How will Google’s AI Overview impact its ad revenue? ‘They might be cannibalizing their own revenue stream,’ expert says

John Wihbey, an associate professor of media innovation and technology at Northeastern, thinks Google’s cash flow from ads will take a hit — at least in the short term.

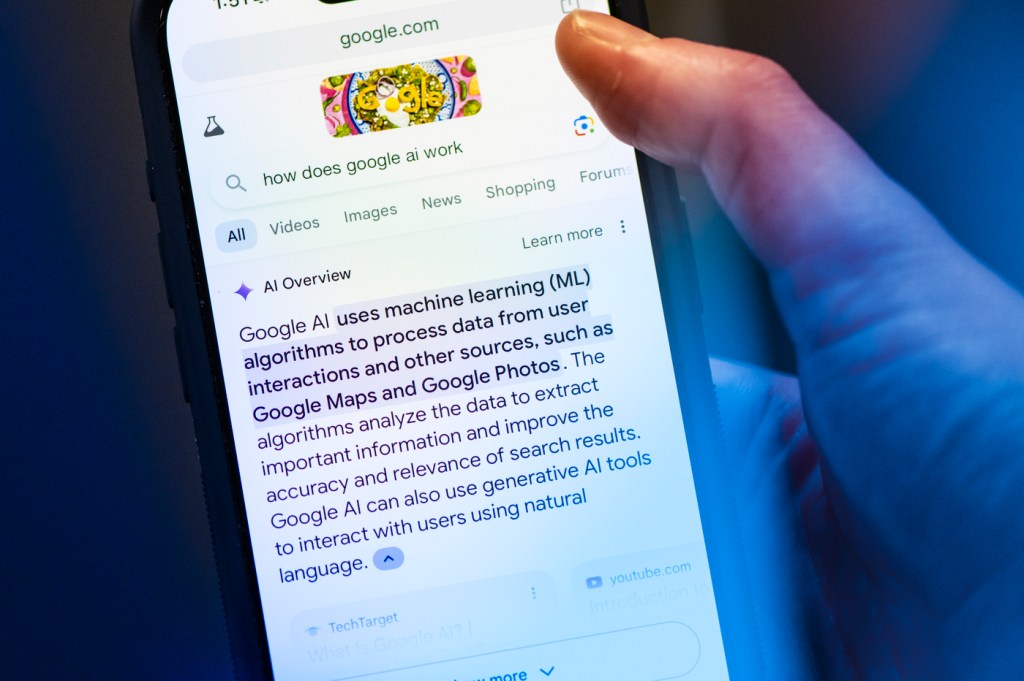

Google recently unveiled its overhauled search engine that includes several features powered by artificial intelligence. One of those features, AI Overview, provides users with more direct answers to their queries.

Some would say that Google used to be a search engine, and now it’s a search, answer and problem-solving engine — and much more — all without having to navigate away from the home page.

“What’s the cure for the common cold?”

Google previously may have directed its users to hundreds of sources such as the Mayo Clinic, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or even GoodRx. It’s now using AI to scrape those sources and provide answers devoid of attribution.

Google does provide some links under its new AI Overview, but those links may not be where the answers came from.

So why is Google doing this?

The leap into generative AI will certainly help Google compete with the likes of OpenAI, creator of the chatbot ChatGPT, and Microsoft, experts say. What’s not clear is how Google will make money from its new technology.

In 2023, Google generated $237.86 billion in advertising revenue from its Google Ads platform that allows businesses, small and large, to buy digital ads for products and services.

Google ad revenues have more than doubled since 2018.

So, if the AI Overview is keeping more users on Google’s home page, and pushing fewer users to web pages — where the lucrative ads are housed — won’t Google’s ad revenue take a big hit?

John Wihbey, an associate professor of media innovation and technology at Northeastern University, thinks it will — at least in the short term.

“It looks like they might be cannibalizing their own revenue stream,” Wihbey says.

Google’s AI Overview and de-emphasis on links could reduce traffic to websites by about 25%.

“Especially for web publishers who depend on traffic, there could be some absolute falling-off-a-cliff dynamic,” Wihbey says.

Businesses and publishers may start providing new data layers on their websites to be detected by the AI search engine, Wihbey says, and bid at an auction for the opportunity to be displayed in the search results.

Search engine optimization, or SEO — using keywords and phrases to cause content to rank higher on a Google search — is also evolving, Wihbey says.

“I’m sure there’ll be a whole new industry about AI model SEO,” he says. “It may end up being that websites, businesses and publishers provide new data that then feed models in certain ways.”

Google says it will eventually connect ads to its AI Overview, which is expected to be rolled out to about 1 billion people by the end of the year.

But users might not want to read or trust the AI Overview if they view it as essentially a paid advertisement, Wihbey says.

But AI Overview isn’t without its flaws — lots of them, in fact. Social media is abuzz with examples of Google suggesting people eat rocks or put glue on pizza, and that former President Barack Obama is Muslim.

Featured Posts

It’s hard to tell, Wihbey says, if the AI technology introduced by Google was fully ready for release.

Perhaps, he says, Google is doing what many startups — including Twitter and Reddit in the 1990s — did.

They launched without a reliable revenue stream, Wihbey says, and hoped to figure it out while building an audience of hundreds of millions of users.

“Well, Twitter never figured it out,” he says.

Wihbey directs Northeastern’s graduate programs in media innovation and data communication, journalism and media advocacy. He’s also served as a research consultant for Twitter.

For the record, he doesn’t think Google’s search engine and AI strategy — attract an audience first and figure out how to make money later — is a bad idea.

After all, Wihbey says, if Google doesn’t maintain its position as the leading search platform in the world, it will eventually lose its ability to connect buyers and the sellers anyway.

“I think a new architecture is starting to emerge,” Wihbey says. “The canonical worldwide web we’ve known is just going to evolve to have new kinds of data layers that will feed these [AI search] models.”

As Google’s AI Overview demonstrates, search is becoming more complex, Wihbey says. Users are asking questions while expecting more complex answers, for example, about health planning, business and family.

“There is a push to make AI more agentic,” Wihbey says, meaning that AI is taking on the role of helping people solve complex problems and anticipating users’ needs.

“You can imagine people starting to use agents to do search, and then the search AI models interacting with agents,” Wihbey says.

Google, however, has a clear competitive advantage over OpenAI and other competitors, Wihbey says, because its parent company, Alphabet, owns over 250 companies including Google Chrome, YouTube and Adsense, Google’s ad vendor for advertising.

So, Google can incorporate AI models into several products, Wihbey says, and condition people to do certain things while collecting data that will be useful.

At the same time, other AI platforms have been working with news outlets to use their content for its AI models.

Last week, OpenAI signed a deal with Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp., which owns the Wall Street Journal and New York Post in the U.S., and the Times and Sunday Times in the U.K. OpenAI previously signed a content deal with the Financial Times.

Similarly, Google may end up paying “every imaginable publisher,” Wihbey says, to feed its generative AI models, including AI Overviews.

“I think these data licensing agreements, they have to get more and more lucrative over time,” Wihbey says.