Aboard Alvin submersible, Northeastern student maps hot springs 2,500 meters below the ocean’s surface

Hydrothermal vents fascinate researchers because they may “give us insights into how life may have evolved on our planet,” says Hanumant Singh, a Northeastern University professor of electrical and computer engineering.

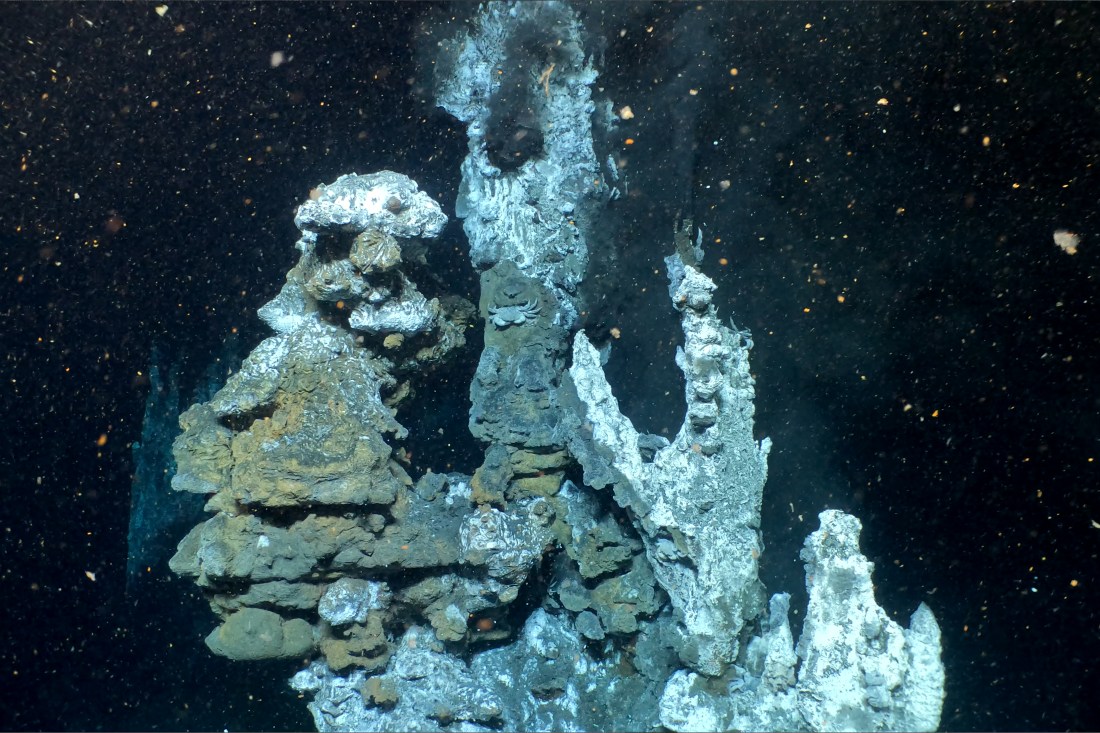

Deep below the ocean’s surface, a hydrothermal vent emits hot fluids that can reach over 798 degrees (370 degrees Celsius).

Bio9 is “a black smoker” about 2,500 meters — 1.5 miles — down along the seafloor of the Pacific Ocean, and an assortment of organisms reside along this vent, including vent zooplankton, vent shrimp, squat lobsters and Zoarcid fish.

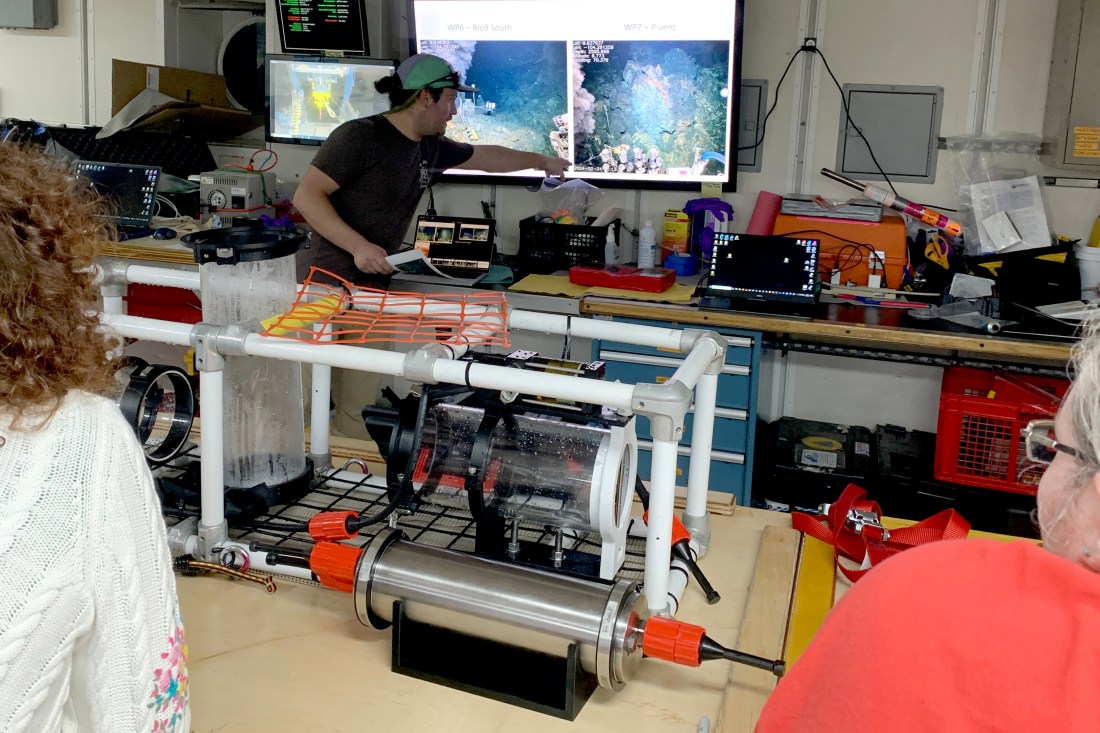

In January, Dennis Giaya, a Northeastern University doctoral student who works in the Field Robotics Lab, was aboard the submersible Alvin as part of an expedition to study hydrothermal vents in the East Pacific Rise, an area of strong volcanic activity located along the seafloor of the Pacific Ocean.

Attached to the vessel were two MISO 5K GoPro cameras recording video of Bio9 as it was emitting vent fluids that can reach nearly 800 degrees, Giaya says.

“The surrounding seawater is around [35 degrees, or 2 degrees Celsius], and fortunately for Alvin, the immense volume of surrounding seawater compared to the fluid exiting the vent means that the temperature rapidly drops off to only a few degrees above ambient as you get away from the vent orifice,” he says.

Giaya was on the journey with scientists who have been making multiple trips to the East Pacific Rise in recent years. These scientists are trying to predict when these sites may erupt and find out more information about how hydrothermal vents are connected under the Earth’s surface, Giaya says.

Giaya assisted in capturing videos and images. With the collected footage, Giaya created 3D models of the vent’s structure, which will be useful for geologists, geochemists and biologists who study both the deep ocean and how these structures change over time, he explains.

“Even something as simple as being able to say that the vent’s volume has changed by Y% from one year to the next can provide helpful context to some of the other data that are collected,” explains Giaya.

Hydrothermal vents were first discovered by scientists aboard Alvin while exploring an oceanic ridge near the Galapagos Islands, a volcanic archipelago in the eastern Pacific Ocean. The vents, hot springs formed as a result of underwater volcanic eruptions, have been a major area of focus since they were discovered in 1977.

Their discovery was monumental because the bacteria that live around the vents are chemosynthetic, which means they produce energy through chemical processes rather than through photosynthesis. It was the first time scientists observed that “life could exist independent of energy from the sun,” according to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Editor’s Picks

These hydrothermal vents fascinate researchers because they may “give us insights into how life may have evolved on our planet,” says Hanumant Singh, a Northeastern University professor of electrical and computer engineering and the director of the university’s Field Robotics Lab.

“There are one or two theories out there about how life may have evolved on our planet. One of them is that they evolved in shallow areas. Another is that they evolved from hydrothermal vents,” Singh says.

Hydrothermal vents also may help us get a better understanding of the core of our planet.

“Looking at these hydrothermal vents and how they have evolved is important to try to understand that plumbing and what’s going on,” Singh says.

It’s this type of research that is at the heart of the work Northeastern’s Field Robotics Lab does, explains Singh. In the past, the lab has worked with deep water archaeologists to explore ancient Roman and Phoenician shipwrecks and climate scientists studying glaciers in the Arctic.

“It’s true for all these applications that we are not subject matter experts, but we bring a unique set of skills to do very high resolution mapping and manipulation in areas that are very extreme.”

This mission was funded by the Marine Geology Geophysics Division of the National Science Foundation as part of a multi-year study to investigate magmatic and hydrothermal processes at the East Pacific Rise. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution vessels (RV) Atlantis, (HOV) Alvin, and (AUV) Sentry were used during the mission. The MISO GoPro cameras were developed in collaboration with the Multidisciplinary Instrumentation in Support of Oceanography Facility at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, DeepSea Power & Light and EP Oceanographic.