Northeastern experts say

Build muscle strength if you want to live longer and healthier, Northeastern experts say -

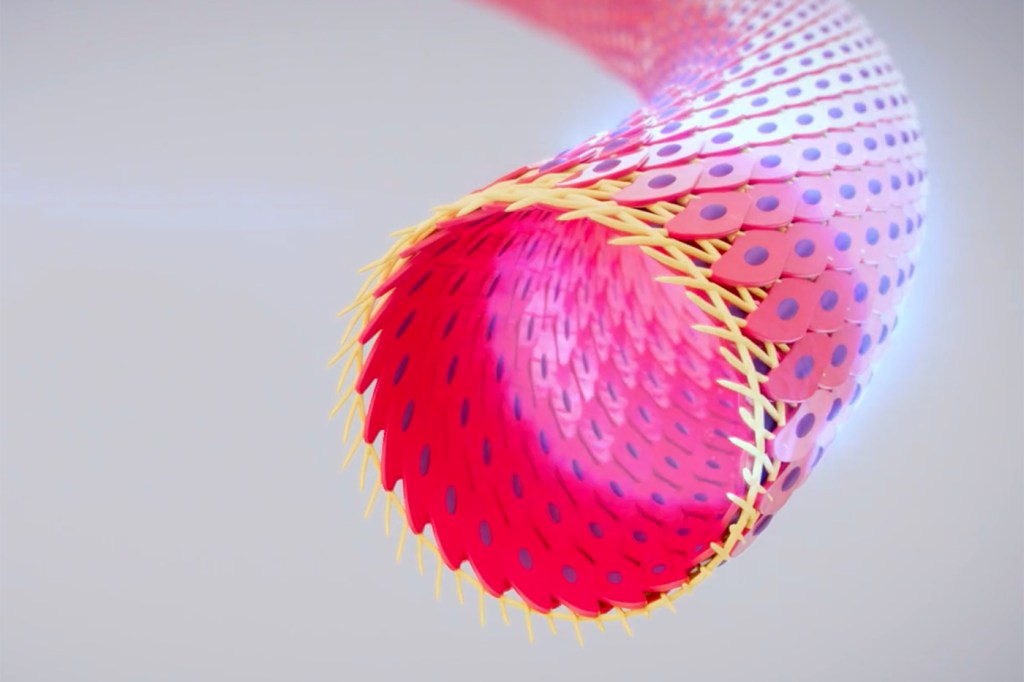

Northeastern researchers urge FDA to revoke approval of controversial artificial blood vessel

Northeastern researchers urge FDA to revoke approval of controversial artificial blood vessel