Northeastern researchers create plastic that dissolves in water that promises to combat global pollution crisis

At a time when synthetic plastic has polluted nearly every corner of the globe and appeared in food and in the human body, Northeastern University researchers have developed a new plastic that dissolves in water.

“The kind of impact that human-made materials are making on the living world is resulting in climate change, pollution and more,” says Avinash Manjula-Basavanna, a senior research scientist at Northeastern University. “One of the ways that we are able to address this is to make materials sustainable and also make materials which are smart or intelligent.”

Manjula-Basavanna and Neel S. Joshi, associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Northeastern, call their bioplastic MECHS — an acronym for Mechanical Engineered Living Materials with Compostability, Healability and Scalability.

The researchers presented their discovery in a paper published in the journal Nature Communications.

The study showcases the researchers’ most recent work with engineered living materials, which use living cells to produce functional materials.

Manjula-Basavanna and Joshi explain that such materials have notable assets.

First, the nature-inspired solutions can be made to regenerate, regulate and/or respond to external stimuli such as light and can even heal itself.

Featured Posts

Secondly, unlike the plastics that are polluting the planet and our bodies, the materials are biodegradable in water and even the compost bin.

“Right now we use a lot of conventional nonbiodegradable plastics for applications they don’t need to be used in at all,” Joshi says. “If we replace that with our plastic, you could just flush it down the toilet and it would biodegrade.”

But while engineered living materials have been manipulated to adhere, catalyze and remediate, and be either soft or stiff, such materials have not been scalable for widespread production.

That’s where MECHS comes in.

MECHS consists of engineered E. coli bacteria with a fiber matrix to create a paper- or film-like material.

The fibers give MECHS several desirable properties. It means that MECHS can stretch like plastic wrap, can be genetically engineered by adding proteins or peptides to make it more or less stiff. And it is healable — a small amount of water disentangles the fibers, which then re-entangle as the MECHS dries.

Meanwhile, a lot of water or a trip to a compost bin causes the material to dissolve. In fact it dissolves much faster than other biodegradable plastics, the researchers found.

Finally, the material can also be easily mass produced in a process similar to paper manufacturing.

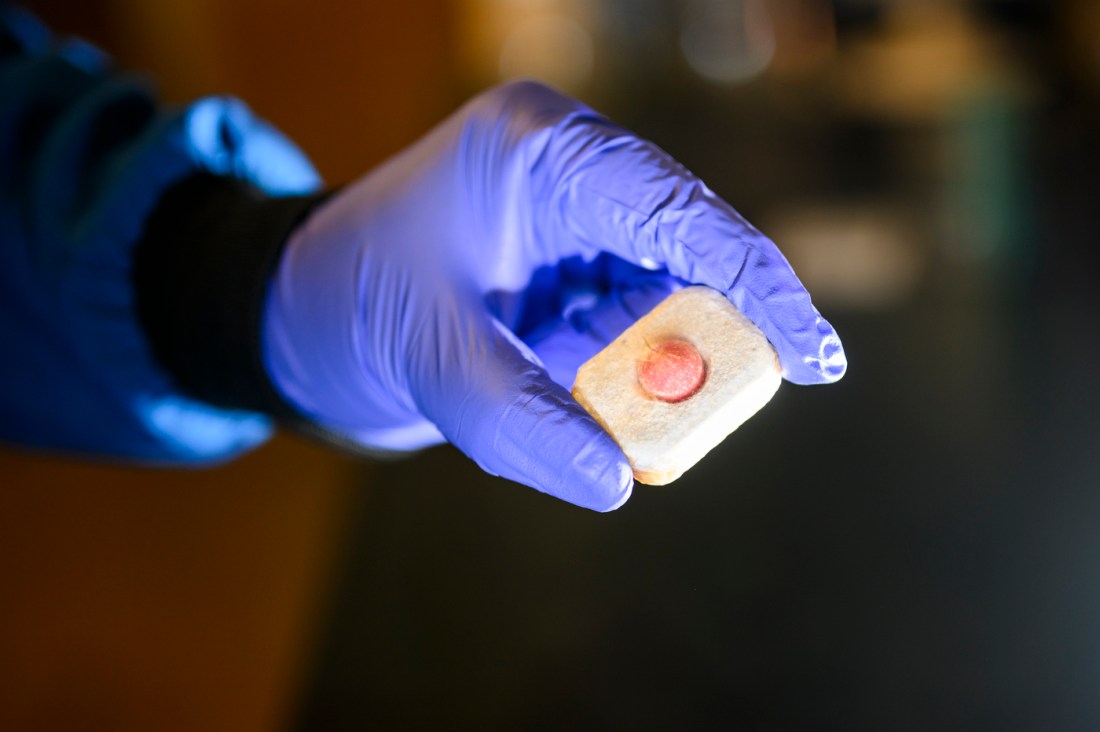

Manjula-Basavanna and Joshi envision that the product could be used for what they call “primary packaging” — that filmy plastic that protects the screen and case of your iPhone, for instance. Detergent pods for dishwashers or washing machines are another potential use. Even proteins embedded in the fibers could provide fertilizer as it breaks down if MECHS were used as a pot for plants.

“Plastic pollution being a global problem, we are focusing on targeting the low-hanging fruit of plastic packaging, which comprises nearly one-third of the plastic market,” Manjula-Basavanna says.

He notes that the typical lifespan of this packaging could be a few days to two years.

“For such a short lifespan of packaging, the petrochemical plastics that can take hundreds of years to biodegrade are unnecessary in many cases and thus a sustainable alternative like MECHS due to its biodegradability, flushability, and mechanical tunability could be a game changer,” Manjula-Basavanna says.