Legal scholar Patricia Williams explores race, bodily integrity and law in ‘The Miracle of the Black Leg’

Patricia Williams, a distinguished professor of law and humanities at Northeastern University and a renowned scholar, releases a new book of essays.

Patricia Williams humbly compares herself to a bird that finds random shiny objects and brings them to the nest in the form of notes, newspaper clippings and photographs.

“I go after it, write a paragraph about it, and then I string it together like a necklace,” she says. “I’m completely somebody who only understands the world by writing things down.”

The result is Williams’ compelling and accessible writings that, like stained glass, join reflections on pivotal contemporary topics, critical and literary theories, empirical and sociological research, and personal narrative with classical legal doctrine.

“All of my writing is informed by my training as a lawyer,” says Williams, a celebrated legal scholar, distinguished professor of law and humanities at Northeastern University, and author of numerous books, essays and articles for leading American publications.

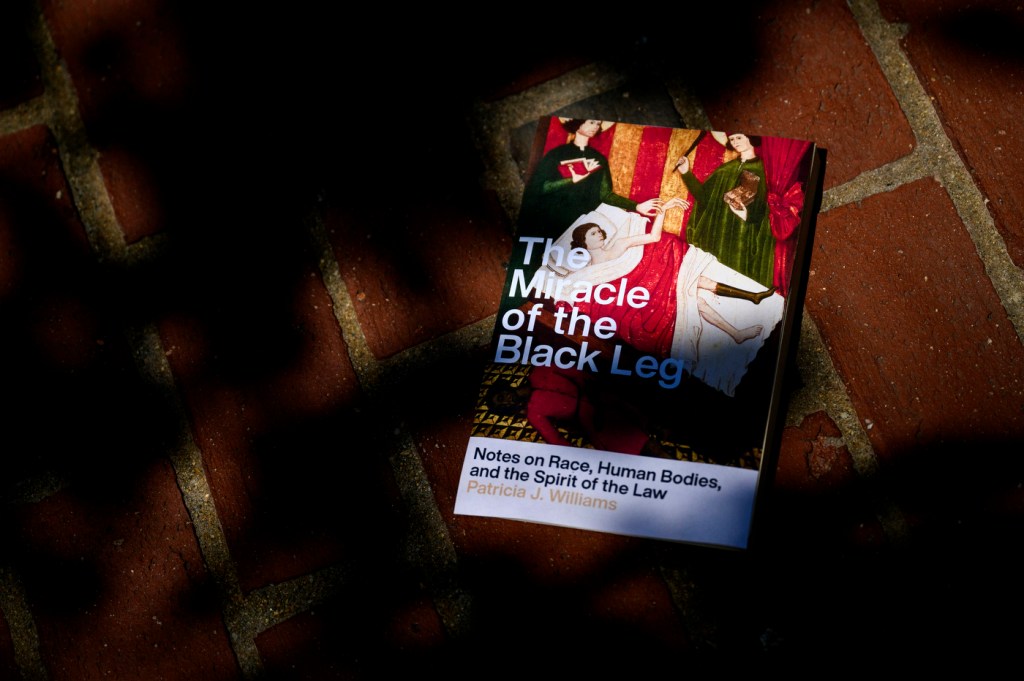

This summer, lovers of literary journalism and legal thought will be able to find out what has been on Williams’ mind recently by reading her new book, “The Miracle of the Black Leg: Notes on Race, Human Bodies, and the Spirit of Law.”

Published by The New Press and released in June, the book consists of 14 chapters, or essays, both new and partially published previously in Williams’ opinion column in The Nation magazine.

As an expert in contract law and a descendant of enslaved people, Williams continues to explore and expose the contradictions between the U.S. Constitution, a political ideal, and the jurisprudence of contract, an agreement between one side that makes the offer and another that accepts it.

“That’s something I revisit in everything I do,” Williams says. “At a moment when we’ve become more and more suspicious of any kind of regulation, even constitutional norms, my great concern is that when we enter the domain of pure contract, when everything is governed by contract, it is a very narrow moral universe of responsibility. … We really lose something in terms of responsibility to anybody other than ourselves, and this collective sense of responsibility has a role in the core values of respect, of regard for one another, of dignity.”

Featured Posts

The book opens with a chapter that has given the volume its puzzling and powerful title and front cover. It was inspired by a reproduction of a religious painting that a student brought to Williams several years ago, knowing it would be of interest to her.

The image depicted a sick white person laying on a bed with two men standing over him, one checking his pulse. The men have golden halos around their heads, while the sick man’s left leg looks black and the bedsheet is sprinkled with blood. Depending on how one’s eye wanders around the detail-filled painting, a dead body on the floor beside the bed comes last into focus. It is the body of an unconscious dark-skinned man, missing his left leg.

The image made a strong impression on Williams. It took her some time to find what exactly was depicted in the painting, she says, but it evoked a number of hypotheses and associations and even penetrated Williams’ dreams.

“It was more than just a puzzle or something that I didn’t know the history of. It had an emotional valence for me that I had to work out,” she says.

The essay touches upon objectification of human beings, one’s autonomy and ownership over one’s organs and extremities, social status of people, and contracts that protect interests of private parties versus constitutional rights.

Williams says the book accounts for those who don’t fit in, critiques the jurisprudence of contract and, implicitly, questions some recent Supreme Court decisions.

“What’s happened in the last few years … is so different from any of our past jurisprudence that I’m really worried. I really am worried because I think there’s been an abandon of the concept of precedent,” Williams says. “In the last five to seven years, there has been an inability to rely on the Supreme Court having a certain sense of continuity, and that’s worrisome.”

The book will be interesting to people who studied law, Williams says, but also to people who are concerned about such topics as bioethics, ethics of artificial intelligence, critical race theory, eugenic ideas in current political debates, issues of public good versus private concern, and putting a price on everything, including beauty.

The last chapter, titled “Gathering the Ghosts,” Williams says, is her favorite part of the book.

“It is a reflection on the thing that always inspires me,” she says.

As she prepares to donate her family’s archive to a library, Williams mulls over how future generations will see her forefathers and foremothers, what family stories she should censor and how she can “render into existence” those whose photos she doesn’t have.

Williams will be discussing her book with Régine Michelle Jean-Charles, director of Africana Studies at Northeastern, at the Frugal Bookstore in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston at 5:30 p.m. on July 18.

On July 29, Williams will be discussing “The Miracle of the Black Leg” at the Harvard Book Store in Cambridge at 7 p.m.