Should Tua Tagovailoa keep playing after his third concussion? A brain researcher discusses the risks

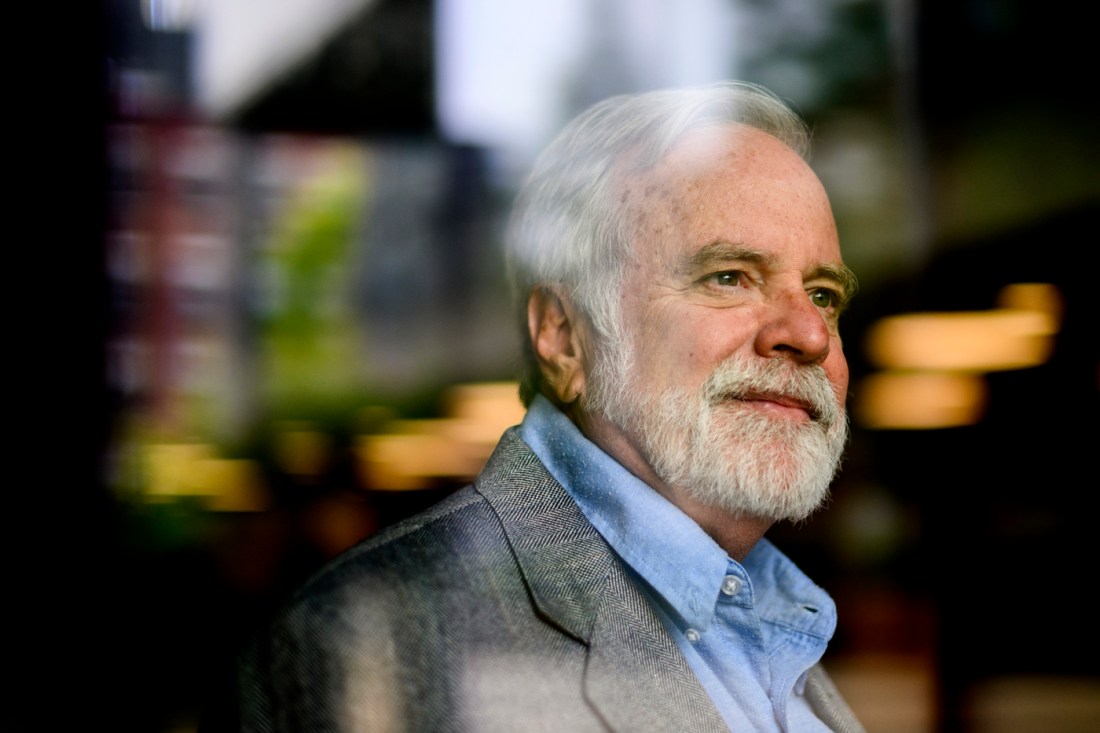

Northeastern’s Art Kramer assesses the issues facing the star NFL quarterback, who on Thursday suffered his third concussion since 2022.

Tua Tagovailoa, the star quarterback of the Miami Dolphins, suffered a concussion Thursday night that may jeopardize his NFL career.

Tagovailoa, 26, ran head-first into Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin and remained on the grass field for two minutes before walking to the sideline. Tagovailoa was ruled out for the remainder of the second half with a concussion.

Tagovailoa has officially been diagnosed with three concussions since 2022. He has acknowledged that he considered retiring from football two seasons ago after being diagnosed with two concussions followed by a blow to the head that resulted in changes to the NFL’s concussion protocol.

Tagovailoa went on to play in every game last season. In July he signed a $212.1 million contract extension.

Should Tagovailoa continue to play football? What are the risks?

Northeastern Global News discussed these issues with Art Kramer, a professor of psychology and director of the Center for Cognitive and Brain Health at Northeastern University.

What are the risks after suffering a concussion?

This is not the kind of injury you want to continue to play through, because if you have additional concussions, it tends to be worse in terms of the long-term recovery.

You certainly have damage when the injury occurs. Can that heal to some degree? It depends on how severe it was and how many you’ve had, but you tend to pay a price.

We did a study a number of years ago where we looked at men who had up to four concussions before the age of 24; then we looked at them when they were in their 40s and 50s, and then again in their 60s and 70s. We examined memory and compared them to comparable folks with comparable education, and we also did structural MRIs of the hippocampus, which is an important area in the brain that subserves a number of aspects of memory.

And what we found is that there was a divergence between the folks who had had the concussions, though it wasn’t quite substantial or significant in their 40s and 50s.

What are the possible consequences as the sufferers grow older?

By the time they were in their 60s and 70s, the effect [of concussions] was beyond noticeable. It was statistically significant, both in terms of the structure of their hippocampus, which we need throughout our life to help us encode new memories, and also for their performance on memory tasks.

Aging in and of itself tends to bestow problems on memory and problems on brain function and structure. And when you multiply that with multiple concussions, the probability of paying a higher price goes up. One of the risk factors for Alzheimer’s and related dementias is head injuries. So you also increase your risk when you’re older in terms of maybe not being able to live independently and other kinds of things that you’d like to do.

Featured Posts

You are a former amateur boxer who has suffered multiple concussions. How would you describe the experience?

The first time it happens, you are very confused, because all of a sudden you can’t remember things like where you live or how to open your locker.

When you have more concussions, you get used to the feeling. I still remember sitting down in front of my locker in the gym after having a concussion — it wasn’t my first one — and thinking, OK, wait 10 or 15 minutes and I’ll probably remember my locker combination, and I’ll remember where I live so I can walk home.

In some ways you become used to these things, and it’s not a good idea that this happens. But I think when you’ve had multiple concussions, I’m sure as it is for this player, he’s experienced these symptoms before. He’s fuzzy. He can’t remember things. Maybe he doesn’t remember what he’s doing as he’s laying on the ground. It depends on how hard he was hit and in what direction.

Should Tagovailoa consider retirement?

I’m sure he is thinking about it. And I’m sure he has access to really good neurologists and folks who specialize in brain trauma. It’s a matter of working with his physicians, the team physicians and other physicians that may examine him to determine how serious it is and how long these episodes last. They tend to do MRIs but you don’t often see damage on the MRIs because the damage tends to be diffuse.

But I wouldn’t tell anybody they shouldn’t play. People have to make these decisions for themselves. And athletes often tend to take higher risks than non-athletes.

For many years, I was not only a boxer but also a high-altitude mountain climber, and I’ve actually done research on risk assessment. The general belief in the newspapers and magazines was, well, these mountain climbers just don’t know what they’re getting into. And what I found was they know exactly what they’re getting into. In fact, they’re better at assessing risks than equivalently educated people, and they are willing to take on those higher risks. I imagine that many professional athletes also understand the risks and the consequences.