Why are axolotls suddenly so popular — and going extinct at the same time?

Northeastern University professors explain how the axolotl — an adorable amphibian with a permanent smile and pink, feathery gills — has become so popular, and why it’s also critically endangered in the wild.

You may have seen axolotls — an amphibian in the salamander family with a permanent smile and pink, feathery gills — in a pet store or as a plushie in a window, but the endearing animal’s popularity seems to be rising just as it has become critically endangered in the wild.

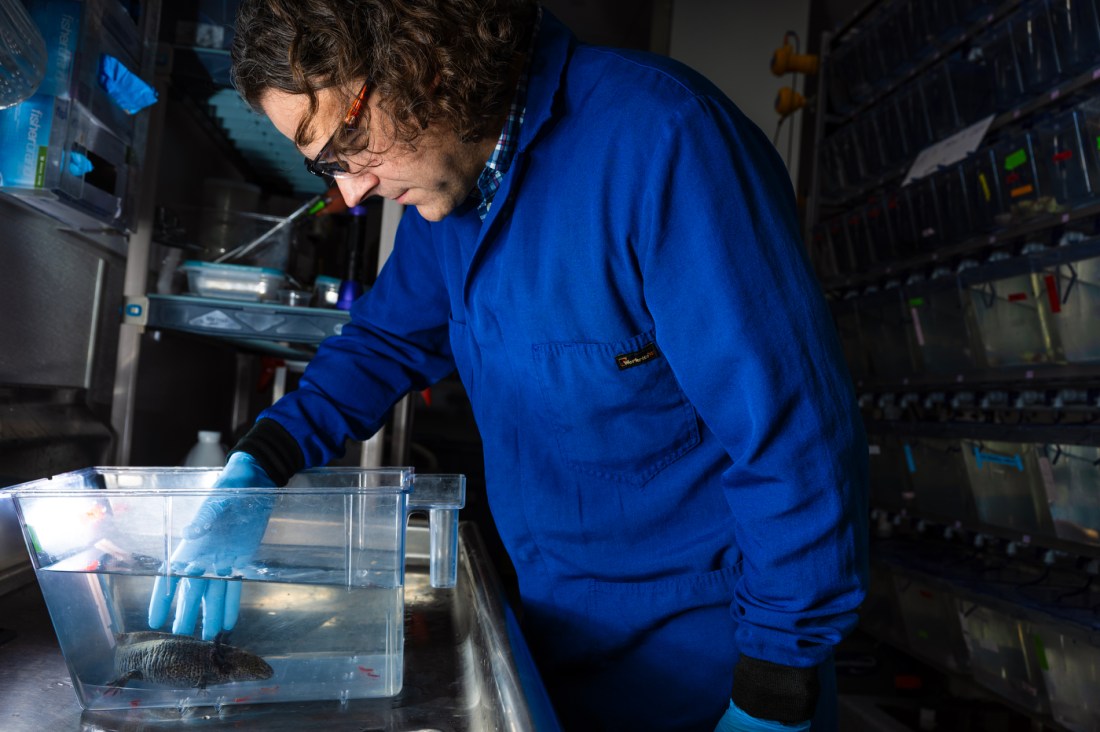

James Monaghan, professor of biology at Northeastern University, specializes in the friendly looking critters, studying their amazing regenerative capabilities. “Axolotls have just exploded in [popularity] the past couple of years,” he says.

Monaghan began working with axolotls on the first day of his Ph.D. program. Back then, “no one knew in the general public what an axolotl was, so I’d have to explain,” he says.

That’s changed radically over the past 20 years, he continues. “Now I just can say, ‘Oh, I work on axolotls,’ and everyone just lights up.”

Axolotls have become especially prevalent in youth culture, partly because younger people find them “incredibly cute,” Monaghan says. “They’re pink, they have feathers,” but aren’t birds.

“They don’t really have feathers,” he says with a laugh, “but their gills are feathery. They have a constant little smile on their face. If you were to create a cute animal that you couldn’t think existed naturally, it’s kind of the axolotl.

“It’s got the vibes of a dragon, but a nice dragon.”

How to train your axolotl

Monaghan notes that the axolotl is “entrenched in Mexican culture. It’s named after an Aztec god, Xolotl.”

So how did an amphibian found in one lake outside Mexico City take the world by storm?

Alexandra To, a Northeastern assistant professor of computer science, says that axolotls suddenly entered public consciousness with their 2021 appearance in Minecraft — the first video game to sell over 300 million copies.

“Minecraft is enormously popular for young players,” To says. The game “allows for social play, exploration, sandbox style play where you can make anything.”

The inclusion of the axolotl appealed to the game’s primary audience of young players, who find in the game a “space for transformation,” To continues. Minecraft provides players “great intrinsic motivation to discover more about any new elements that are added to the game.”

This motivation could come from the simple joy of exploration, or, as To says her own partner did, in embarking on a project to create “an enormous zoo with every in-world animal.”

Monaghan also thinks that children’s animation has had something to do with the rise of the axolotl’s stardom.

“I don’t know if it’s actually the motivation for ‘How To Train Your Dragon,’” he says, but notes that the one of the main dragon characters in that film — named “Toothless” — has some suspicious similarities to the axolotl, from its endearing smile to the shape of its ears, which connote the axolotl’s feathered gills.

Beyond how cute they are, the axolotl boasts an impressive array of health mechanisms, of which their ability to regrow limbs is only the beginning.

From scientific oddity to critical specimen

Axolotls’ (somewhat limited) initial fame came from their ability to regrow entire limbs after serious injury — Monaghan and his lab have discovered that they are also capable of regenerating a “large portion or their lung.” Axolotls are notoriously resistant to cancers, “never get infections after an injury,” he says and can live for 20 years, which may be another factor in their appeal to the commercial pet market.

In fact, Monaghan says, axolotls are “the longest standing lab animal of any animal, longer than flies, longer than worms, longer than mice.”

The first scientific specimens were collected in 1864, Monaghan continues, from a canal system in and around Lake Xochimilco, outside Mexico City. Lake Xochimilco is the only place they are still found in the wild.

First collected as an oddity — they look remarkably different from other salamanders and live their entire lives in water, unlike most amphibians — over time, the axolotl proved a valuable lab specimen, especially hearty under the right conditions and able to breed year-round.

Editor’s Picks

Before long, scientists were exploring the axolotl genome to unlock their regenerative abilities.

With the rise of CRISPR, “you can manipulate genes, and ask what genes are important for regeneration,” Monaghan says. “It’s really led to this renaissance of regeneration research.”

The entire stock of modern axolotls found in today’s laboratory settings — and in pet shops around the world — is descended from that original population collected in 1864, with only occasional introductions of new genetic material into the line, Monaghan says.

The white axolotl, which seems to be “pretty much every stuffed animal that’s out there,” is “actually a mutation of a single animal that was collected in 1864.”

“You can get color variants, but the pink variety — that’s from one founding animal.”

Meanwhile, the wild population of axolotls is steadily vanishing.

“Maybe up to the 1950s, you could put a net in Lake Xochimilco, the canal system, and pull up adult axolotls. And then every decade since, it’s just crashed,” Monaghan says. “To the point now that they’re critically endangered, and it takes weeks to even find one.”

Monaghan points to climate change and pollution as two of the primary factors. “Being an amphibian, you’re at the [whim] of your environment. You’re taking in everything through your water.”

Axolotls are also very sensitive to the temperature of the water they live in; as global temperature rises, it becomes more and more difficult for them to survive.

Additionally, the expansion of Mexico City and the introduction of invasive species, which can consume vulnerable axolotl eggs, has led to the loss of viable habitats in and around Lake Xochimilco.

Saving the axolotl

But if axolotls are so widely available in both commercial pet stores and laboratory environments, why not simply reintroduce them to the wild?

Monaghan says it’s not that simple.

The population used by scientists, from that original 1864 stock, has been evolving as its own distinct line for 150 years, selectively bred to be better and better scientific specimens, distancing this population from their wild forebears.

“It’s probably not the best strategy to take a species that’s been inbred since 1864 and reintroduce it into its natural habitat,” Monaghan says.

“We can’t take the current axolotl and put it into the environment in Mexico City and expect them to thrive the same way as the original collection in 1864. The environment’s changed, but the animals themselves have changed.”

But there are efforts to save the wild axolotl, driven through building public awareness.

Mojang, the company that makes Minecraft, “has been pretty transparent about conservation as one of their core values,” To says. “The inclusion of axolotls and their in-game rareness mirroring their real-world endangered status is a fantastic example of how game mechanics can reinforce educational messages.”

All the publicity seems to be a good thing; greater awareness hopefully means greater support for conservation efforts. Monaghan serves on the advisory board of the Ambystoma Genetic Stock Center, which provides “information on the axolotl as a lab animal, but also as a species.” he says. “Those direct efforts could really go a long way [toward] saving the axolotl.”

“All of a sudden,” he says, the axolotl “seems to be absolutely everywhere.”