Northeastern engineers develop hybrid robot that balances strength and flexibility — and can screw in a lightbulb

How many robots does it take to screw in a lightbulb?

The answer is more complicated than you might think.

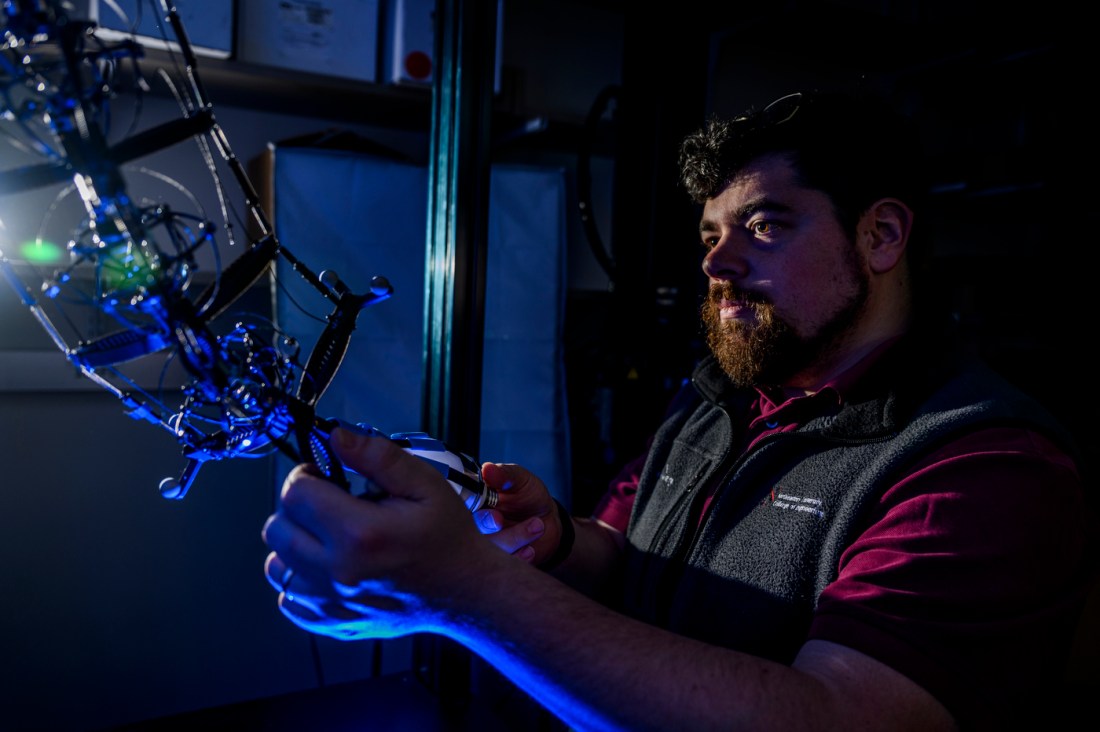

New research from Northeastern University upends the riddle by making a robot that is both flexible and sensitive enough to handle the lightbulb, and strong enough to apply the necessary torque.

“What we found is that by thinking about the bodies of robots and how we can make new materials for them, we can actually make a robot that has the benefits of both rigid and soft robots,” says Jeffrey Lipton, assistant professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at Northeastern.

“It’s flexible, extendable and compliant like an elephant trunk or octopus tentacle, but can also apply torques like a traditional industrial robot,” he adds.

Lipton explains that there are currently two types of robots in the world: rigid (or hard) robots and soft robots.

Rigid robots are your typical industrial robots. They start and stop automatically to perform precise tasks at great speed — and, often great danger — to humans.

“You like to put them behind cages because if they’re moving fast enough to be useful, they’re probably also moving fast enough to hurt you,” Lipton says.

These robots are great at spinning things, capable of applying torque at a distance, Lipton says.

Soft robots, meanwhile, are bioinspired — think an elephant trunk or an octopus tentacle — and can reach and pull and interact in complex environments and around people.

“If I have a robot that’s squishy like a pool noodle, it might slap me and it may sting a little bit, but it’s not going to break a bone,” Lipton says.

So what does this have to do with a lightbulb?

Well, a rigid machine has the necessary torque, but a soft robot has the maneuverability and flexibility to handle such a delicate task.

But in new research published in Science Robotics, Lipton has developed a hybrid hard and soft robot.

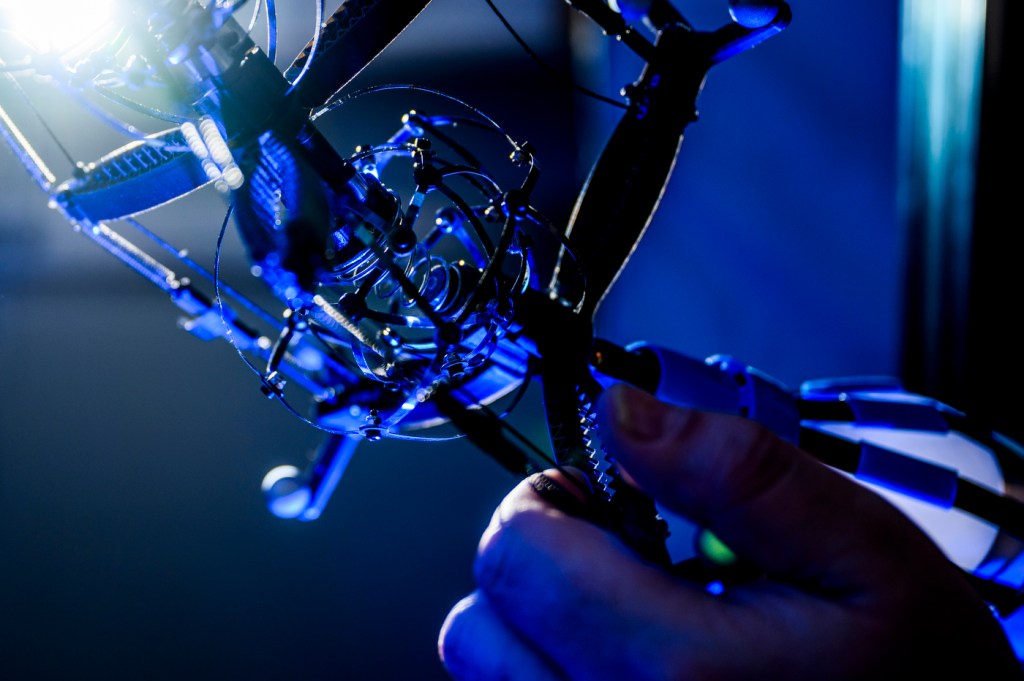

The hybrid robot works courtesy of a new material that works similar to the constant-velocity joints you find connecting a wheel to the axle of your car.

In a car, CV joints enable a wheel to move up and down and bounce around while keeping the axle in place, spinning, Lipton explains. But they are made of hard, rigid components.

“Ours, we can actually make soft and flexible and bendable,” Lipton says. “It’s a new type of joint, but you can pattern it and then you can make materials out of it.”

It’s a new approach to designing robots.

“It’s all by designing the shape, and that makes us really different from most soft robots where they’re focusing on changing the chemistry,” Lipton says.

The approach has led to a new type of robot arm — as well as a new answer to how many robots it takes to screw in a lightbulb.