What is space junk and why does it pose an increasing risk for Earth? An expert explains the ins and outs

The amount of lingering “junk” in our air space is increasing so much that it could limit future space launches and impact Earth’s environment. An expert says we’re trying to find creative solutions to a global problem.

Year after year, humanity is setting new records for the amount of stuff we’re sending into the Earth’s orbit, spurred mostly by Starlink’s orbital domination. We’re getting more eyes (satellites) on the sky, but we’re also creating an increasing amount of space junk that has scientists on edge.

Space junk is anything that humanity has put into low Earth orbit that hasn’t either fallen back to the planet or spun out into space –– and there’s a lot of it.

Anncy Thresher, an assistant professor of public policy and philosophy at Northeastern University who specializes in space policy, says “99% of the stuff we’ve launched from Earth is sitting up there.” As commercial space launches led by Starlink and other private companies have become more common, the amount of stuff sitting in space has increased exponentially.

“We’re just getting more stuff up there and that increases the chances that junk is going to do something problematic,” Thresher says.

What problem does a bunch of material all the way in orbit pose to people on Earth?

For starters, there’s the possibility that it won’t stay in orbit. As space junk degrades over time, it can slow down enough that it starts to lower out of orbit and enter the Earth’s atmosphere, accelerating its fall. If an object is large enough, it won’t burn up in the atmosphere and instead plummet to Earth, as was the case when a half-ton piece of space junk landed in Kenya in January. Some researchers have even expressed concerns about the potential for space junk to hit planes.

Thresher says falling space junk will only become more of an issue, but it’s actually not the biggest risk posed by our growing orbital collection.

“We’re likely to see more of that sort of thing going forward with bigger pieces, but we’re pretty good at tracking the larger pieces so we at least get a warning when stuff comes down,” Thresher says.

The more serious threat is the space junk that stays up in low Earth orbit, not the objects that fall to Earth, she says. A worst-case scenario that becomes more likely year after year is what scientists call the Kessler syndrome. First proposed by NASA scientists Donald Kessler and Burton Cour-Palais in 1978, Kessler syndrome is a situation where an increase in low Earth orbit objects could lead to a chain reaction of collisions.

“The more collisions, the more fragments there are everywhere; the more fragments there are, the more likely you have collisions, which leads to this chain reaction event,” Thresher explains.

The risk is that as objects collide and break up, Earth’s air space will fill up with a wall of space junk that could shred anything we try to launch. That includes not only manned space missions but also the satellites that provide the backbone of modern communication.

Editor’s Picks

“The real worry there is that if you get enough junk up there and enough pieces flying off and sitting in orbit, it makes it very hard to launch other things because they’re going to get hit by the junk that’s up there,” Thresher says. “If you want to get to the moon, you’re going to have to pass through a barrier of space junk that we’ve built.”

“At the absolute extreme, it could even restrict our ability to move off planet unless we figure out a way to clean this stuff up,” she adds.

There is also another less discussed but just as significant risk posed by space junk: its environmental impact.

Space junk that burns up as it plummets to Earth is starting to pollute the atmosphere with metals and microplastics. One unintended consequence is that it is making the atmosphere more reflective, which not only makes life more difficult for astronomers looking into the cosmos but also could be impacting Earth’s temperature.

“It’s becoming more reflective because there’s more metal in it, which means we’re reflecting more sunlight,” Thresher says. “So, in a weird way, it’s cooling the planet, at an extreme.”

However, Thresher notes researchers are still trying to figure out how these atmospheric changes and unintentional geoengineering will affect the planet.

“There are real risks that we’re going to disrupt parts of the atmosphere and change a lot of stuff on Earth by accident,” she says.

How do we deal with space junk? It’s a question that various government entities, like NASA and the European Space Agency, along with companies like Starlink are starting to answer in creative ways.

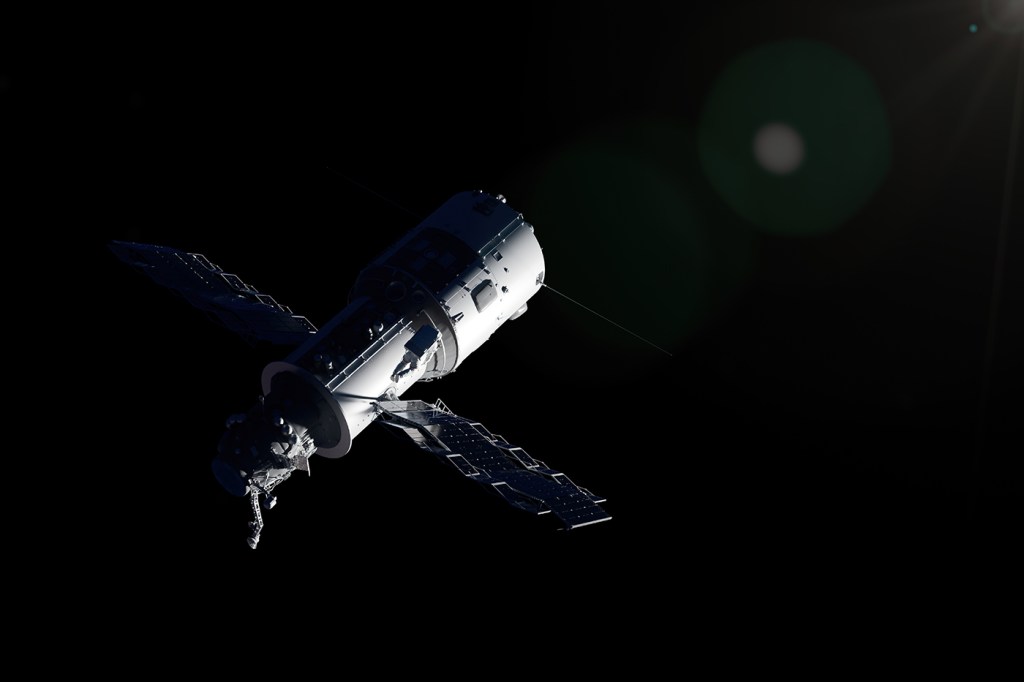

Every option is being explored, including lasers that would nudge debris enough to slow it down and even massive, satellite-launched nets that could bundle space junk. The issue has also spurred some movement toward renewable spacecraft: Japan successfully launched the world’s first wooden satellite in 2024.

However, Thresher says policy will likely have a role to play in controlling who and what can go into space, as terrestrial politics play out more and more off-planet.

“It’s definitely part of the conversation right now: What do we do to restrict this?” Thresher says. “I suspect we’ll start to see something like official regulations about who can put stuff in space because it is limited in terms of how much you can get up there.”