Meet the Northeastern co-op helping to upgrade the world’s largest particle accelerator at the European Organization for Nuclear Research

For Christian Bernier, it started with videos he saw as a kid on popular YouTube channels like Minute Physics.

Bernier has always been interested in science, so he found topics around the fundamentals and building blocks of the world to be particularly fascinating. He quickly developed an “insatiable desire to know more about the universe, physics and how the world works,” he says.

Time after time, the work being done by the European Organization for Nuclear Research, or CERN, was brought up in those videos. As a kid, Bernier had no idea what CERN was about, but he was intrigued.

“They’d mention CERN offhandedly, and I was like, ‘What is this thing they keep mentioning?’”

So, Bernier did some digging and fell in love with the research center’s mission and work — so much so that when it was time to decide on an area of study at Northeastern, Bernier decided to pursue a combined major in computer science and physics.

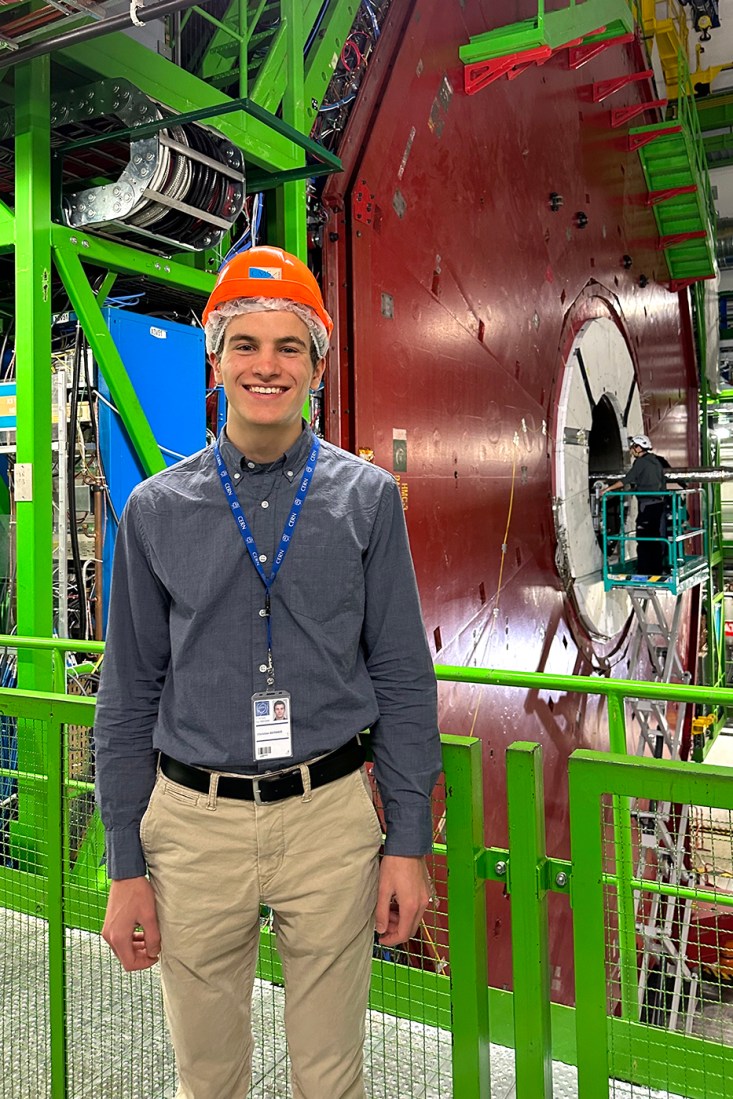

Now the incoming fourth-year Northeastern student is helping CERN advance that mission as a particle physics research assistant as part of his co-op at the Geneva-based organization.

“One of the main reasons I chose my combined degree is to see how computer science is used in physics research,” he says. “I actually had CERN in mind when I chose my degree, so it’s cool that I ended up here and see what that’s like.”

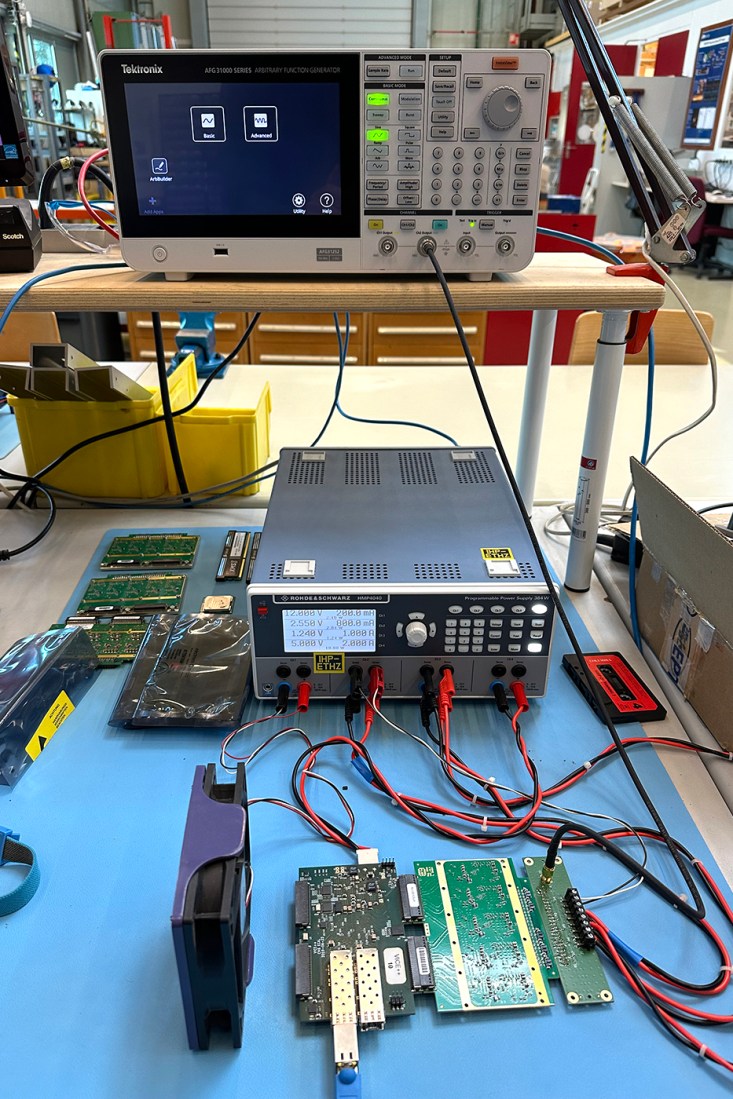

Bernier has been tasked with helping develop software to ensure circuit boards being installed on one of the detectors connected to the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world’s largest particle accelerator, can function long term without overheating.

Featured Posts

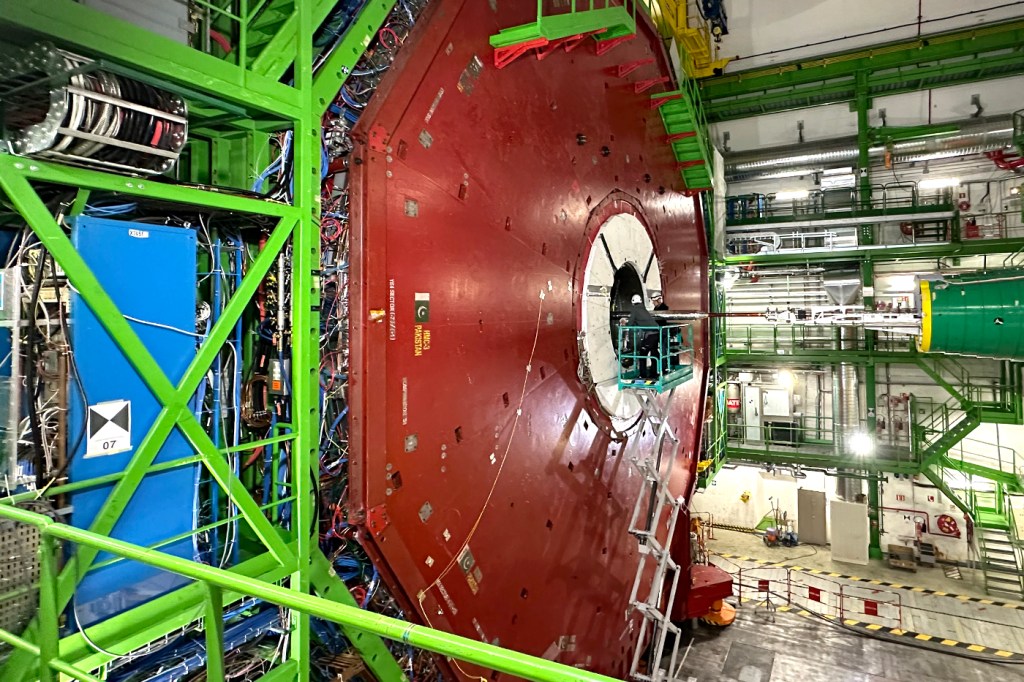

LHC is a 17-mile underground tunnel that consists of multiple parts. Bernier is specifically conducting work on one of the four main detectors around the collider called the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS). The CMS is used for a range of different projects including research on the fundamentals of how matter works and the exploration of extra dimensions, according to CERN.

“They’re currently working on upgrading the accelerator, and so they need to update or upgrade all the detectors as well, ” Bernier says. “So I’m working on the upgrade of CMS, specifically one layer called the electromagnetic calorimeter, and what I’m doing specifically is writing software to test the physical circuit boards that are going to go into the detector.”

The CMS detector is about three-stories tall and the specific layer Bernier works on consists of about 12,200 individual circuit boards, he says. Bernier is currently conducting testing for new circuit boards that are still in the process of being designed.

“I’m working on a system for cards that doesn’t even exist yet, because once they do exist, we need to have them up and running immediately so we can keep up with supply,” he says. “The goal is for them to be reliable. Once they are in the detector, they are a total pain to get out again.”

The cards that are being used for testing are relatively small at about 7 inches by 4 inches and are being placed in simulated environments where they are being run at about 70 degrees Celsius (158 degrees Fahrenheit). About 500 cards are being tested at a time.

“You can do calculations and simulations to determine that if you run them at a certain temperature for a certain amount of time and power cycle them a certain number of times, that’s equivalent to a year of running,” he says. “That’s what we are trying to do with the system to get them over the point where they would fail early on.”

Bernier is taking advantage of his computer science background to learn programming languages like Python to help develop these systems, he says.

“It’s really a small portion of CERN that I’m working on,” he says. “It’s one piece of one system of one part of one detector of one accelerator. It’s really very focused, but I think it’s at a good level to be at because I really understand what I’m doing at this point.”