Can you measure pain objectively, based on science? Northeastern researcher uses AI to develop ‘pain-o-meter’

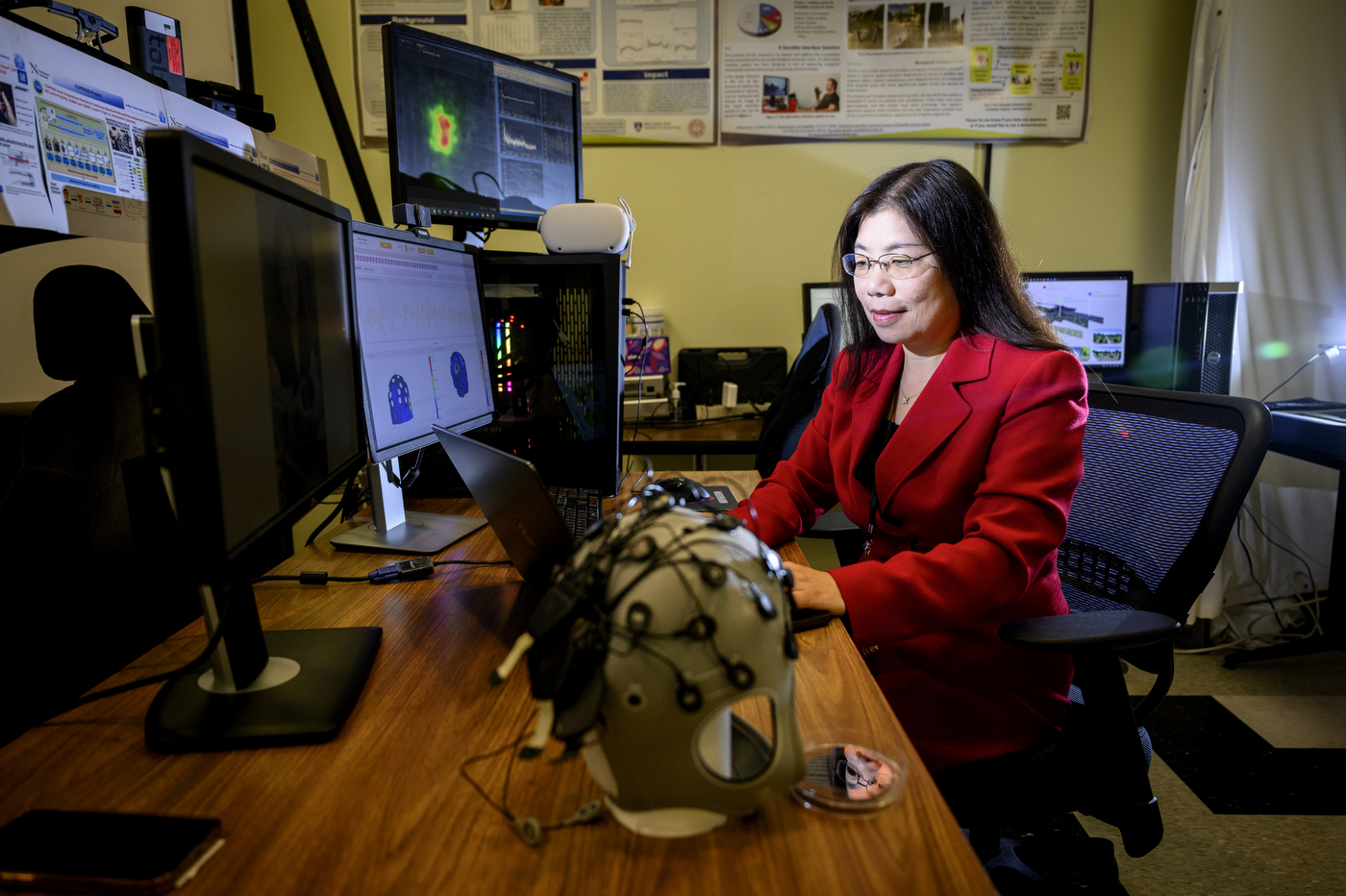

Yingzi Lin, a professor of mechanical and industrial engineering, uses AI and machine learning to pin down the subjective experience of pain.

When Northeastern professor Yingzi Lin visited her father after his hip replacement, doctors asked him to measure his level of pain on the standard score of zero to 10.

He couldn’t do it, says Lin, who accompanied her father to his appointments.

Maybe it was his cultural background from being raised in China or the fact he had lived with chronic pain for a long time. But the number system didn’t work for her father, nor did it work for Lin when she was delivering her first child at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“I had an induced delivery but when the nurse would come to check on me, I would always tell them, ‘I’m OK,’” Lin says, even when her pain was nearly off the charts.

“I hated to give very high numbers and say, ‘I’m a nine or a 10’ because I was worried that I might get some unnecessary treatment from the doctors.”

Lin, who is a professor of mechanical and industrial engineering, says the experiences gave her the idea to use her engineering skills to pin down the subjective experience of pain.

“How can you measure it objectively?” she says.

A bucket of ice water

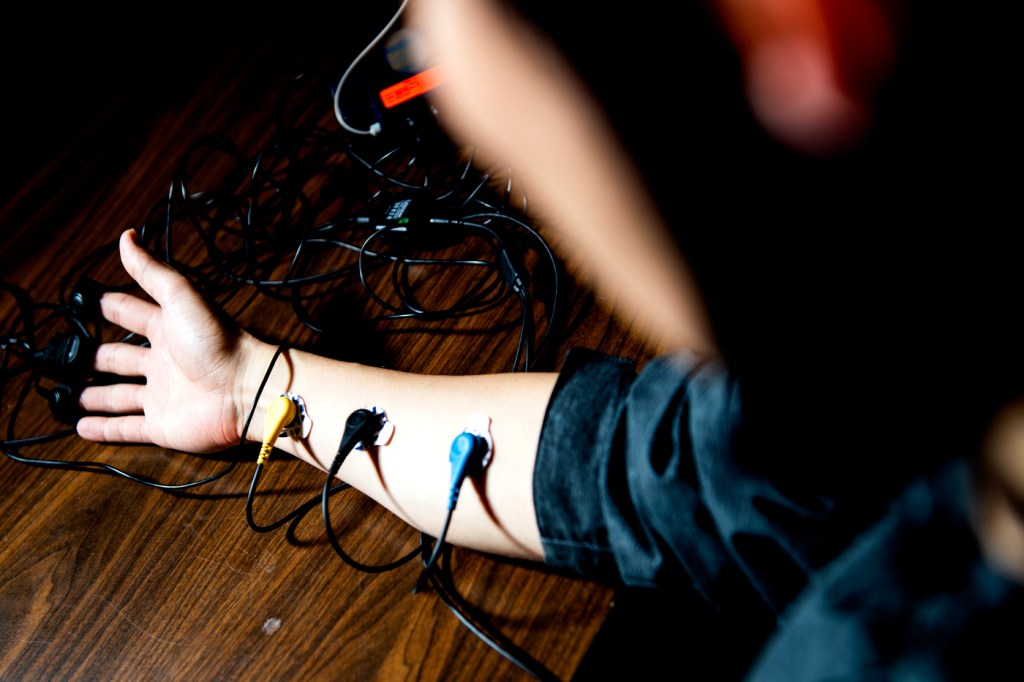

For her research, Lin uses pin pricks, applied, steady pressure and a test that calls for participants to dunk their hand in a bucket of ice cold water that is maintained at around 32 degrees Fahrenheit.

“They are free to stop any time, as needed,” says Lin, who was the first test subject.

While running the tests, she uses sensors placed on participants’ heads and chests to collect a bundle of physiological responses, including, heart rate, respiration, muscle movement, galvanic skin response and brain wave signals.

Facial expressions also factor in, as do eye movements and dilation, says Lin, whose research was recently featured in a Nature article about how a “pain-o-meter” could improve treatment.

Featured Posts

The responses are fed into machine learning algorithms to find patterns and relationships that will be a sure-fire indicator of pain levels.

AI models are used to develop what is known as information fusion from the multiple signals being collected, Lin says.

Participants’ own reports of pain are also taken into account, Lin says. “By doing so we are comparing the physiological responses, objective reports, in real time with AI assistance.”

“After collecting all those signals, we are trying different combinations because in practice it might not be feasible to have all those measurements in a clinical setting,” she says.

For instance, the information from brain waves provides scientifically useful information about pain levels, but it might not be possible to have EEGs in every labor and delivery room or emergency department bay.

What Lin and her team, which includes a hospital patient safety director, are looking for is a bellwether that mirrors information collected from brain waves and other signals.

“We are working on what are the best indicators, the most physically feasible combinations that can be useful,” she says.

“Pain touches everybody’s life,” whether it is acute or chronic, Lin says.

Lack of objective measurements can result in under treatment for babies, people with limited communication skills and people who are unconscious following surgery, which in itself can cause trauma.

On the flip side, pain management physicians have told Lin that they suspect patients sometimes report a very high pain score so that they can get medication they don’t actually need, which could lead to opioid dependence.

When it comes to patients and pain, “We need to have a deep understanding of what they are experiencing,” Lin says.

She says she expects to develop commercial applications of her research, which has been funded by the National Science Foundation, in the next few years.

“Moving forward, my ultimate goal is to not only use this in a clinical setting but maybe a home device that can be useful, especially for patients with chronic pain,” Lin says.