Google’s brand ads are a “sham” but companies have to buy them anyway, new report finds

For decades, companies have had to pay to advertise on their own keyword or risk a competitor poaching it. But a Northeastern researcher says this system only exists because Google has enough market power to say it does.

If you use Google –– and chances are you do –– then you’re used to seeing ads when searching online. But how do those ads get on Google search and, more importantly, who is paying for them? It’s easy to assume Nike pays for the Nike ads, but that’s not always the case.

Welcome to the world of brand advertising on Google, where companies often have to compete to pay Google for their own search keywords –– the term connected to a Google search for “Nike” or “Adidas,” for example –– or risk a competitor advertising on their own search results.

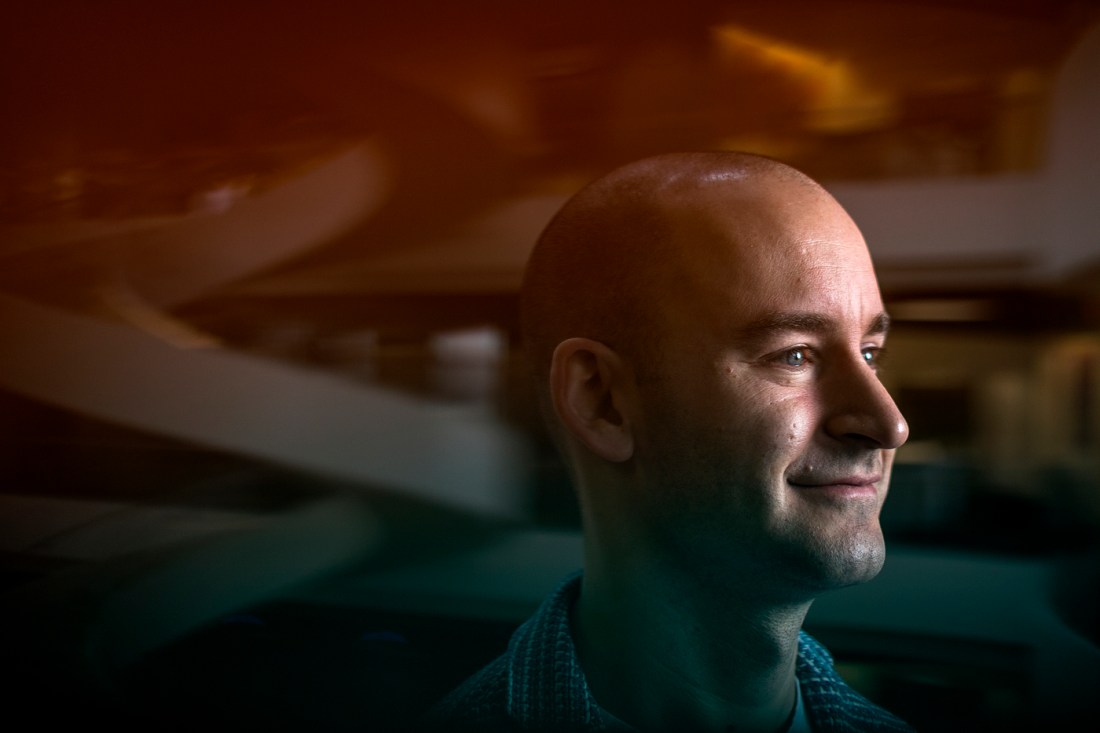

This form of ad poaching isn’t new; it’s been a practice for decades. But a recent Northeastern University study reveals that the entire brand ad ecosystem set up by Google, and replicated on other search engines like Bing and DuckDuckGo, is a “sham market,” says Christo Wilson, a professor of computer science at Northeastern, who authored the study.

“Google and the other search engines have created this market where you can advertise on navigation and brand ads, but those ads are not very effective for competitors so they’re sort of wasting their money,” Wilson says. “As a consequence, the defending companies … also have to spend money on these ads and they’re not really getting anything for it.”

To determine whether these ads are effective, Wilson recruited a group of U.S. residents and had them install an extension on their browser. The extension allowed Wilson and his team to see everything that happened in their browser windows during the study. In Google Chrome specifically, the researchers were able to pull a copy of the participants’ search results, see what they searched for, what they were shown in Google search results and whether they clicked on any of those results, including ads.

From there, the researchers used their data in combination with information about how much advertisers have to pay for brand ads to calculate whether these ads are beneficial to advertisers based on how many people click on the ads.

Featured Posts

Some people do click on a competitor’s ad when this sort of thing happens, but it’s not super frequent and the abandonment rate is very high,” Wilson says. “They clicked on the link, go to the page, but immediately come back and click on something else.”

Then why are advertisers still paying for these ads?

“That’s not a useful way for you to spend your marketing budget, but you have to because that’s the way that Google and the other search engines have designed this,” Wilson says.

These kinds of ads are a major revenue generator for Google, which makes billions every year off a practice that Wilson equates to the search giant rent-seeking from advertisers. Since Google has near total control over the online search market, it sets the terms and everyone –– advertisers and other search engines alike –– has to follow suit.

“The fact that Google is able to rent seek this way, maybe that’s not such a big issue if there was more competition in online search,” Wilson says. “But given how skewed the overall market is for online search, as long as Google says, ‘This is the policy,’ that really means that’s going to be the policy everywhere. There’s really nothing that anybody can do about that aside from lodge an antitrust complaint against Google. The whole market has to change if we want to make any headway on this.”

It might seem like the only ones being affected by this whole situation are large companies, but Wilson says there are trickle-down effects for consumers, too.

“Why do those Nikes cost $200?” Wilson asks. “Some of that is to pay for their marketing. They’re spending a boatload of money on these search ads, but those ads are not effective. Google is making a bunch of money and you’re effectively subsidizing Google through your consumer purchases.”

Regulators and lawmakers in the U.S. have raised this issue for years, which Wilson says helped create some of the momentum behind the recent antitrust case against Google. Other countries have gone a step further. In 2023, India effectively banned brand ads based on what it ruled were trademark violations.

Disallowing these kinds of ads on search would “fundamentally reconfigure a lot of the online commerce economy,” Wilson says, but he calls it a symptom of broader issues related to Google’s position in the market.

“Arguably the reason Google can continue to do this is because they have a lock on the market and there are no alternatives,” Wilson says. “But if you address that fundamental issue and enable competition in online search, then perhaps this issue fixes itself.”