Juneteenth panel at Northeastern examines the past, present and future of the reparations movement in America

Juneteenth, also known as Freedom Day and Emancipation Day, is celebrated annually on June 19 to commemorate the end of slavery in the United States.

The conversation about reparations for slavery in the United States is not new. Yet, still, many don’t understand what reparations are or what they could be.

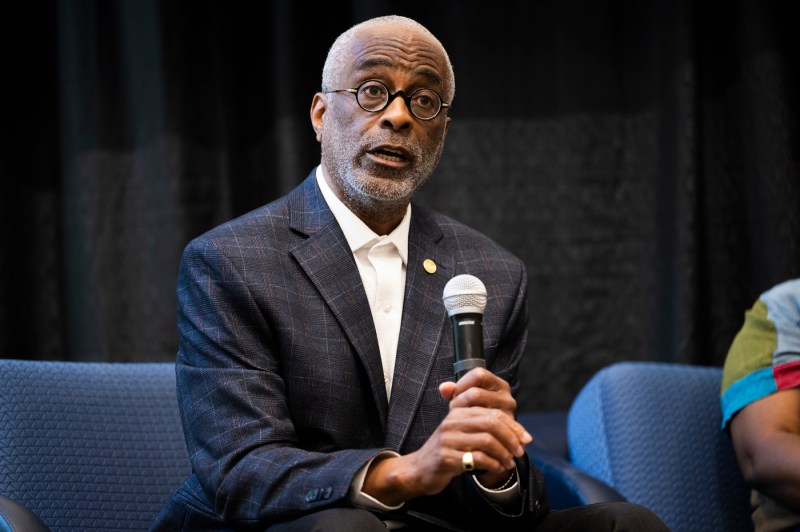

A Northeastern University panel discussion, “Understanding the Reparations Movement,” held in advance of Juneteenth examined the history of the cause and what’s being done today at the federal, state and local levels.

Juneteenth, also known as Freedom Day, Emancipation Day and Black Independance Day, is celebrated annually on June 19 to commemorate the end of slavery in the United States. The day was recognized as a federal holiday in 2021.

While the topic of reparations can be divisive, Deborah Jackson, a member of Northeastern’s Reparations Research Team and managing director of the Center for Law Equity and Race, said the point of reparations is to raise everyone up.

“There’s a West African concept called ubuntu: ‘I am because you are,’” Jackson said. “It talks about the interconnections that we all have. Generally in the U.S. and western culture, it’s based on the individual as opposed to the collection.

“I think there’s an opportunity here in our work to have more of a focus about the collective whole,” Jackson said. “Together, we all thrive and do well as opposed to being in competition.”

In addition to Jackson, the panel was made up of speakers involved in the reparations movement in Boston, including Joseph Feaster, a member of the city’s Reparations Task Force, and Elizabeth TiBlanc, vice president of arts and culture at Embrace Boston, which created a harm report looking at the legacy of slavery on policies in the city and state.

They were joined by Ashley Adams, an assistant adjunct professor who is part of Northeastern’s Black Reparations Project, and Kyera Singleton, who is part of Tufts University’s Reparations Research Team.

The discussion was moderated by Regine Jean-Charles, director of Africana Studies at Northeastern, the dean’s professor of culture and social justice, and a professor of Africana studies and women’s, gender and sexuality studies.

The panelists discussed the modern reparations movement and where it got its roots.

There have been efforts to consider reparations on the federal level since 1989 when Rep. John Conyers of Michigan proposed a bill that would study the idea of reparations for slavery, Feaster said.

Cities like Evanston, Illinois, have actually begun the process of making reparations, while Boston is beginning the process with a task force that is focussed on the role the city played in the transatlantic slave trade.

There are at least 26 states that have local advocacy efforts around reparations, Adams said. She added that in California a task force looking at reparations identified 12 areas of harm where the work of reparations can begin and put forward three bills to support future efforts.

Featured Posts

TiBlanc explained that harm reports look at what harm has been done by slavery so that governments can properly address this in their reparation policies. And these policies don’t need to be solely financial, Adams said.

“We think about the way that decisions are being made,” TiBlanc said. “For example, we think about redlining in Boston, we think about segregation in public schools in Boston, and how we still see all the remnants of those policies. I think the first thing that comes to people’s minds (when it comes to reparations) is money. What’s really important is to continue (to consider) what repair looks like.”

But, Feaster said, reparations are an uphill battle, pointing out that the Oklahoma Supreme Court just upheld a lower court’s dismissal of a lawsuit asking for reparations for the survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre. The event left 300 Black people dead at the hands of a white mob.

“If Tulsa can’t get reparations, then the job that each of us have here … is going to be a difficult process,” Feaster said. “This is not going to be an easy task. We’re going to have to do a number of different things.”

Richard O’Bryant, director of the John D. O’Bryant African-American Institute at Northeastern said the panelists helped highlight the work being done not just in Boston, but elsewhere throughout the country.

“Understanding what reparations means is an essential part of bringing the historical impact of slavery to some achievable restoration,” he said. “It really is important for us in the academic community to really continue to talk about this and help us move it along to a point where we can come up with some real solutions.”

Audience members, including community activists, were impressed by the depth of information provided by the panelists.

“It answered a lot of questions I had about reparations and what we’re doing to move forward in those plans,” said Takiyah Watson, an intern at the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project. “It (showed me) the things that have and haven’t been successful. I think that was really good to know.”

“I’m coming as someone new in the space and I think everything everyone said was really inspiring,” added Halle Snell, another CRRJ intern. “I liked how they were coming at it from a variety of perspectives. The intersection of all those disciplines can help us create a really big picture of operations, but also focus on more specific areas.