New research sheds light on how the 2016 and 2020 elections were won, lost — and the ‘critical’ role disinformation played

Koen Pauwels, distinguished professor of marketing at Northeastern, offers insights into how disinformation, social media engagement and news coverage influenced political support for the major party candidates.

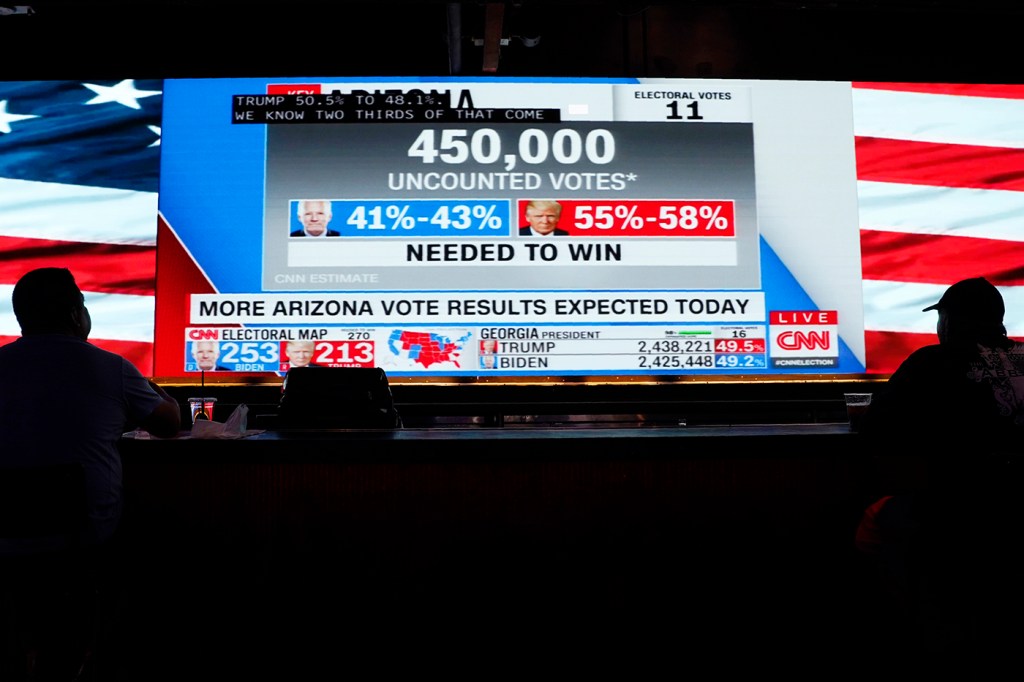

Elections today can generate a lot of noise. The rise of digital media means that, in addition to 24-hour cable news, social media features prominently in campaigns and elections.

Using the latest in machine learning modeling, Northeastern researchers sought to cut through all that noise — specifically, as it pertains to the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections. In new research published in the Journal of Business Research this week, they showcase how effects such as disinformation, social media engagement and news coverage influenced political support for the major party candidates.

“We set out to have the most comprehensive analysis of all the drivers of political support,” says Koen Pauwels, distinguished professor of marketing at Northeastern.

What Pauwels and his colleagues found, through analyzing changes in polling data — setting aside the candidates’ own marketing efforts — both online and offline, word-of-mouth chatter “significantly influences candidate actions, media narratives and voter behavior.”

Offline word-of-mouth conversations, in particular, in both 2016 and 2020 had a “pretty big effect” in bolstering former President Donald Trump compared to former Secretary of State Hilary Clinton and President Joe Biden, respectively. Offline conversations are those that do not occur on public-facing platforms but instead in bars, at campaign rallies or other public spaces.

The researchers also found that disinformation played a central role in shaping both discourse and polling during the two election cycles.

“The key finding of this research is that the topic of disinformation really matters, but it depends on the topic,” Pauwels says. “In both 2016 and 2020, we found that some topics of disinformation were really inconsequential, or even backfired against the site that was spreading it, and others were really effective — and furthermore, you could see those effects in certain polls but not in others.”

Researchers scraped data from platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and X (formerly Twitter) to measure changes in political support across 2016 and 2020. They tracked data points such as the daily number of followers on official accounts; user reaction to the candidates’ posts; the volume of disinformation associated with, or targeting, the candidates; the candidates’ various television ads as well as news coverage of them.

Featured Posts

For perspective, in 2016 the researchers were able to analyze over 80 million tweets, with some 10 million mentioning just Clinton, 17 million mentioning just Trump and the remainder mentioning both); 4.5 million and 2.5 million user comments from Trump’s and Clinton’s Facebook pages, respectively; and 2.7 million and 2.2 million user comments from their Instagram accounts, respectively. (The researchers would go on to parse nearly 133 million tweets as part of their review of the 2020 election.)

Such a sweeping analysis — made possible only by machine learning modeling, Pauwels notes — provides some clear insights about the role certain media played in both election outcomes, but it also helped researchers better understand the minutiae.

For instance, researchers found that when Clinton discussed women’s issues, such as reproductive rights, on Instagram during the 2016 election, she saw an increase in support — but lost support when she did so on Twitter. Researchers also found that the disinformation surrounding Clinton’s private email system controversy was “highly effective” in driving the probabilistic polls that were ultimately correct in forecasting the election, but not so when it came to the traditional polls.

The researchers also found that other developments beyond the candidates’ control, such as leaks, can spur disinformation on topics not immediately tied to those developments.

For example, disinformation about Clinton’s relationship with Muslim Americans — a source of much controversy during the 2016 cycle — increased following the publication of a New York Times article detailing the FBI’s finding that there was no Russian interference in the election, but decreased following Wikileaks cables about her campaign chair John Podesta. “Thus, both leaks and traditional news articles trigger increases in disinformation volume,” the researchers wrote.

“Additionally, we find that the relationship between disinformation and media coverage is the only unidirectional effect, with disinformation driving media coverage, but not the reverse,” the researchers wrote.

The feedback loop between social media and traditional media is subtle, but mostly understood: “There is this strong interaction between social media and mainstream media, in the sense that they basically are all gatekeepers of information, and they pick up on each other,” Pauwels says.

But Pauwels says he thinks the impact of social media on elections has started to eclipse the traditional media.

Pauwels says the results offer campaign managers a fresh playbook. For one, he says campaigns should diversify their sources of information, get a better handle on how voters feel about the economy and focus on devising strategies to limit the fallout caused by disinformation.

“I think we’re one of the only studies in marketing or political science that also has offline word-of-mouth conversations,” Pauwels says. “Very often online chatter is seen as a bubble, specifically if you only look at X or Facebook. And what you see there is just not representative of how the majority of Americans feel or behave.”