Anne Boleyn’s forgotten years in France: New book explores how politics may have sealed her fate

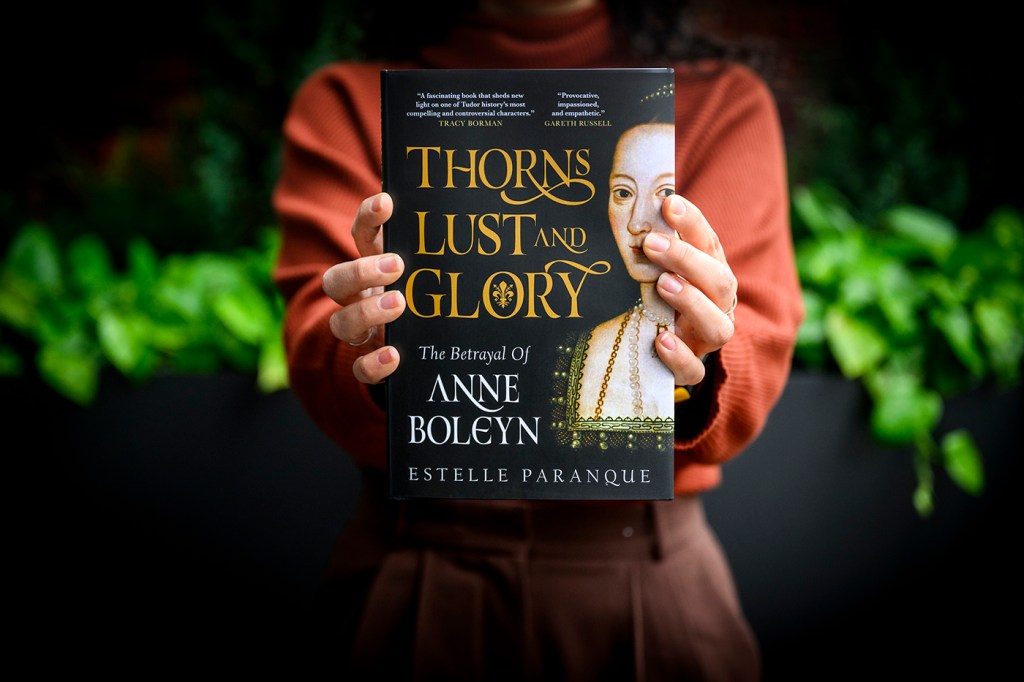

Relations between England and France may have led to Anne Boleyn’s downfall argues Estelle Paranque in her new book, “Thorns, Lust, and Glory: The Betrayal of Anne Boleyn.”

People often remember the wives of Henry VIII by the mnemonic device that spells out their fates: “divorced, beheaded, died, divorced, beheaded, survived.”

In her new book, “Thorns, Lust, and Glory: The Betrayal of Anne Boleyn,” Estelle Paranque, an associate professor of early modern history at Northeastern University in London, is trying to expand the story of Anne Boleyn, Henry’s second wife, beyond just her tragic ending.

The book, which comes out in the United States on Nov. 12, looks into Boleyn’s early years in the French court as a lady-in-waiting to Queen Claude of France and how England’s political relations with France may have contributed to her eventual downfall.

Given that much of Boleyn’s correspondence was destroyed, writing a narrative that restored humanity to the executed queen was a challenge. Paranque, who is from France herself, spoke with Northeastern Global News about how she worked around this to break down the preconceived notions many have about Boleyn and tell a story about a woman caught in the political crosshairs of two nations.

Her answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.

How did you come up with the idea for this book?

I’ve always had an interest in France and the relationships between England and France. I knew Anne Boleyn had spent some time in France, but what can that tell us about her?

I realized that it was very significant in Anne Boleyn’s story, not just the fact that she spent seven years in France, but also her relationships in France and the fact that she was a massive Francophile. She spent seven years in France. She served Queen Claude of France. She really favored the French.

I wondered, ‘What was her relation to them and why didn’t they help her in the end?’ Did they betray her? That’s why it’s called ‘Thorns, Lust, and Glory: The Betrayal of Anne Boleyn.’ But it’s more with a question mark than an assertive claim.

Featured Posts

What was the research process like? How did you evaluate your sources, given many of the accounts of the time were written by ambassadors for the French and Spanish who were biased on the issue of Henry VIII divorcing his wife (Spanish Princess Catherine of Aragon) for Anne?

There’s bias everywhere. There’s always an opinion.

I used some of (Spanish Ambassador Eustace Chapuys’) letters. I did not disregard what he was saying because he has his opinion, but what he was saying was not untrue.

Second, I used French sources so I can really balance what was happening. I looked at what others were saying of the same event.

When you look at the French ambassadors, what’s very interesting is that not everyone really liked Anne. It’s very clear the message from France was that you have to support her, because they really believed that Anne would have a huge influence on Henry and that there would be very strong Anglo-French relations. So here you find very neutral portrayals of her and some of them are positive.

It’s very interesting to counterbalance this with Eustace Chapuys’ letters that are so colorful, so important because they give you so many important details of Henry’s court.

There has already been so much written about Anne Boleyn. How did you find a new facet of her life to explore?

By really looking at the French sources — Anne’s time in France has been covered before. It’s never been covered in-depth.

I tried to bring the French court back to life because if you understand Anne Boleyn’s experience at the French court, you understand the type of woman she’s going to become later on. If you put more of a focus on the Anglo-French relations at the time when she’s courted by Henry and when she became queen, that’s another story. It’s not entirely 100 percent original. It’s a new way of seeing her and understanding her story.

This book hopefully also gives her justice and pushes her back to the center of the story, even though we still don’t have her words. Because that’s the other problem. We don’t have her words.

Exactly, a lot of Anne Boleyn’s correspondence was destroyed after her execution. How did you write around this, given the lack of material we have from her?

That’s where you allow yourself to have more speculation. I made it clear in my author’s note that I do speculate more in this book than I have before because of that.

But (the speculation) is always based on a primary source, and it comes from common sense of how someone would feel or what they could think in that situation. Someone else might have another opinion, but I think it’s the beauty of being a historian and writing about the past. There are records of what she might have said, what she said and then it gives you her voice, even if it’s indirect. It’s what we have to work with.

We can’t just dismiss Anne just because Henry VIII was a horrible man and decided to burn all her letters and try to destroy the legacy she could have had. We know enough where we have to try to guess.

You’ve written several academic books. Do you think writing for the general public is different?

For me, it’s trying to show that history is not boring. History is very important and … not dry. That’s what I’m trying to do and this is the best way to do it.

I want people to understand that they’re human beings who used to live. So, when I write about Anne Boleyn, I don’t just write about a name with dates. It’s about the story of this woman who was wronged on so many levels.

My British editor was emotional when she read the end of (my book) because I try to make the reader walk with me. I want everything I write to be something visual, as if we could have a glimpse into the past.

You can’t do that with academic writing. Though I am making academic points that Anne Boleyn’s story is more complex, that the French played a bigger role in her story, it is not like an academic book with just argument after argument. It’s about her life.