How US policies and perceptions impact Puerto Rico’s energy infrastructure

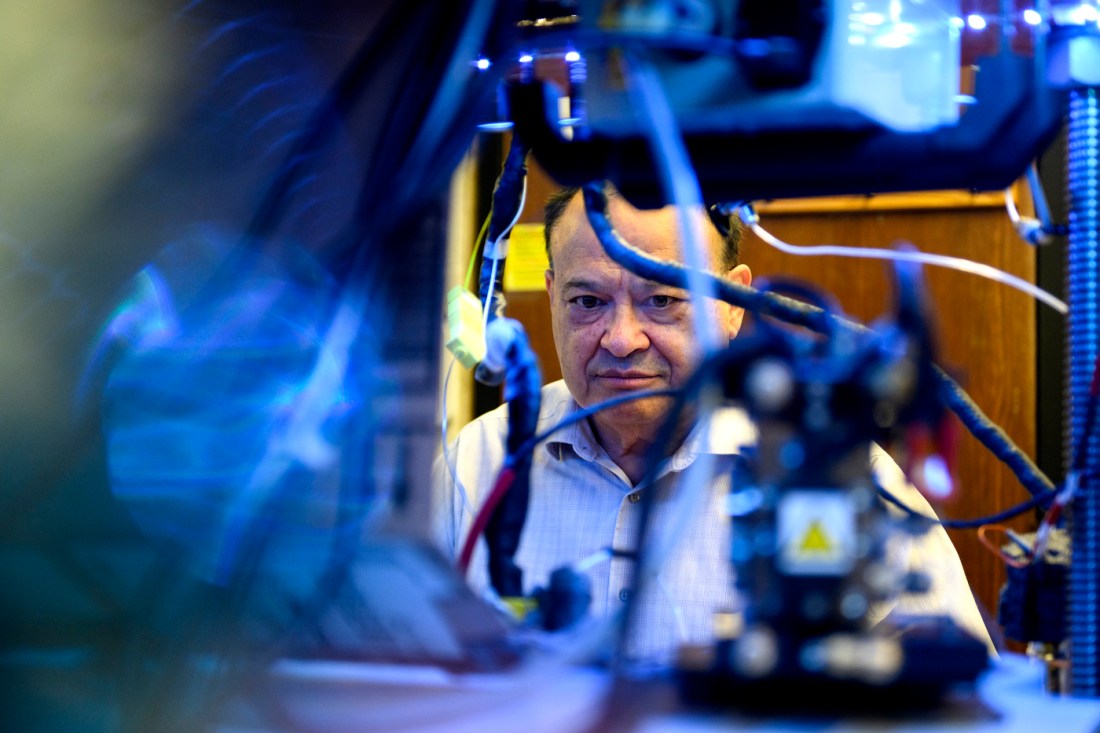

Tuesday’s blackout was not an anomaly as Puerto Rico has been plagued by power outage issues for years, says Northeastern professor Eugene Smotkin, who specializes in studying materials used for clean energy.

Northeastern University chemistry professor Eugene Smotkin was in his home in the Puerto Rican residential district of Old San Juan when he, like more than a million other residents on the island, lost power on New Year’s Eve.

He and his wife first noticed the power went out when the ceiling fan above their bed stopped.

Smotkin considers himself among the more fortunate — his power was restored later that afternoon. Other less tourist-centric areas were hit harder by the outage and it caused headaches for many preparing for celebrations.

“This became a mess for Puerto Ricans in general,” he says. “We didn’t know if we were going to have power on New Year’s Day.”

Nearly all residents have had their power restored, according to Luma Energy, the private Canadian power company that manages and operates the territory’s electrical grid. Rolling blackouts likely will occur as the system is fully brought back online.

Blackout not an anomaly

But Tuesday’s blackout was not an anomaly as Puerto Rico has been plagued by power outage issues for years, explains Smotkin, who specializes in studying materials used for clean energy and was featured in an award-winning Northeastern Films documentary on bringing renewable energy sources to Puerto Rico.

“We’ve had a power failure every week for the past few months,” Smotkin says, highlighting that much of the territory’s electrical grid equipment is more than 40 years old and continues to be crippled by storms like Hurricane Maria in 2017 and Hurricane Ernie in 2024.

“As a result, the grid remains highly vulnerable, with power failures occurring frequently — even in San Juan, the capital city,” he says.

While the cause of the most recent outage is still under investigation, Luma officials say preliminary findings suggest that a faulty underground electric line located in the south of the island may be to blame, according to the Associated Press.

Smotkin says many of Puerto Rico’s electrical issues come down to its place in the eyes of the United States.

Perception on U.S. mainland

“We need to modify the perception of what Puerto Rico is among U.S. citizens,” Smotkin says. “It is an unincorporated territory, and there’s huge misperception among the U.S. citizens about who we are and what the status of Puerto Rico is.”

Laura Kuhl, a Northeastern professor of public policy and urban affairs and international affairs, has spent much of her career studying Puerto Rico’s climate and energy infrastructure.

She echoes Smotkin’s sentiment.

“One of my big picture takeaways coming out of this power outage is that it’s impossible to understand anything about energy policy in Puerto Rico without acknowledging how much of its colonial relationship impacts all decision-making and all aspects of daily life,” she says.

Puerto Rico — which has been in a significant debt crisis for years — does not have legal options that states or municipalities have to file for bankruptcy or restructure debt to manage public utilities, she adds.

Instead, Puerto Rico has the Financial Oversight & Management Board, a federal body composed of outside authorities — not elected by residents of the territory — that is charged with approving Puerto Rico’s budget. For years, because of Puerto Rico’s high poverty rates and non-revenue-generating electrical service, the territory was unable to afford maintenance of the grid, Kuhl explains.

Decision to privatize the grid

After Hurricane Maria devastated the territory in 2017, a decision was made to privatize the electrical grid in hopes of improving services. In 2021, Luma Energy was hired for the job, but the grid continues to be unreliable.

“The hope was that this would generate more economic efficiencies in the running of the grid, but that has not been what Puertro Ricans have experienced. Outages continue to be very common,” Kuhl says.

Puerto Rico’s electrical grid is a very centralized top-down system, Kuhl says, making it particularly vulnerable if even one part of the system goes down. Add this on top of years of a lack of investment to properly maintain the grid, and frequent power outages are not surprising.

Featured Posts

“In contrast, if Puerto Rico had, for example, a lot of renewable energy sources where the generation was more distributed, even individual outages wouldn’t have those widespread repercussions,” Kuhl says.

In 2019, Puerto Rico passed a major energy law with the goal of becoming 100% energy renewable by 2050. As of 2025, only 7% of the grid uses renewable energy, according to Kuhl.

New Puerto Rican Gov. Jenniffer González Colón says an energy czar will be hired to oversee the situation and her administration is looking to replace Luma. She is also calling for the rollback of some of the clean energy targets and instead investing more in natural gas.

Funding from FEMA

Another major issue is Puerto Rico has to improve the electrical grid, but funding from the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency is restricted and can only be used for maintenance and not for upgrades, Smotkin says.

The territory’s electrical issues are made even more difficult by the Jones Act, a law passed in 1920 requiring that cargo, including oil, must be transported between U.S. ports on U.S. vessels, according to Smotkin.

“Any fuel that we purchase must go on a merchant marine ship, which inflates the price,” says Smotkin. “This sort of creates a monopoly that the United States has in Puerto Rico. … We’re paying more money for energy — 23.77 cents per kilowatt hour. That’s 41% higher than what people pay in the (mainland) U.S.”