‘Risks of nuclear terrorism are high and growing.’ New tools, alliances, renewed focus needed, group led by Northeastern expert recommends.

For roughly 80 years, the United States has managed the threat of nuclear terrorism through nonproliferation treaties, agency programs, intelligence activities, international monitoring support and more, withstanding the Cold War, the fall of the Soviet Union, and 9/11.

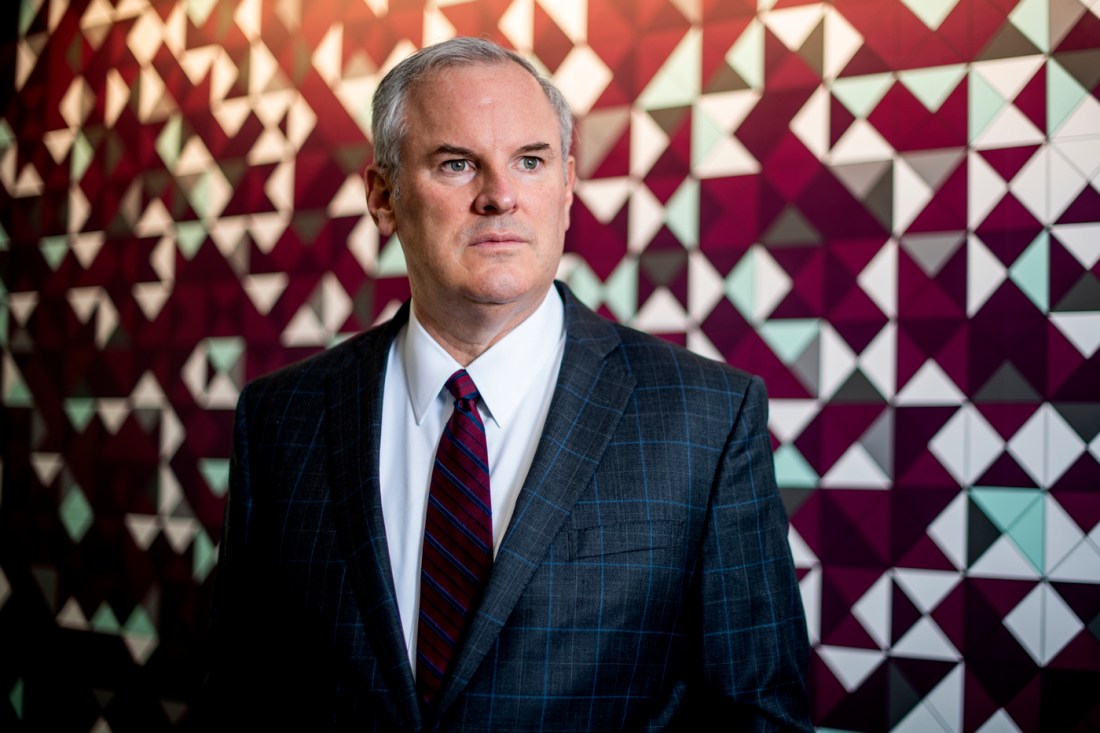

A National Academies committee led by Northeastern University’s Stephen Flynn wants to ensure the U.S. remains prepared.

“The issue of nuclear terrorism remains very much a real one, there are enormous stakes involved and the risks are high, but the issue has been falling off the radar screen of the American public over the last 15 years, and the skill set of people involved in managing it is aging out,” says Flynn, professor of political science and founding director of the Global Resilience Institute at Northeastern. “We really need to keep our eye on the ball. It was quite timely for Congress to call for an assessment of this risk and provide recommendations for staying on top of this issue.”

In the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act, Congress mandated the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Agency to work with the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine to assess the current state of nuclear terrorism and nuclear weapons and materials and advise the government on how to handle such issues.

Flynn, an expert on national and homeland security, was appointed chair of the committee in 2022. The committee released its final report on Tuesday.

The report finds that a lot has changed since the issue of nuclear terrorism was forefront in Americans’ minds following 9/11 and the buildup to the Iraq War.

“We had a war on terror after 9/11, but that didn’t succeed in eliminating the terrorsim threat,” Flynn says. “Terrorism continues to morph.”

The outbreak of the Israel-Hamas War, which occurred as the committee finalized its report, demonstrates this morphing of terrorism.

The involvement of Hezbollah as a proxy of Iran, and the involvement of Hamas — both groups are designated terrorist groups by the U.S. State Department — highlight a world where non-states and nuclear-seeking states collaborate in warfare, Flynn says.

“The designation between non-state vs. state actors is blurry,” Flynn says. “The assessment reveals we have to be focused on where those two things may overlap.”

Also “blurring” is the line between domestic terrorism and international terrorism, Flynn says.

“Particularly when you look on the far right, international terror groups are recruiting Americans into these organizations, and Americans are reaching out to extremist organizations that have terrorism elements,” Flynn says.

The nuclear world continues to morph as well.

There are now eight countries that have announced successful nuclear detonations: The United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan and North Korea. Israel is also generally considered to have nuclear weapons but has never announced it.

But as opposed to the two rival nuclear superpowers — Russia and the United States — that existed during the Cold War, a “triad” now exists, with China added to the rivalry.

“It’s hard to reach arms control agreements as a two-way relationship,” Flynn says. “It’s almost impossible to do as a triad.”

Moreover, although Russia and the United States were rivals throughout the latter half of the 20th century, Flynn says they shared the goal of limiting the supply of nuclear weapons. The demand for nuclear weapons, however, and nuclear material for civil purposes, has continued to grow. Simultaneously, there are far fewer means for managing that growth.

“We’re in a world right now where most of the control of the programs in place to manage supply and control of nuclear weapons are basically unraveling,” Flynn says.

Featured Posts

Again, recent events highlight this changing dynamic.

In May 2018, President Donald Trump withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal, Flynn notes. Then there is Russia: Flynn called the country’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine a “seismic event.”

“A nuclear power (Russia) invading a former nuclear power (Ukraine) who gave up its weapons with the promise that not having nuclear weapons would not put them at the mercy of another nuclear power,” Flynn says.

He further notes that Russian President Vladimir Putin is targeting civilian nuclear infrastructure and “is really pushing the envelope of the idea that nukes are something you leverage to advance your interests.”

It’s also not just the supply of and demand for nuclear weapons that concerned the committee. The civilian nuclear sector is enjoying a “revolution,” Flynn says, as an alternative to fossil fuel-based power generation.

But that’s not happening with the United States providing most of the oversight.

“Many new nuclear plants are going to places they’ve not gone before and this is not happening with the US setting and enforcing the rules, but being led by the Chinese and Russians with fewer security controls in place,” Flynn says. “Most of the materials that can be used to produce a ‘dirty bomb’ have always been challenging to control, and now there are more available. Even without state actor complicity, there is more risk that terrorist groups can get their hands on these materials.”

Finally, there is the question of how the United States would react to a nuclear explosion or if a so-called “dirty bomb” were detonated on the US homeland.

In an era of “fake news” and general distrust of government, would anyone even listen to local or national leaders should they warn about and try to direct civilians on what to do during a nuclear event?

“In the current context, post-COVID, there is so little trust in federal government messaging that there is the concern that managing the incident and getting life-saving information to the public is going to be enormously challenging,” Flynn says.

Moreover, it is the local municipality that will be providing the first responders to a nuclear incident. How many of them are prepared?

“The country relies on local capability to manage response to emergencies, and if it’s a nuclear terrorist attack there’s a lot to worry about,” Flynn says.

So for all these reasons — each of which has a chapter in the report — the United States has a lot of challenges.

But Flynn notes there is some hope.

“One of the big messages is as a nation we have invested a lot of effort into managing this risk over the years, and that has been — knock on wood here — a reason a nuclear incident hasn’t happened,” Flynn says. “Let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater — we’ve got a lot of capability, let’s stay on top of it.”

How can we do so?

The committee does not provide a specific budget figure, but recommends that Congress provide continued and increased funding for nuclear-deterrent activities. The report also recommends better coordination among the various government agencies — for example, beyond the Department of Defense, Flynn mentions the Coast Guard, Department of Homeland Security, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Department of Energy, and more — that each contribute to protecting the United States from a nuclear incident. Finally, the report recommends that these agencies adopt new technology and tools to mitigate the nuclear terrorism threat.

“We’re not saying to the government that this is something they’ve neglected,” Flynn says. But Congress has to continue its support for it, and we have to continue to do our due diligence.”

“There is a lot of knowledge we have about managing the nuclear risk, as we have been doing it for decades, but there are also new tools and there’s a lot of ways to update our response from the Cold War days,” Flynn continues. “This is something we should be worried about. … But take a deep breath, we have been managing this risk since the dawn of the nuclear age, so let’s draw on that experience, and there are new technologies and ways we can deal with this risk that are better aligned to the world we are living in.”