Can you survive eating the fruit of a ‘suicide’ tree, as in the HBO show ‘The White Lotus’?

How dangerous is the poison fruit from White Lotus? Jing-Ke Weng, Northeastern’s inaugural director of the Institute for Plant Human Interface, breaks it down.

The third season of “The White Lotus” wrapped Sunday night, capping off the popular HBO show’s most viewed season yet, which averaged about 15 million viewers per episode.

A major point of conversation online over the past few weeks has centered on the “suicide” tree featured in the show and the poisonous fruit it produces.

The suicide tree is very real and can be very dangerous, explains Jing-Ke Weng, a Northeastern professor of chemistry and chemical biology and the inaugural director of the Institute for Plant Human Interface, which studies the toxin made by the suicide tree plant and its relatives.

What is a suicide tree?

Otherwise known as a pong pong tree (or its scientific name, Cerbera odollam), the suicide tree is native to Southeast Asia. It gets its name from the poisonous seed kernels contained in the deadly fruit that grows from it.

Why is the fruit deadly to eat?

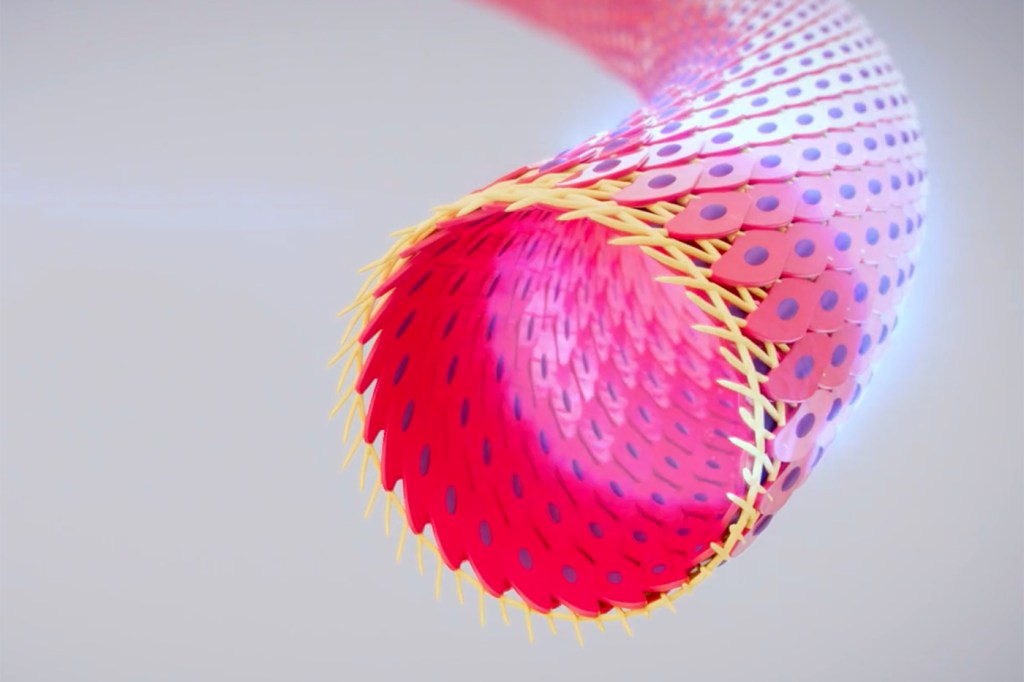

The kernels of fruit contain cerberin, which is a cardiac glycoside, a class of organic compound that attacks the heart and inhibits the production of sodium-potassium ATPase.

“These are membrane proteins localized on the membrane of many animal cells, including heart cells,” he says. “They help to maintain the potassium sodium balance outside and within the cell.”

While small doses of the seeds can be fatal, people can sometimes recover, Weng says.

Is the show scientifically accurate?

While he doesn’t watch “The White Lotus,” Weng says he appreciates the show spotlighting the pong pong tree.

“I’m glad to see they got the science right,” he says. “I think people just have a natural interest in toxic things. … People just like these stories. The fact that a popular show, which I do not watch, features scientifically legit toxic foods, is a really great way to trigger people’s natural interest in plants and plant chemistry.”

More in Arts & Entertainment

The ‘Minecraft’ movie is a box office smash. An expert explains why that’s good for gamers – and parents

Season 3 of ‘The White Lotus’ is again the talk of the town. What makes the show so popular?

Is your pet actually watching TV with you?

Why ‘The Great Gatsby’ still resonates a century after publication

What is the tree’s history?

It’s estimated that thousands of people have died from its effects over the years, and those deaths weren’t always the result of people inadvertently poisoning themselves.

In past centuries, people consumed the seed kernels as part of “trial by ordeals” similar to tasks like fetching stones out of boiling water or walking bare feet over coal to make up for their sins or prove their innocence, Weng says.

“This was one of the really ridiculous things people were forced to go through,” he says. “It usually kills people. Some people survived, not because they were innocent of [wrongdoing]. They were just a bit luckier, had a little bit of a smaller dose or maybe they had a metabolism that can detoxify this toxicity.”

Have plants and animals evolved?

Yes, both plants and animals have evolved over time to have this chemical trait for self-protection, Weng says.

Fireflies, for example, produce lucibufagins, chemical reactions similar to cardiac glycosides, to protect themselves against predators. Poisonous toads have bufadienolides, another chemical reaction to safeguard against predators.

“This all implies this really intricate chemical arms race between plants, insects and predators in a way that people cannot see,” he says. “It’s really through chemical communication in ways you can’t visualize. It’s really under the hood or or under the skin toxins that really protect these organisms.”

Arts & Entertainment

-

Why are fans upset about ‘The Last of Us’ season two? Experts say it tests the limits of fandom and parasocial relationships

Why are fans upset about ‘The Last of Us’ season two? Experts say it tests the limits of fandom and parasocial relationships -

In ‘Sinners,’ Michael B. Jordan plays identical twins, but what does the movie get right and wrong about these sibling relationships?

In ‘Sinners,’ Michael B. Jordan plays identical twins, but what does the movie get right and wrong about these sibling relationships? -

Pitch, Please! is winning a cappella competitions by ‘committing to weird things’

Pitch, Please! is winning a cappella competitions by ‘committing to weird things’