A Northeastern dean wore an AI-knitted shawl to her Academy of Arts and Sciences induction. Here’s the story behind its creation

Khoury College of Computer Sciences dean Elizabeth Mynatt turned to Megan Hofmann’s lab for a garment embroidered with symbolism from her career in AI and assistive technologies.

Elizabeth Mynatt had a big event coming up, and she needed something to wear. But instead of Nordstrom’s or Club Monaco, the dean of Northeastern University’s Khoury College of Computer Sciences turned to a small machine lab nestled on the ground floor of the EXP research complex on the Boston campus.

In late September, Mynatt was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences — an acknowledgement of her groundbreaking contributions as a researcher at the intersection of artificial intelligence and assistive technologies. For the Sept. 21 ceremony in Cambridge, Massachusetts, she wore a custom shawl designed and manufactured in assistant professor Megan Hofmann’s lab — not at a traditional sewing machine, but with artificial intelligence.

“When this happened, Megan immediately sprung to mind,” Mynatt says. “I could be at this amazing ceremony, but have something that carries Northeastern with me and allows me to talk up her amazing research.”

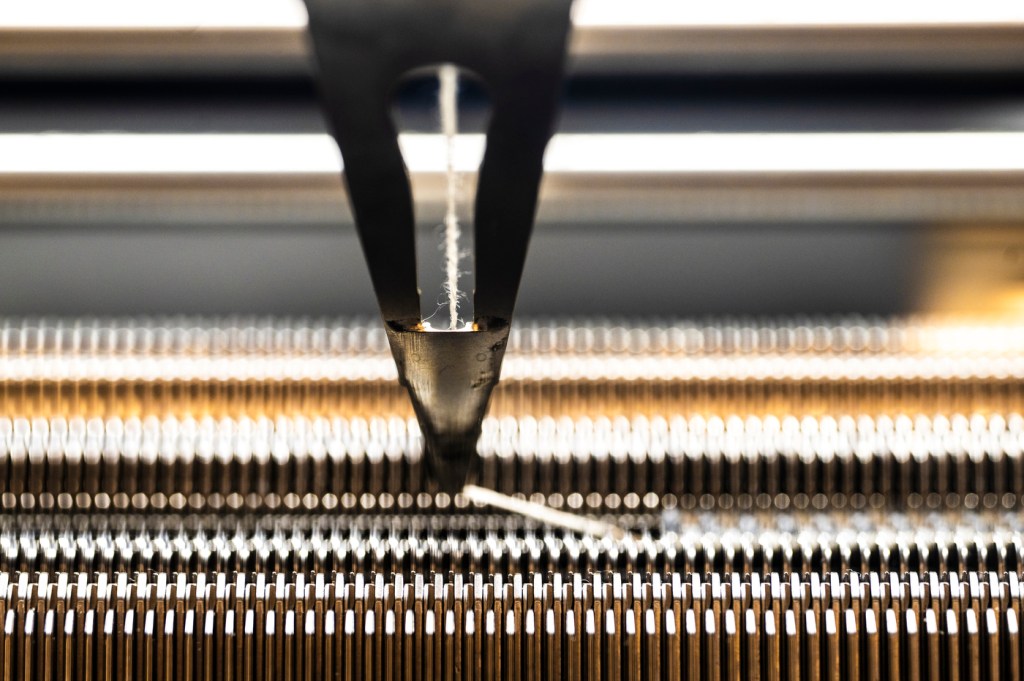

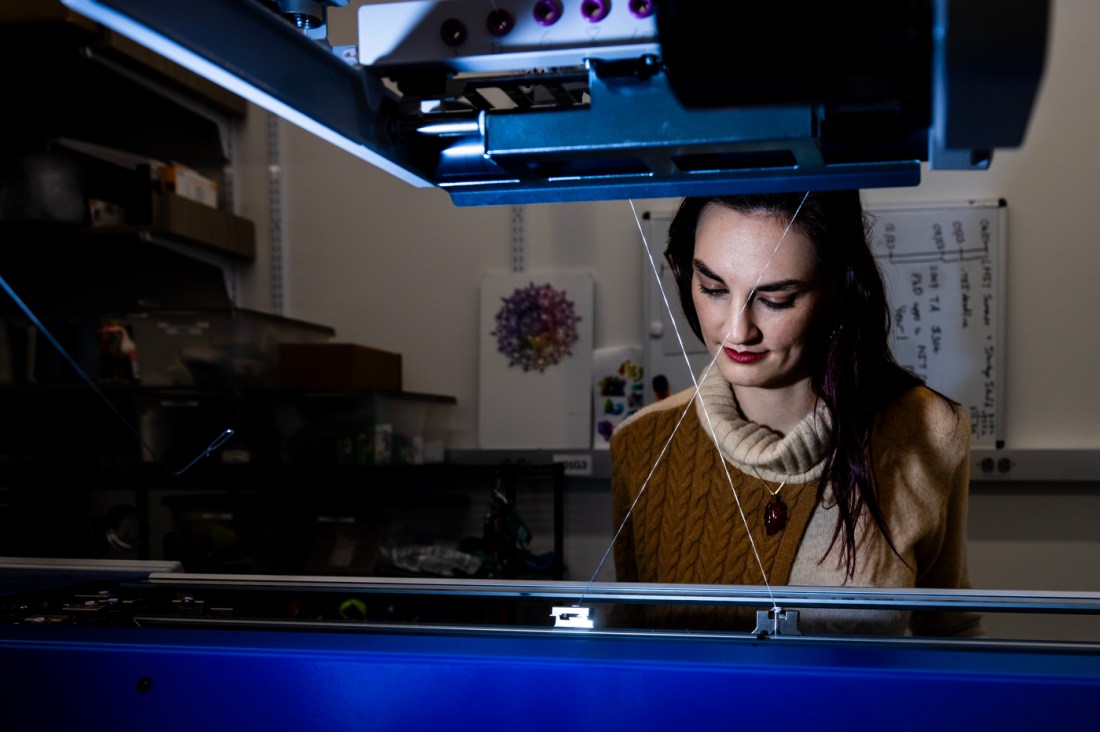

Hofmann’s work focuses on developing programs for textile manufacturing, with broader goals of making their production more adaptive and sustainable. Mynatt recruited her to Northeastern in 2022; last year, her lab released KnitScript, an open-source programming language for industrial-scale machine knitting.

“Aside from the knitting work, a lot of my lab is focused on technology for people with disabilities,” Hofmann says. “And Dean Mynatt, in addition to her other accomplishments, is a matriarch of that field. She’s been in it for a long time.”

When Mynatt learned of her academy induction this past spring, the two women began brainstorming on how to reflect that body of work in a knitted piece. The design process was wide open: The only specifications Mynatt gave were that the dress code was formal, and she’d probably be wearing navy. For the rest, Hofmann turned to an unlikely source of design inspiration: Mynatt’s academic CV.

“One of the things I get really excited about with the systems I’m building is the ability to incorporate data and computation into these designs in a way that traditional knit programming doesn’t let you do,” Hofmann says.

A motif emerged. Some of Mynatt’s early research focused on leveraging data to support aging populations in their homes. In 2001, her team designed a prototype of a digital picture frame equipped with butterfly-shaped lights, attached to sensors throughout an elderly person’s home. By growing larger or smaller, dimmer or brighter, the butterflies could indicate data like movement and vital signs — the idea being that the person’s loved ones could keep an eye out without being physically present in their house. The project was covered widely in the national press, including the New York Times.

So in the shawl, butterflies became emblematic of the major milestones in Mynatt’s career. Embroidered into the light blue and white PUMA stretch yarn, they’re plotted in a looping, loose-lined pattern that looks random but is in fact the rigid, programmatic rendering of key data points from Mynatt’s academic body of work.

“The timeline was really interesting to me — being able to generate the butterflies to be spaced out that way,” Hofmann says. “It’s a really simple example of that kind of work.”

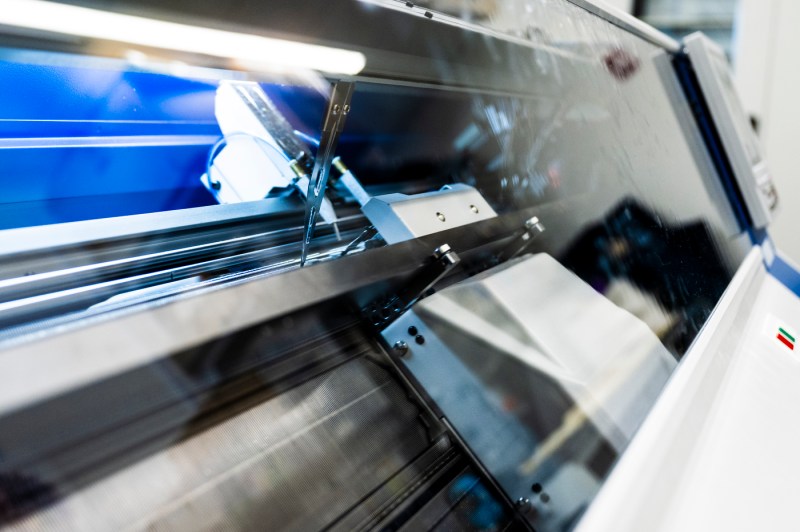

The programmed shawl measures about 5 feet long and a foot wide; it can be made from start to finish on an industrial knitting machine in approximately half an hour. About the size of a large office desk, such machines are in wide use in commercial manufacturing around the world. Hofmann’s research is focused on designing universally accessible programs — similar to those used in 3D printing — to make textile makers’ products more responsive and sustainable.

“You have a common language that people can develop across machines, and then you build design tools on top of that base language,” Hofmann says.

“We’re interested in supporting things like whole garment knitting, where you’re essentially knitting without waste — you’re not cutting and sewing and throwing away material, you’re knitting with a single yarn. This ends up as a much more sustainable [process], and we’re able to focus on things like ‘just in time’ manufacturing and custom sizes, making sure that clothing fits to our bodies the way we want it to.”

For mass market retailers, that could mean less wasted inventory; clothing companies “don’t have to knit thousands of units, most of which [go unsold and] get thrown away.”

Sebastian Law, an undergraduate researcher from Seattle University who joined the lab through a partnership with the University of Washington’s Access Computing program, was one of the first people trained on the KnitScript programming language; he used it to write the code for Mynatt’s shawl.

“I learned a lot about clothing design and different colorwork techniques that can be used on the knitting machine,” he says. I also learned how to get a colorwork design on paper to knit correctly and how to write a large coding program to create a piece of clothing, which was a great experience.”

Now, as a graduate student in Seattle, Law is collaborating with Hofmann on a system to enable easily customizable clothing features for people with disabilities. “The training I got through this project and over the past two summers from Dr. Hofmann has been extremely helpful,” he says.

Featured Posts

Law’s handling of the project is a testament to how much Hofmann’s systems have developed in a short amount of time.

“The way I had been doing it when I started in this field, that shawl would have taken me years to figure out,” she says. “To have an undergraduate researcher be able to do that, not even as the primary thing they were doing over the summer — just that difference over a few years has been really exciting.”

The lab has a bevy of other projects in the pipeline, many of which continue in the tradition of Mynatt’s work using programming to solve problems of accessibility. One focuses on developing garments that can sense body movements, with the goal of understanding the mechanisms of dance and movement therapy. Another uses large language models to facilitate 3D modeling by blind users. One of the most complicated projects involves knitting garments that change shape in response to outside data: a prototype of one such piece will be used as a costume this year in a production at the Boston Opera House.

For Mynatt, having a piece that embodied those exciting new developments as she looked back on her groundbreaking work gave an already special achievement an almost bottomless sense of meaning.

“It was so special to me, because I’m literally wearing my career,” she says. “And then because it was Megan and her work, it was also extremely, extremely current. I had this sense of 30 years wrapped around me, but with the energy of a relatively new faculty member doing amazing work, whose career I feel responsible for. That made it not just history.”