What is Jevons Paradox? And why it may — or may not — predict AI’s future

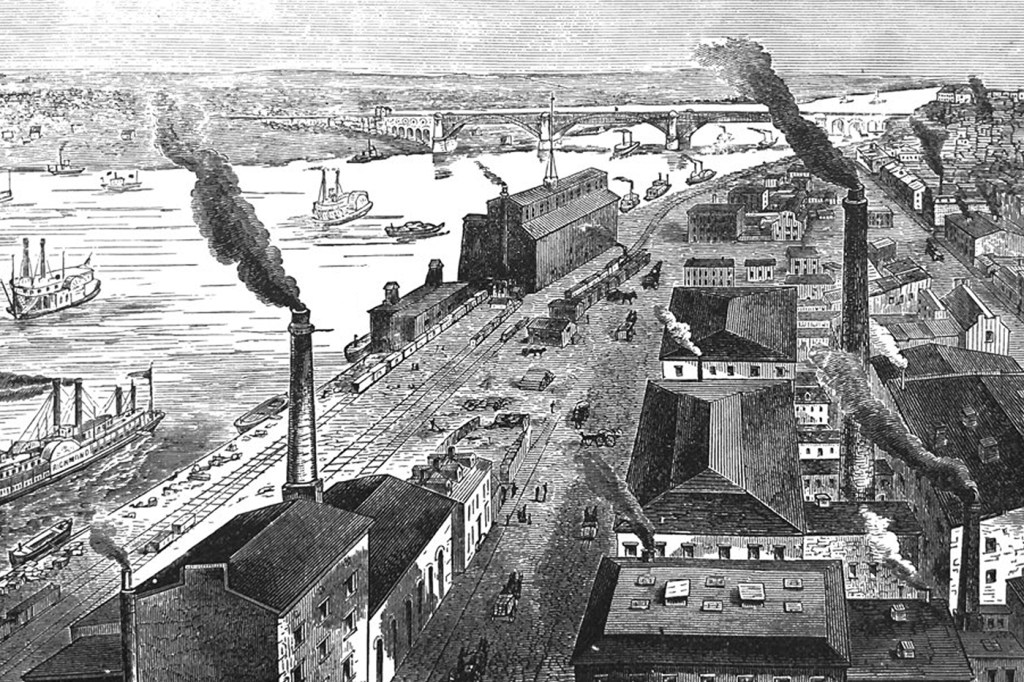

In 1865, William Stanley Jevons first described a paradox. He maintained that more efficient steam engines would not decrease the use of coal in British factories but would actually increase it. As the fossil fuel became cheaper, demand for the resource would grow, leading to the construction of more engines.

So, what does coal consumption in the 19th century have to do with today?

The technology sector hopes the answer is a lot, as entrepreneurs resurrect the paradox to buoy their projections for AI growth amid the emergence of a low-cost chatbot by Chinese startup DeepSeek.

“Jevons paradox strikes again!” Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella wrote on social media in the wake of the DeepSeek announcement. “As AI gets more efficient and accessible, we will see its use skyrocket, turning it into a commodity we just can’t get enough of.”

Northeastern University economics experts differ, however, on whether Jevons Paradox is the most appropriate analysis for the moment — or even the future — in artificial intelligence.

“There are a lot of things missing here,” says Madhavi Venkatesan, associate teaching professor of economics at Northeastern.

“When you really think about it, Jevons Paradox says that efficiency with respect to the use of a limited resource will lead to its elimination due to demand effects. … But I don’t see that increasing efficiency in AI is being tied to the elimination of resources used as inputs — though it should be; the focus is only on the increase in the demand for AI.”

Richeng Piao, a visiting lecturer of economics, has a different take.

“Jevons Paradox teaches us that efficiency unlocks new demand,” Piao explains. “AI’s democratization will drive GPU sales, energy use and (chipmaker) Nvidia’s market power.”

What is Jevons Paradox?

British economist William Stanley Jevons first presented his eponymous paradox in his 1865 book, “The Coal Question,” where he noted that more efficient steam engines had not led to a decrease in the use of coal in British factories as many believed, but increased the use as the fossil fuel became cheaper and more engines and factories were built.

“Efficiency can backfire by making a resource so cheap that everyone uses it more,” Piao summarizes, noting that British coal consumption tripled by 1900.

The paradox applies to various technological shifts. For example, Los Angeles had 10,000 horses in 1900, but by 1950, there were 1 million cars, Piao notes. Similarly, despite the rise of fuel-efficient and electric vehicles, total miles driven has increased, and energy-efficient computers have led to widespread smartphone use and data centers that now consume 1.5% of global electricity.

The unveiling of DeepSeek

With the recent unveiling of Chinese startup DeepSeek’s AI chatbot — developed for just $5.6 million in computing costs compared to OpenAI’s latest chatbot, which cost around $100 million — investors initially panicked. However, their reaction has since shifted to a more measured “wait-and-see” attitude or even optimism.

Editor’s Picks

Jevons Paradox seems to apply, Piao says. He sees AI becoming accessible to startups, schools and small businesses, thereby expanding the market and, in turn, increasing — not lessening — energy demand and AI use.

“Even with efficient models, AI’s complexity is growing exponentially,” Piao says. “As AI becomes a commodity, industries will compete to build proprietary systems, driving 20% of U.S. electricity demand by 2030.”

“Jevons’ idea feels relevant today,” Piao says. “We keep making tech greener and faster, but humanity just … does more of it. AI could follow the same path.”

But wait, hold on a second

However, Venkatesan points out that it’s not a perfect comparison. She explains that DeepSeek emerged because a key resource — Nvidia computer chips — became severely limited by legislation before their use could expand exponentially.

More importantly, Venkatesan — who studies economic sustainability and markets — argues that a theory based on 160-year-old markets doesn’t really apply today.

“The problem with this is that they didn’t have economies like today where the externalities — the non-monetary components of our daily actions — are so obvious,” Venkatesan says. “Today we have a larger population, we deal with synthetic products, so it’s not really smart to think of just the cost to manufacture something.”

Venkatesan notes that the cost of developing AI doesn’t account for the fact that the computers used contain toxic materials, aren’t designed for recycling, and lack a sustainable method for disposal.

And technology is moving so fast that some externalities — for example, our ability to navigate without a GPS or to research without using Google — are not even considered, she adds.

“It’s not about the product and pricing and efficiency and jobs, but the subsidization of those things with our health, well-being and what we consider normal behavior in human societies because none of those things are accounted for,” Venkatesan says.

Instead of Jevons Paradox, Venkatesan sees the future of AI through the lens of creating needs out of wants.

For example, cellphones were initially very expensive, limiting their use.

But now not only are they ubiquitous, Venkatesan says, “we can’t even call someone without our cellphone because we don’t know their phone number.”

A breakfast table issue?

Philip Hanser, an economics lecturer at Northeastern, meanwhile, suggests it’s premature to determine whether Jevons Paradox is at play.

First, he notes that it is much more energy-intensive to train and develop an AI model — where DeepSeek says it achieved its energy savings — than it is for a user to query one.

“You’re going to use up some of that improved energy efficiency of DeepSeek in higher usage, no matter what,” Hanser says. “But the question becomes, is that large enough to completely offset the savings between the two models? I don’t know.”

Like Venkatesan, Hanser applies an alternate economic theory: the idea of complementary goods versus substitute goods.

“A substitute good would be something like oat milk for regular milk; a complementary good would be something like eggs and toast,” Hanser says. “If it’s a complementary good, then AI becomes an assistant to me. If it’s a substitute good, then whatever I was doing the AI does instead of me.”

Hanser says he doesn’t know which use will predominate. But it could determine whether AI and its energy use will exhibit Jevons Paradox or not.

“If it’s a substitute good, my guess is that you use up all of the energy efficiency,” Hanser continues. “If it’s a complementary good, my guess is you may not.”