Northeastern researcher uses engineered bacteria that fights cancer by shrinking tumors, showing potential for new treatments

“What we did is basically use bacteria to activate the immune system, and the immune system kills the tumor,” researcher Shaobo Yang says.

He admits it sounds a little bit scary.

But a Northeastern University researcher says a new method using live bacteria to shrink tumors in mice has proven safe and effective in a recent study.

“Generally, what we are trying to do is we use bacteria to cure cancer,” says Shaobo Yang, a Ph.D. student at Northeastern’s College of Engineering. “It sounds a little bit dangerous, but a lot of bacteria are nonpathogenic, meaning they don’t secrete toxins.”

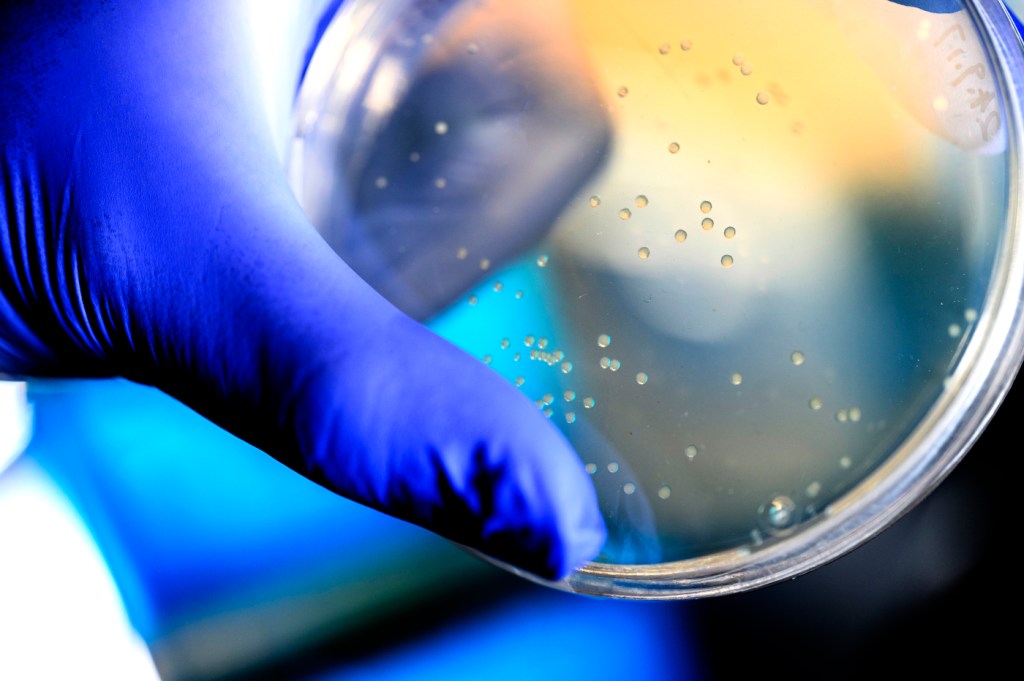

In the study, published by Nature Biotechnology, Yang and collaborators affiliated with the University of Michigan and the Dana Farber Cancer Institute, used nonpathogenic E. coli specifically engineered with proteins on its surface to elicit an immune response and attack and kill cancer cells.

The bacteria are “tumor-homing,” as Yang describes it, naturally seeking out tumors.

The proteins, meanwhile, signal the immune system to attack and kill the cancer cells by activating T-cells and NK cells.

The researchers tested the delivery method by injecting the engineered bacteria into mice with melanoma and colorectal cancer.

The study found that 50% of the mice with colon cancer were cured by the optimized bacteria.

Combining the optimized bacteria with state-of-the-art immunotherapy, meanwhile, resulted in a 90% cure rate for mice with colon cancer.

Thirty percent of the mice with melanoma — a more difficult cancer to treat — were cured, according to the study.

“What we did is basically use bacteria to activate the immune system, and the immune system kills the tumor,” Yang explains.

Moreover, when the cured mice were given another tumor, their immune system went into action and attacked. Yang says this means that the immune system “learned” to remember the cancer cells, making it harder for the cancer to return.

The study also suggests it is not just mice that can benefit.

To test whether the method would potentially work on humans, researchers injected the optimized bacteria and NK cells into immunocompromised mice with human, hard-to-treat mesothelioma tumors.

“The bacteria with the NK cells significantly suppressed tumor growth in the immunocompromised mice,” Yang says. “This increases the chance that it could be translated into a human clinical trial.”

The study also showed that this method was safe.

Because the bacteria is “tumor-homing,” the study found that it accumulated roughly 1,000 times more in the tumor than in other organs like the spleen, liver or kidney — places where the bacteria could potentially cause inflammation or sepsis.

The researchers next want to move toward a clinical trial to see if the method could cure human patients.

“We’re looking forward to the future achievements of this platform, and we really hope that we can help patients to push forward a tumor-free world,” Yang says.