Jan. 6 and QAnon have their roots in gaming, Northeastern professor concludes in new book

From alternate reality games to the Jan. 6 riots, Celia Pearce looks at the idea of “play” and how the American far-right has weaponized gaming and online communities for its own gain.

It’s common for children to learn what happens when playing around with friends gets out of hand. Usually it means someone taking a game a little too seriously, breaking the rules or hurting someone else’s feelings, and the consequences end with knees scraped, tears shed and, hopefully, a lesson learned.

But what happens when “play” gets truly out of hand?

According to Celia Pearce, a professor of game design at Northeastern University, you need to look no further than the Jan. 6, 2021, riots that shook the Capitol and the nation.

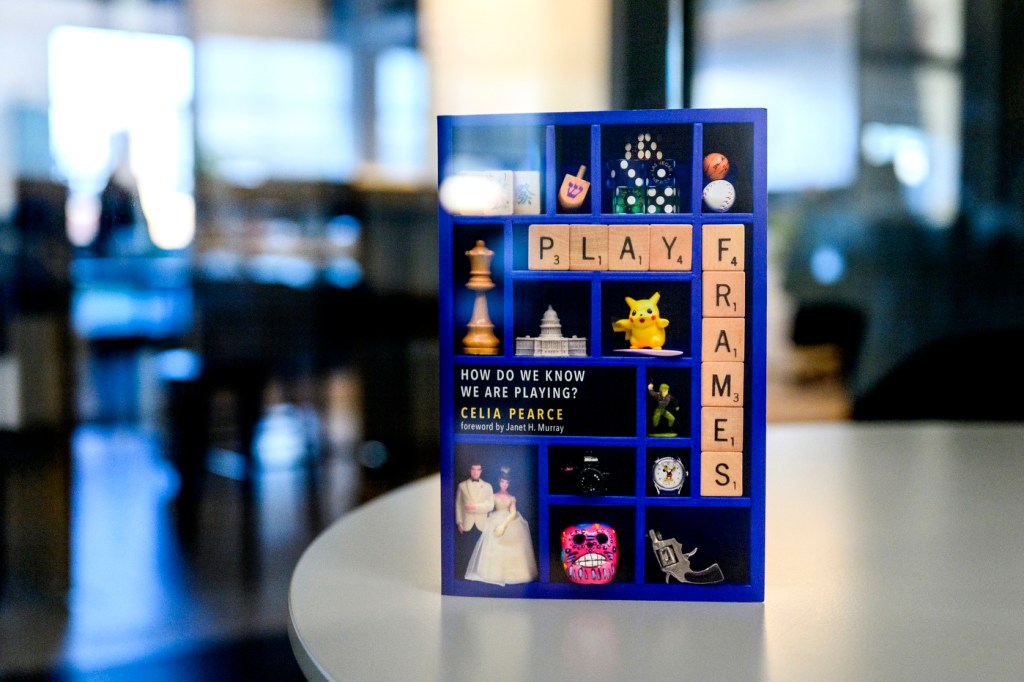

In her new book, “Playframes,” Pearce traces the roots of Jan. 6, the QAnon conspiracy theory and the modern American far right back to the world of gaming to show what happens when the boundary between “play” and real life gets blurred –– and dangerous.

Pearce, who will take a deep dive into her new book during a launch event at Northeastern on Jan. 21, covers a lot of ground culturally and politically but connects it all to the idea of the “playframe.” Whether you’re playing a sport or video game there is information, both explicit and implicit, that we are playing. There are rules to a game that we learn and know by heart. There are specific locations we go to play. There might even be clothing or accessories –– a sports jersey or gaming headset –– that we wear when playing.

All this information is the frame that tells us we’re playing, which is important because when we’re playing, some of the rules that usually govern our society go out the window.

“[The players and] the audience at Fenway Park are in a sort of playframe,” Pearce says. “They can do really weird stuff that if they did anywhere else in the world, they would be seen as insane. But because they’re sports fans in a sports fan frame and they’re in a sports fan place, they can behave in radically different ways than is socially acceptable elsewhere.”

But sometimes there are “fuzzy areas that exist in the play sphere,” Pearce says, and it’s here that the exceptional behavior in a game might start to make its way into other areas of life where the consequences of “play” are very real, like politics.

In connecting the dots between Jan. 6 and gaming, Pearce begins with alternate reality games in the early 2000s, a medium that by design blurs the boundaries between a playframe and what lies outside the frame.

Players of early ARGs would receive emails and text messages that might task them with going to a real-world location where they would find a URL that would send them to a fake website and further down the rabbit hole of a narrative that stretched from the internet to the physical world and back again.

Notably, they were often designed to tell a conspiracy-laden story that had players solving puzzles and looking for clues in every part of their lives. It’s an instantly appealing concept but one that even the designers of these games realized early on could be used for darker purposes.

Pearce says that fear has been borne out in QAnon, a far-right conspiracy theory based on false claims from the anonymous figure known simply as Q that there is a cabal of powerful cannibalistic child molesters operating a global sex trafficking ring that is aligned against President-elect Donald Trump.

As the theory spread across various corners of the internet, Q regularly used the phrase “This is not a game,” which was the slogan for ARGs. Based on her research, Pearce says this is not a coincidence. In the ARG community, it was part of the playframe, a way of referencing the boundary-pushing nature of ARGs. But taken out of that frame and placed into another, it becomes a dangerous way to bolster Q’s false claims while playing into the mindset of the online ARG community.

“At the very least, people who were building on the conspiracy recruited players out of these … types of forums because they knew they were problem solvers and they knew would try to weave a narrative around all of these ‘clues,’” Pearce says. “In a sense, they gamified a real-world conspiracy theory by appropriating the phrasing and the culture of that.”

Pearce adds that others have also figured out how to misalign the playframe to take advantage of how gaming communities think and behave. Steve Bannon, Trump’s former adviser and chief strategist, used to operate a company that paid low-wage workers to harvest virtual currency in games like “World of Warcraft.”

Editor’s Picks

“While he was working in that space, he thought it was very interesting that this ongoing white male rage seemed to be pervasive throughout gaming communities,” Pearce says. “In his biography he said that this is what inspired him to harness this rage and point it in the direction of politics.”

Pearce adds that it was particularly easy to push and harness these ideas and emotions outside of the online gaming community playframe because they “were coexisting on the same platforms” where broader social and political conversations were happening, like Twitter.

The most toxic elements of gaming culture, which manifested explicitly in the mid-2010s harassment campaign known as Gamergate, have breached one frame and entered another: Gamergate has been labeled “the canary in the coalmine for Trump’s first election,” Pearce says.

With both QAnon and Bannon, the playframe is misaligned, but it’s not just happening by accident. There is a purpose behind it, Pearce says, and it’s here that she sees the connections to Jan. 6.

“Why is this person dressed up as a Viking while they’re attacking the nation’s capital?,” Pearce says. “When you start to think about it this way, it becomes less shocking that people were rioting in the Capitol in costumes. You begin to understand that there is this very loose membrane between people who think they’re playing a LARP [live action roleplay] and an ARG and people who are committing very real acts of violence. … When you add the misalignment of the playframe along with deliberate deception, you have a recipe for disaster and that’s where we are right now.”