Nearly one in four Americans know someone addicted to opioids, Northeastern-led research says

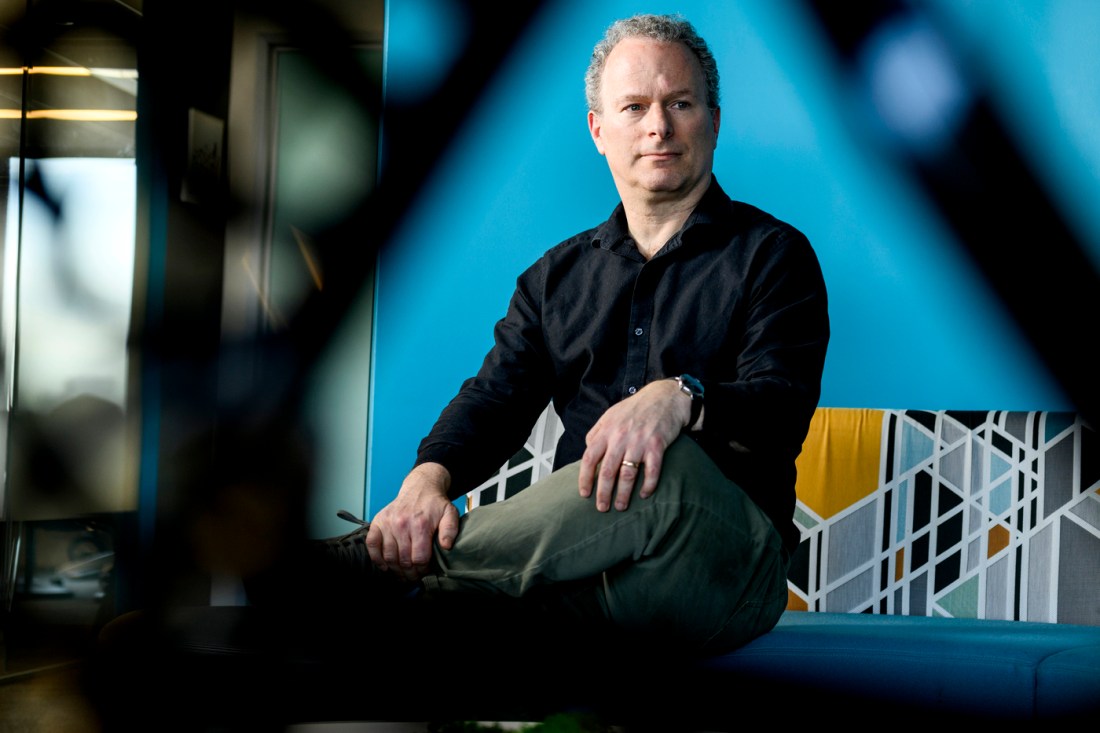

A 50-state survey co-led by Northeastern University’s David Lazer reveals that one in four Americans say they know someone who struggles with opioid addiction, while one in seven knows multiple people.

The statistics are even more alarming in poor, white, rural communities, with nearly half of West Virginians reporting that they know at least one person addicted to opioids.

The purpose of the survey was to show the indirect impact of the opioid epidemic that resulted in 107,543 people in the U.S. dying of overdoses last year, says Lazer, one of the principal investigators of the Civic Health and Institutions Project (CHIP50).

As awful as the death toll is, “that’s not the whole story,” he says. “This is the sort of pain that radiates out through the social network.”

“You have parents in their 60s who have kids addicted to opioids. You have kids being raised by parents who are addicted or siblings who are trying to take care of their suffering brothers and sisters,” says Lazer, a university distinguished professor of political science and computer science at Northeastern.

According to the survey, which was based on sampling in every state and Washington, D.C., 23% of respondents know at least one person with opioid addiction, including 3% who knew more than 10 individuals who are struggling.

The age group most impacted involved those 25 to 54. Three in 10 individuals in that age range reported knowing someone with opioid addiction, compared to about one in 10 of people older than 65 and two in 10 for those ages 18 to 24.

“Remarkably, about 20% of those middle cohorts report knowing multiple people addicted to opioids, and nearly 10% report knowing five or more such people,” according to the CHIP50 survey.

“The other takeaway is just how unevenly this falls across society,” Lazer says. “The West Virginia numbers are especially dramatic and tragic.”

The report says that state “stands out as the most affected,” with 47% reporting knowing someone with an opioid addiction compared to New York, which has the lowest rate at 16%.

Rural inhabitants are more likely than urban dwellers to know somebody who is addicted, 29% to 20%.

There are racial and education disparities, too. White respondents were most likely to answer yes to the question of whether they knew someone who struggles with opioid addiction, at 26%, while Asian Americans were less likely to respond yes, at 11%.

While opioid addiction appeared to cross partisan divides, people with a college degree were less likely to know someone who struggled with addiction (20%) versus someone with a high school diploma (26%).

“The differences are quite dramatic in large corners of American society,” Lazer says.

“A white, rural high school educated respondent, around 40 years old, in our sample would have about a 40% likelihood of knowing someone addicted to opioids,” according to the survey.

“An Asian American who is urban, around 60 years old, and college educated, would only have a likelihood of 3%.”

“It’s hitting different parts of the social network very differently,” Lazer says.

It’s no surprise that economically depressed regions of the country targeted by “pill mills” have been the most impacted, says Lazer, who sees the epidemic and its effects as reflecting “a systemic failure.”

“This was not something that had to happen,” he says. “It reflected aggressive marketing techniques directly to our doctors, who then prescribed opioids. Our systems that you would like to trust — doctors, pharmaceutical companies, the news media — all failed us,” particularly in the early days of the epidemic.

“When we think about the current crisis of trust in institutions, this is very representative of why we’re in a bad place,” Lazer says.

Featured Posts

“There’s a way in which this really helped amplify the COVID crisis,” he says. “People who have opioid addiction in their social network were also less likely to get vaccinated.”

“They’ve become skeptical of the system.”

There remains a question about the reasons for the decline in the percentage of adults who know someone addicted from 33% for ages 25 to 54 to 20% for ages 18 to 24, Lazer says.

It could be that people in the younger cohort haven’t lived long enough to know a family member, friend or co-worker who struggles with addiction, he says.

But it could also signal that restrictions on handing out opioid painkillers like candy for sports and other injuries are having an impact, Lazer says.

“People aren’t getting prescribed these opioids nearly as much,” he says, adding that social scientists need to revisit this trend in five to 10 years to get an answer.

CHIP50, which started out as the COVID States Project, has evolved into a series of surveys on vital issues of the day. Partners include Harvard, Rutgers and Northwestern universities.

It’s important to think of the opioid crisis as a social network problem rather than just focusing on the problems of individuals who are addicted, Lazer says.

“We need to think of how we can help families and close friends and how we can help them to help the people who are addicted,” he says.