“Northeastern partners in community-driven research focused on tackling housing disparities”

We have all heard stories about how high housing prices have pressured families and displaced residents.

But academics researching this trend usually do so from the outside looking in.

So the Healthy Neighborhoods Research Consortium, which includes Northeastern University, is “upending” the traditional approach to academic research in communities.

“Typically it’s the academic that goes out, seeks the grant, and then in most cases, comes to a community partner and says, ‘We have this money and we would like to work with you on this project,’” explains Patrice Williams, assistant research professor of participatory action research and a provost impact fellow at the Community to Community: Policy Equity for All Impact Engine on Northeastern’s Boston campus.

“In this case, it’s the community partners that had the funding,” Williams continues. “They had the research questions, and we solicited new partnerships with academics who had the data or capacity to work with our resident researchers on the questions that were most important to them, and produce deliverables that will help them in their advocacy efforts.”

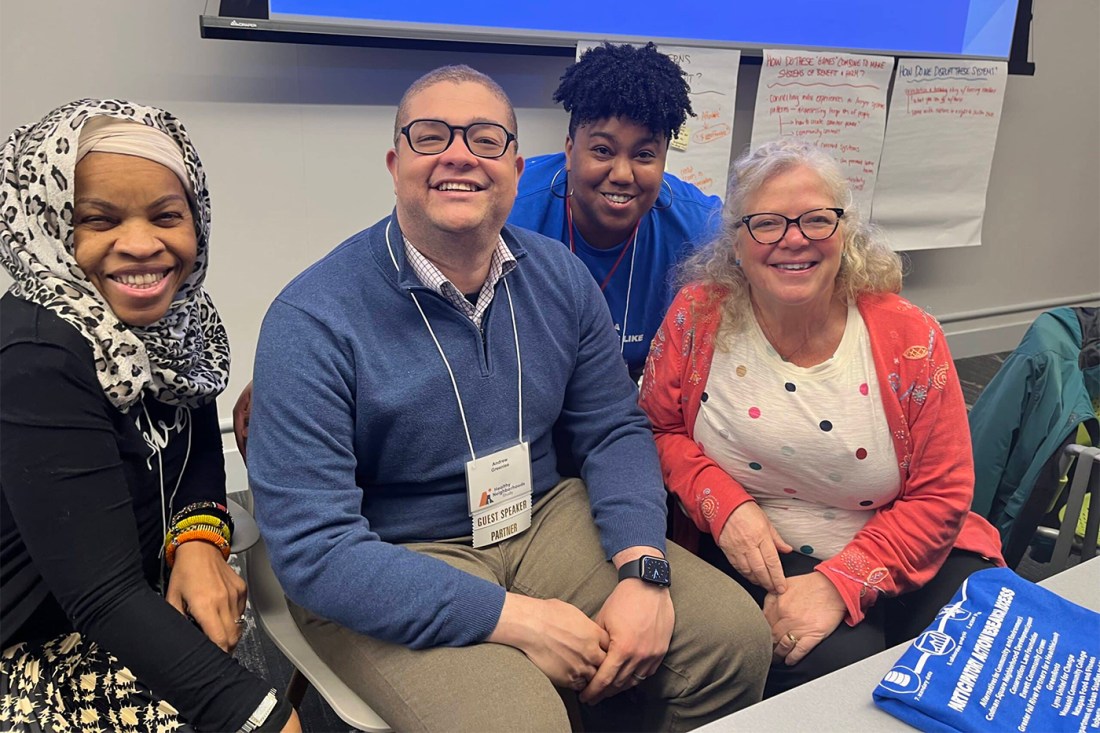

The Healthy Neighborhoods Research Consortium began in 2015 and involves nine different community-based organizations across nine different communities in Greater Boston, resident researchers, academic partners, and public agencies who work together to generate research questions, collect and analyze data and share findings to meet community-identified research priorities.

Over time, Williams says, the resident researchers have requested help.

“What they realize is that a lot of the questions they had were more systems-level questions that we couldn’t answer with only our survey and interview data,” Williams says. “We kept coming to the conclusion that we may need to seek new partnerships.”

So the Healthy Neighborhoods Research Consortium came up with a new program area called the participatory action research analytic network.

The goal for this network was to ensure these new partnerships with academics were multidimensional — these academic research teams would be using their data sources to answer residents’ questions as opposed to just answering questions of interest to the academics. In addition, the community wanted to only partner with research teams that were committed to establishing a long-term relationship.

In a recent case study, the network focused on the Greater Boston housing crisis.

Greater Boston has one of the tightest real estate markets in the United States, with limited inventory, high prices and housing production not keeping up with demand. Meanwhile, the construction that is being built often comes in the form of luxury developments in Boston and other Massachusetts cities and towns.

“The HNRC really wanted to understand what were the systems of benefit and harm influencing the real estate developments in their neighborhoods and how did they work,” Williams says.

The Healthy Neighborhoods Research Consortium selected three academic teams to work with after a proposal submission and interview process. The selected academic teams were each asked to answer the resident researchers’ questions within an eight- to 10-month period. HNRC staff, including Williams, met with the teams weekly, and then at the end of the process, the teams presented their findings to the HNRC.

Featured Posts

So, was the network successful in meeting the goals?

One of the academic teams was unable to fully answer their originally proposed research question because of missing data.

The second academic team completed its analysis, but was unable to create an interactive tool as planned within the timeframe provided, so is continuing to work with Williams. The tool will allow neighborhoods to look up corporate ownership of properties within their neighborhoods as well as the eviction history of corporate-owned property.

The third team analyzed and developed a web-based tool for residents to look up different types of subsidized housing available in its neighborhoods and the disparity between what is deemed affordable for residents and the housing options that meet their needs.

Williams, resident researchers and colleagues issued several recommendations and lessons learned about the participatory action research method in a paper published in a recent journal article.

They recommended using a participatory action research approach to identify research questions that are relevant and helpful to all nine communities, with metrics of success, interview questions, interviews and scoring of projects proposed from academics all determined by, or carried out by, the resident researchers.

Moreover, they say a key lesson learned was that it is essential that academic partners trust the expertise of resident researchers and defer to resident researchers on key decisions, especially when the project is not going according to plan.

Finally, it is possible that an academic partner may not be able to fulfill the originally proposed project. However, residents were still able to identify the silver linings.

For instance, team one didn’t answer the original question they sought, but provided a “very high-level overview” that allowed resident researchers to determine what aspects were applicable to their neighborhood and conduct their own independent research using archival data, Williams says.

“Overall, everyone found the process very positive,” Williams says. “Some aspects worked well while other areas needed further refinement.”