Rupert Murdoch’s Wapping dispute shaped media in the UK. New research looks at what happened on the frontline

Lecturers Sam Kemp and Amil Mohanan researched Murdoch’s 1980s battle with the printing unions by interviewing those who picketed and digging through newspapers run by those striking.

LONDON — Media tycoon Rupert Murdoch’s bitter yearlong standoff against the printing unions in 1986 had everything: deceit, mass sackings, government clampdowns and clandestine operations.

And it all happened only a few hundred meters from Northeastern University’s London campus. What occurred during the bloody and fraught feud, in what has become known as the “Wapping dispute,” irrevocably changed British industrial relations and its newspaper sector.

The dispute is also the subject of new research by Northeastern professors Sam Kemp, an assistant professor of creative writing, and Amil Mohanan, an assistant professor of data and artificial intelligence. Their research includes interviews with trade unionists involved and an examination of articles in newspapers run by the unions and strikers, with the pair making digital reproductions for future preservation.

According to Kemp, the Wapping dispute “really proved that you could not strike anymore in the same way that you could” in the past and marked a new dawn for the U.K.’s newspaper industry.

“It was a huge victory for the media and for managers and organizations,” he says. “It was a failed strike; there was no victory. All the big Fleet Street papers moved out to east London and other areas like that almost overnight. It proved to everyone that Murdoch could win and could do this, and so it instantly killed off the culture in Fleet Street.”

The context for the strike lies in the industrial unrest of the 1970s and ’80s in Britain.

Before Murdoch had added The Times and The Sunday Times to his British media stable in 1981, the former owners of the broadsheet newspapers in 1978-79 had endured year-long industrial action with unions that cost the firm nearly £40 million ($53m), says Kemp. That tussle had brought home to Murdoch the power that the heavily unionized print workforce could wield.

Fed up with a perceived trade union stranglehold over the U.K. printing press, the Australian-born businessman covertly set up a new headquarters in Wapping, east London, using secretly imported computer technology from the U.S. that was designed to make the process of producing newspapers quicker and cheaper.

The owner of the News International group falsely told union officials the site would be used to produce a new newspaper, The London Post. However, his plan was to instead relocate his entire roster of British newspapers — The Sun, The Times, The Sunday Times and The News Of The World — away from its traditional Fleet Street home, with its aging printing presses, to his new base in the docklands.

After years of drawn-out negotiations between unions and News International (now known as News UK) over tough new contract terms — officials dubbed the company’s proposals “The Serf’s Charter” due to its inclusion of a no-strike clause and demand for the end of unionization — trade union chiefs ordered workers out on strike.

On Jan. 24, 1986, almost 6,000 print staff downed tools and were effectively sacked. That same night, Murdoch’s Wapping operation kicked into gear with barely a hiccup.

Kemp says Murdoch’s carefully guarded plan meant he was able to fire up new modern presses using a brand new workforce and his usual band of journalists without ever missing a day of printing.

“Murdoch, the newspapers, the company — they were absolutely prepared,” the academic says.

“The newspaper came out as normal, printed here [in Wapping] — no disruption whatsoever. It is incredible,” he says. “You’ve got 5,500 print workers out on strike overnight but yet the next day, the company resumed its business with virtually zero disruption.”

The ploy would spark one of the biggest industrial disputes in British history and became a major test for the anti-union laws introduced by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party government in the 1980s, brought in during a long-running battle with striking coal miners.

Workers who had been sacked by News International spent just over a year picketing and attempting to disrupt the operation at what became known as “Fortress Wapping.”

News International collaborated with the electricians’ union — the Electrical, Electronic, Telecommunication and Plumbing Trade Union — behind the printing unions’ backs, with leader Eric Hammond agreeing that his workers would operate the new plant, Kemp explains.

The Wapping workers were transported on buses to operate the printing presses in the 15-acre fortress. Kemp and Mohanan found one route published in a strike newspaper showing that workers were taken past Devon House, now home to Northeastern’s operation in the city.

Murdoch and his team had built Wapping knowing it would have to withstand a battle with their now ex-workers.

Linda Melvern, in her book “The End Of The Street,” reported that News International’s printing plant was “ringed with razor wire in huge coils, fenced with steel” and surrounded by CCTV. The historic walls of St Katherine’s Dock — the area home to Northeastern’s main teaching block — acted as a natural protective barrier.

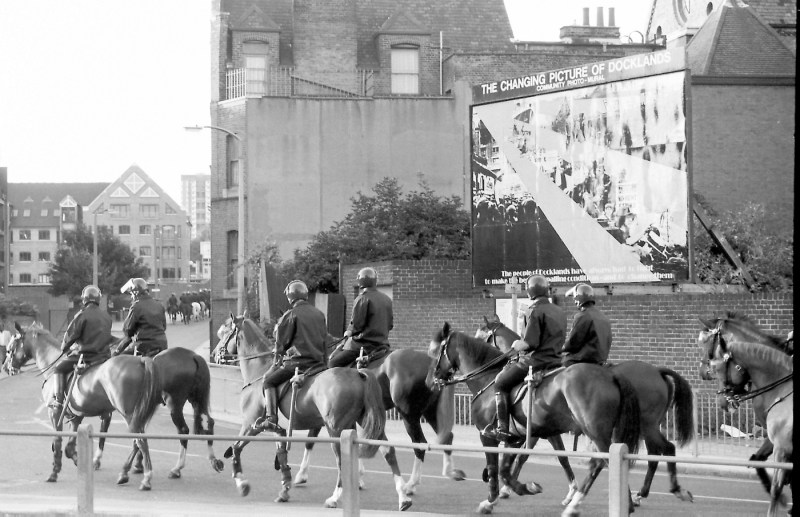

On top of that, police on horseback patrolled the perimeter to ensure the roads were clear for newspaper trucks to start their deliveries, with strikers involved in sometimes bloody skirmishes with officers.

Featured Posts

The context behind the dispute was Thatcher’s new Employment and Trade Union Acts, says Mohanan and Kemp, with the laws making mass industrial protest much harder to organize. Pickets outside a workplace were restricted to just six people and unions in other sectors were banned from striking in solidarity.

“The strike was the union’s greatest asset,” Kemp continues. “It was the most powerful technique — they could get thousands of people coming out on strike, literally physically blocking the roads. Legally, they could no longer do that.”

In the streets around Murdoch’s newly located London empire were battles between police and those wanting to picket. According to a report in The Guardian, on the first anniversary of the dispute, 168 police were injured, along with scores of demonstrators, as up to 1,000 police in riot shields stormed the ranks of 13,000 demonstrators.

Workers kept up the struggle for 13 months but in the end folded as money, energy and public support waned, with the unions negotiating redundancy packages.

Today, little is left of Murdoch’s so-called fortress, with the printing plant sold for £150 million ($200m) in 2012 to be redeveloped into housing and retail space. In its place are new blocks of flats, minimalist coffee shops, edgy restaurants, supermarkets and even a new public space — Gauging Square — with a water feature that children can be seen playing in during warm weather.

Mohanan says the changing shape of the area is what served as inspiration for the joint project, which saw the academics work with the Marx Memorial Library in central London and those on the frontline of the dispute.

“We’re based [near] Wapping so we wanted to do something about the local area and we heard all of these [strike] stories,” Mohanan says. “But there’s nowhere to place all of the events. We went through the strike newspapers and placed all the different events to try and figure out where everything happened.”

The academics have written a chapter about the dispute and the part played by picket line newspapers in a yet-to-be published book. The language used by the workers’ newspapers, the unions and Murdoch’s company also inspired a series of poems penned by Kemp.

“I think [the poems are] a reflection on what occurs in a place but when there are no scars left there,” he says. “You have a real cognitive dissonance when you look at some of the images because when you walk around here, it is so pleasant and lovely.

“But you see the photos and footage with bloodied people being carried off and lines of riot and mounted police behind them. It is really hard to have those two spaces exist in one place, so I think the poetry was a little bit about that tension.”