NBC using AI to clone Al Michaels’ voice for the Olympics. Experts says there’s room for human and AI-generated voices

Since the A.I. Michaels is trained on the recordings of Michaels’ actual calls, Northeastern experts expect Michaels’ voice double to be a very good imitation.

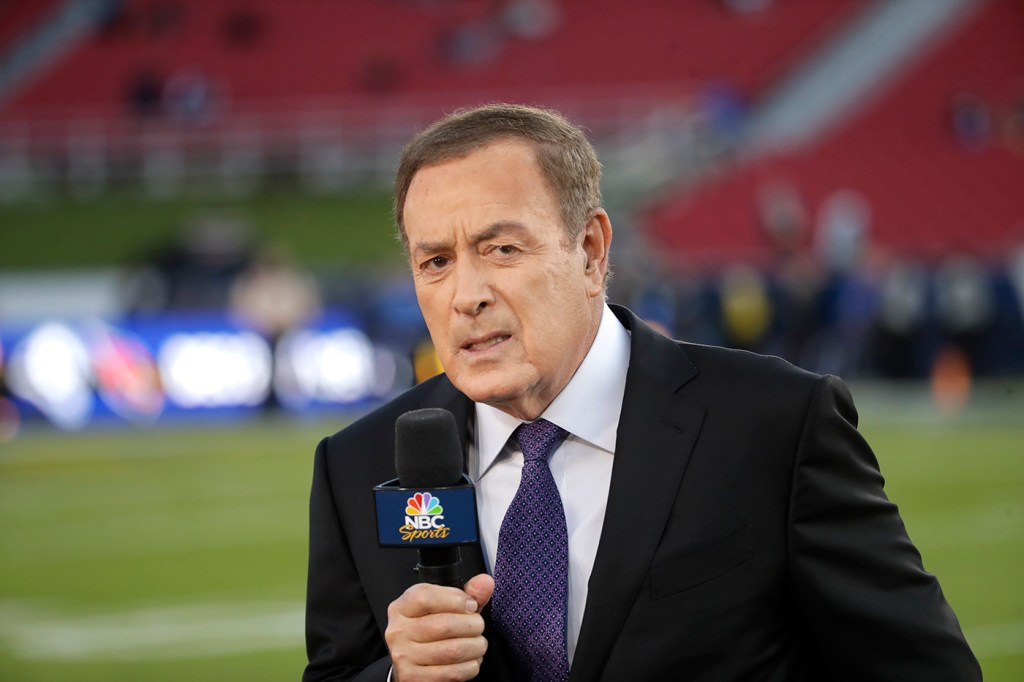

Hall of Fame broadcaster Al Michaels has been associated with the Olympic Games for more than 40 years.

Michaels announced the U.S. hockey team’s historic upset of the Soviet Union in the 1980 Winter Olympics, during which he asked the legendary question: “Do you believe in miracles?”

Michaels has called many other Olympic moments, World Series, Super Bowls, championship boxing matches and Kentucky Derbies. He has been in sports TV since 1971, including stints with ABC Sports and NBC Sports.

The 79-year-old will not be attending the Summer Games in Paris this year, but his voice will be heard around the world.

NBC, the official American broadcaster of the Olympics, announced it will use artificial intelligence to produce daily event recaps narrated by a digitally created version of Michaels’ voice. The recaps will be available on NBCUniversal’s Peacock streaming service.

The voice double that NBC is calling “A.I. Michaels” learned to talk and sound like the famous sportscaster by using the network’s vast catalog of Michaels’ past broadcasts.

Since A.I. Michaels is trained on the recordings of Michaels’ actual calls, Northeastern University experts expect Michaels’ voice double to be a very good imitation.

AI-generated voices are becoming more and more convincing and human-sounding, says Rupal Patel, a professor of communication sciences and disorders who studies speech production and speech melody for the design and development of assistive human-machine communication tools.

“If the task that you want the AI to do is different from the tasks of the data it was trained on, then I think you can tell the difference,” she says.

Large voice models are getting better at conveying changes in pitch, loudness, melody and intonation of the human voice, Patel says, especially when trained on a lot of data from a similar domain or task.

Michaels’ voice is one of a kind and worth reproducing digitally using AI if he can’t produce the recaps in person, according to Northeastern experts.

“He has this beautiful, sort of melodic and yet insightful way of viewing and broadcasting, and retelling a game through his eyes while he’s watching it,” says Dan Lebowitz, executive director of the Center for the Study of Sport in Society at Northeastern.

Editor’s Picks

“He speaks to all the beauty, power and possibility, and the promise that is the Olympics, and not just in terms of the competition of the games, but in terms of the collective betterment or a moment of peace worldwide.”

The use of AI, Patel says, will allow NBC to expand its coverage of the Olympics, which includes as many as 40 events happening concurrently. One person, she says, would never be able to narrate that many recap videos.

Patel says the media industry is starting to understand how to use AI in ethical ways to entertain and meet the needs of its customers — for example, by converting content into multiple languages.

She says that professional broadcasters and voice actors shouldn’t worry.

“I think there is space for both human and AI-generated voices,” she says. “There’s a shift, certainly, in the market, but there’s never going to be an elimination of [professional voice actors].”

John Wihbey, an associate professor of media innovation and technology at Northeastern, praised NBC for working directly with Michaels, unlike other instances where famous people’s voices were used without their permission.

The risk of something going wrong with AI-generated material in this context is low, Wihbey says, especially with good quality control and guardrails.

“I don’t see this sort of thing as a really high-risk move,” he says.

If anything, he says, it’s a good PR move.

“The networks that take on these big broadcasting contracts for the Olympics or major sporting events, they’re always trying to find ways to make sure they are relevant and talked about,” Wihbey says.

Wihbey believes A.I. Michaels could be the beginning of widespread advertising, streaming services, podcasts and other media delivered in different voices.

“We’ll see how the public tolerates it,” Wihbey says.

Rahul Bhargava, an assistant professor of journalism and art and design at Northeastern, cautions that rapid adoption of AI by media could potentially erode audience trust.

“When people see more well-produced synthetic media are they more likely to question real media?” he says.