At Northeastern, Israeli artists bring messages of hope between Jewish and Palestinian peoples through music

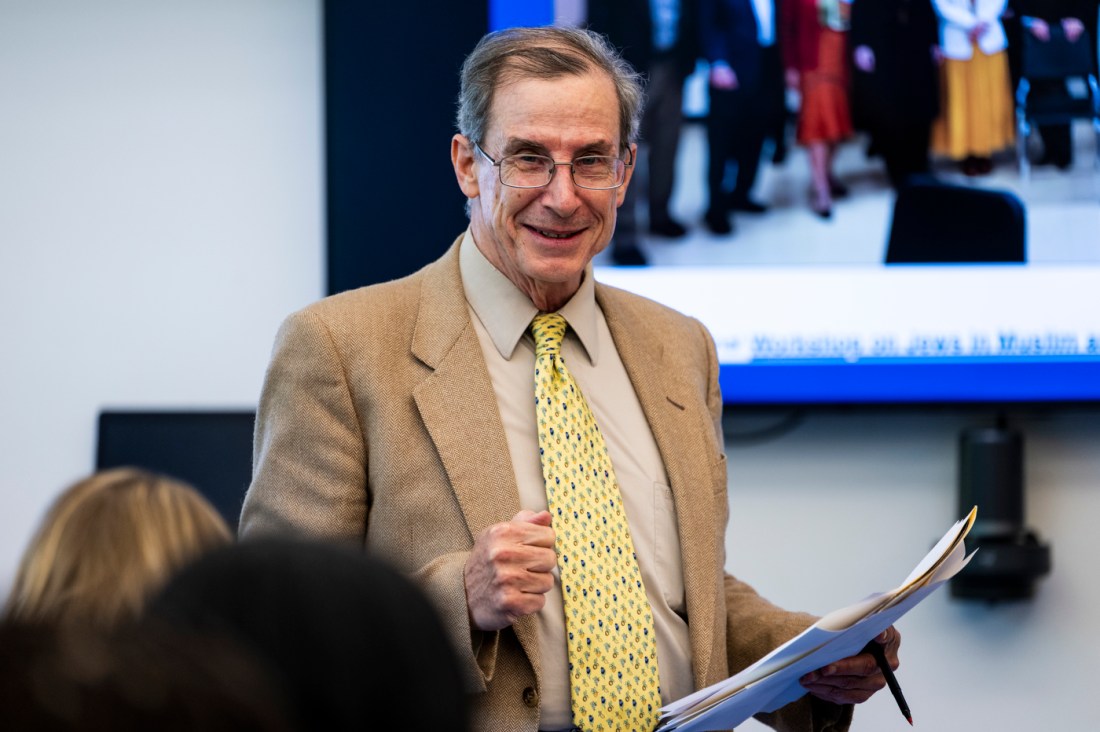

“I wanted to give students the opportunity to think about this other mode of peacemaking, which is through the arts,” says William Miles, a political science professor.

As Israeli musician Neta Weiner hits the first note and stretches the bellows of his accordion, low, rich, emotive sounds of Middle Eastern music start floating through a Northeastern University classroom.

Weiner, 37, starts singing, “So you bought me a little green tree made of plastic…” His wife, Stav Marin, 39, an award-winning choreographer, dancer and singer, joins in, “You were so sure things are falling apart.”

“And you bought me a dagger, painfully sharp,” Weiner picks up. “Because you were certain that flowers I hate,” Marin completes.

They wrote this gruesome love song called “I Wrote You This Song” before Hamas militants launched an attack on Israel from Gaza on Oct. 7, 2023. Since then, the lyrics have taken on layers of new connotations.

Weiner finishes the song with a rhythmic monologue that few people in the room can probably understand because he switches between Hebrew, Yiddish, Arabic and English, sometimes in one sentence or every couple of sentences.

“Yanni,” Weiner says in conclusion, a Hebrew word for “God is gracious” that could also be an Arabic filler phrase for “you know.”

Weiner’s nervous laugh fills a silent pause followed by applause — the audience perhaps is astonished by a unique performing style that Weiner, a poet, musician, actor and director, developed with his bandmates from the Jaffa-based multilingual Jewish-Palestinian hip-hop project System Ali.

The couple visited Northeastern University recently with a lecture-performance, sponsored by the department of political science and the Jewish Studies Program and the music department. William Miles, a political science professor who invited them, explained that while “Palestinian-Israeli reconciliation” might seem utopian, art can convey powerful peace messages in ways people often overlook.

“I wanted to give students the opportunity to think about this other mode of peacemaking, which is through the arts, and have an example of what they are doing in the Middle East itself,” he says.

The session included students from his course on music and politics, and professor Francesca Inglese’s Global Music Cultures class.

Elizabeth Hamilton, a fourth-year student, said she initially doubted the connection between music, dance and politics, but found the discussion persuasive.

“I didn’t even consider how powerful language was as something that moves people and that influences their opinions,” she said, sharing that she might now try to learn a foreign language or two herself.

It was especially powerful to join in on the artists’ version of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” said Luca Williams, a political science and economics major. He was also moved by various stories the couple shared.

Marin’s work explores the physical-verbal connection through movement, dance and speech. She presented an excerpt from her solo performance, inspired by her emotional and bodily reactions to televised speeches of Israel’s defense minister.

Together, Marin and Weiner also perform as a duet, drawing from pop culture, Quentin Tarantino, Eminem, the Bible and Kabbalah. Their award-winning show, “Cut. Loose,” questions dominant narratives on power, gender, militarism and politics.

Weiner’s and Marin’s world view was strongly influenced by living in Jaffa, a 4,000-year-old port city near Tel-Aviv. Jaffa has been a center of cultural exchange since ancient times. As one of a few “mixed cities” in Israel, Weiner says, Jaffa is a home to Palestinians, Jewish Israelis and immigrants who share the same apartment buildings and bomb shelters.

“Jaffa brought many questions to my life,” Weiner says. “Questions regarding ownership and identity, and language and power dynamics.”

Weiner, born in a kibbutz, grew up isolated from other communities. When he first met Palestinian rappers in Jaffa, he collaborated with them without knowing their language. Unlike Palestinians in Israel who have to learn Hebrew, he says, Jewish Israelis typically don’t learn Arabic.

Editor’s Picks

“When people are scared of Arabic, the best cure for it would be [to] learn it, then you stop being scared of it,” Weiner says. “One thing that happens when you learn a language is that you stop hearing it — you start hearing people.”

He and Marin have been learning Arabic and Yiddish, reconnecting with their roots in the Jewish diaspora.

Weiner co-founded System Ali (slang for “pump it up”) with his Jewish and Palestinian friends in 2007. System Ali, which includes male and female members singing in Hebrew, Arabic, Russian, Yiddish, Amharic and English, Weiner says, rapidly developed into an artist collective and a cultural movement.

The project, rooted in hip-hop, draws from many genres of music from classical and popular Arab music to jazz, Jewish medieval folk music and Russian songs and aims to connect people across languages and cultures.

“We’re artists, so our art, in a way, is our attempt to suggest a different reality, to suggest a different home, obviously based on equality and justice,” Weiner says.

The devastating events of Oct. 7, 2023, Marin and Weiner say, affected their closest friends, both Jewish and Palestinian, who lost loved ones in the attacks and subsequent warfare.

Since then Marin and Weiner and their friends have been on an “emergency tour,” promoting messages of hope and reconciliation through their music and art.