What’s next for the ‘special relationship’ between the US and UK in the second Trump presidency?

Northeastern political experts Josephine Harmon and John Ackerman analyze whether the close trans-Atlantic alliance will survive the next four years.

LONDON — Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher were seen as political soulmates. George Bush regarded Tony Blair as America’s staunchest ally. Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt had a friendship that helped the Allies secure victory in World War II.

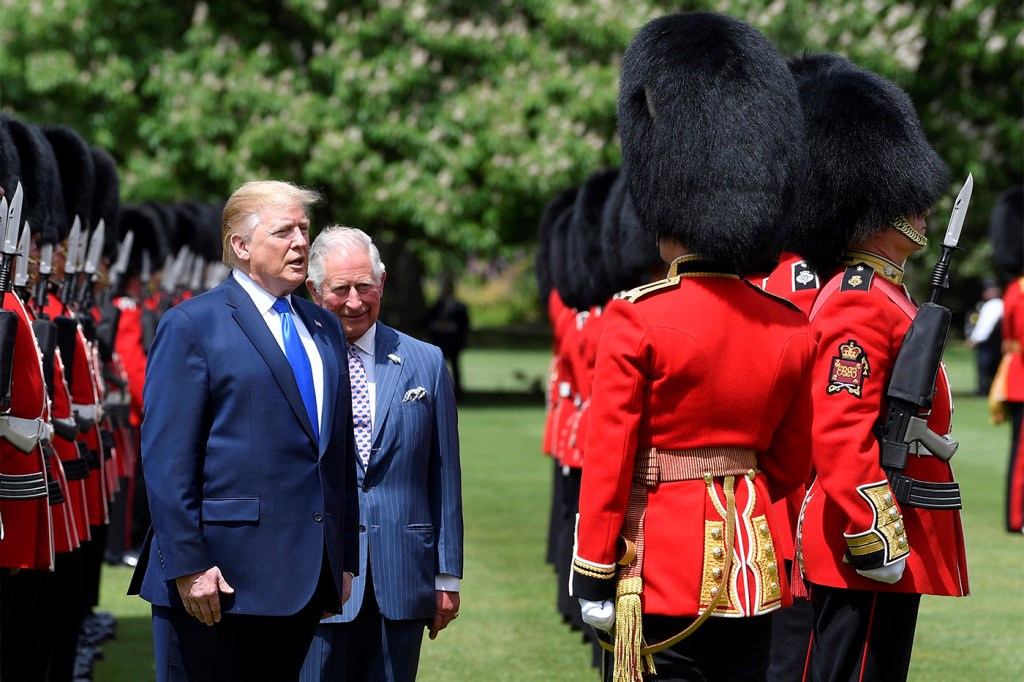

So what is next for the United States and the United Kingdom’s so-called “special relationship” with a second Donald Trump presidential term due to start in the new year?

Editor’s Picks

Will British Prime Minister Keir Starmer, whose Labour Party won a landslide election in July, be able to boast as close a relationship with his respective White House incumbent as his predecessors had?

Josephine Harmon, an assistant professor in political science at Northeastern University in London, says it is in Starmer and the U.K.’s economic interests for strong ties with Washington to continue.

“The special relationship is more special to the British than it is to the Americans,” Harmon says.

“Everybody thinks they have a special relationship with America. But it is that much more important for Britain as a mid-sized economy that is not doing as well, relative to how the U.S. is, in terms of growth and now being outside of the [European Union’s] single market.”

Outspoken on tariffs

Trump, Harmon points out, has been outspoken on applying tariffs on European goods coming into America in retaliation for the trade deficit the continent has with the U.S. Harmon says such a punitive action could particularly hurt the U.K., given that Brexit has already made trade more difficult with European Union members that make up its largest market.

“Trump has indicated he wants to slap at least 10% tariffs on European exports, which presumably he would do to the U.K. as well,” she continues.

“That would wipe off at least 1% of GDP (gross domestic product), which would be awful given that the Treasury needs to increase tax revenue and generally has promised economic growth as a solution to the country’s problems. That tariff policy would be a real problem, so there is a need for Starmer’s Labour Party to ingratiate themselves with the Trump administration.”

Labour was in opposition when Trump was last in the Oval Office and was led by left-wing politician and U.S. critic Jeremy Corbyn (he has since been expelled from the party by Starmer for his response to an anti-semitism investigation).

It was in that environment that David Lammy, the now-foreign secretary in Britain, penned an article labeling Trump as “a woman-hating, neo-Nazi-sympathising sociopath.” In comments he has looked to distance himself from since Trump’s victory over Kamala Harris, Lammy said the billionaire was “deluded, dishonest, xenophobic, narcissistic” and “no friend of Britain.”

May be looking to mend bridges

Starmer may have been looking to mend bridges swiftly when he became one of the first leaders of a major economy to congratulate the 78-year-old Trump on his Nov. 5 win. In his first conversation with the president-elect the day after the vote, Downing Street said the prime minister offered his “hearty congratulations” and vowed that the U.K.-U.S. relationship would “continue to thrive.”

Harmon says that Lammy’s previous comments should not necessarily prevent him or Labour from developing a cordial relationship with the Trump administration, highlighting that the Republican has shown he can forgive and forget.

“The obvious example is JD Vance, who is now VP in waiting and who had very strong words that were very similar to the ones that Lammy came out with [Vance previously said Trump was ‘reprehensible’ before becoming a supporter]. I think it is possible to elicit a positive response from Trump after having made negative comments — but there’ll be a lot of reverse ferreting to do.”

As much as Britain may want the special relationship to continue, U.S. voters may have other ideas, says John Ackerman, an assistant professor in politics and international relations on Northeastern’s London campus.

Trump’s isolationist perspective

In putting Trump back in the White House, with his “isolationist perspective” when it comes to world affairs, Ackerman says the majority of American voters may be questioning whether they want traditional international ties like the U.K.-U.S. special relationship to remain.

“The so-called special relationship is what we might think of as the foreign policy ‘establishment’ — something pursued by successive governments and presidents,” says Ackerman, a New Jersey native who has been living in the U.K. for the past decade.

“I think that those kinds of establishment views are part of what is being called into question more broadly.”

Ackerman says that, while international relations was certainly not the main issue on the ballot during the presidential election, it likely factored into a wider feeling among Trump supporters that the “political and economic system is failing way too many Americans.”

“That leads people to turn inward and away from the rest of the world,” Ackerman says, “and to worry about themselves, right? They feel, with some justification, that money is being spent elsewhere to help others while they themselves are getting a raw deal.

“There is an exhaustion among the American public, I think, with involvement in overseas wars, adventures and conflicts. And Trump has managed to sell himself as a peacemaker who says he is going to get Americans out of these foreign entanglements.

“I think people were voting more on other issues, but I do think that he had some success in selling himself as the one who was going to get America out of its problems abroad too.”

Allies have been war-gaming

Allies like Britain have been war-gaming what a Trump presidency would mean for future Western military and financial support for Ukraine in its battle against invading Russian troops, along with stability in the Middle East.

Ackerman and Harmon are both of the view that the U.K. will want to keep up its end of the “special relationship” bargain during another four years of a Trump presidency. But Ackerman says that risks are inherent in any strategy that looks to woo a leader as unpredictable as Trump.

Former Conservative Prime Minister Theresa May was keen to work on securing a landmark post-Brexit trade deal with the U.S. after Trump’s first victory in 2016 but the news headlines focused far more on the awkward hand-holding the pair engaged in than any new economic pacts.

“Everybody’s going to have to work with Trump,” Ackerman continues. “But there is room to embarrass oneself and just come away looking weaker and coming away harmed by the efforts to curry favor with him. And I think that’s something that the U.K. government should be careful about.”