Do you know where your burger comes from? Memorial Day cookout attendees often unaware, food safety expert says

Northeastern professor Darin Detwiler says ground beef can come from up to 400 heads of cattle — another reason to cook that burger thoroughly.

Whether the hamburgers being served at your Memorial Day cookout are 90% lean or 30% fat, they likely consist of meat from multiple herds of cattle, not just one cow or bull.

The mixing of animal parts in ground beef increases the already considerable risk of food-borne illness caused by E. coli, says Northeastern University food policy expert Darin Detwiler.

Properly handled and prepared, hamburgers are a welcome addition to a cookout or dinner table, he says. “The big concern here is that people don’t understand food safety and minimum cooking temperature.”

One package of ground beef, many cattle

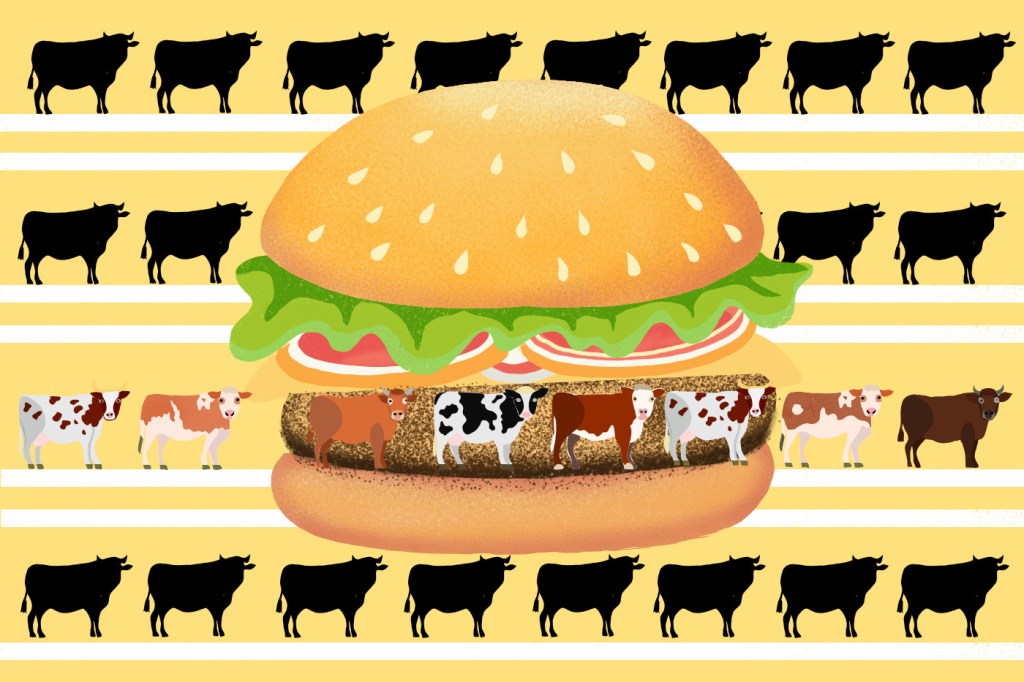

“Most people are not aware that ground beef purchased at a store is not from one animal,” Detwiler says.

“It typically comes from centralized, batch operations that can result in meat from up to 400 heads of cattle being mixed together. They take batches of meat parts at different fat levels and grind them up in these huge, big vats.”

“It’s like a math equation,” Detwiler says. When customers go to the grocery store, they see packages marked 90/10 parts lean to fat, or 70/30.

“But this process can spread E. coli bacteria from a single piece of meat throughout an entire batch of meat,” he says. “The entire batch is contaminated.”

Why ground beef has a higher E. coli risk

Even without being made up of different animals, ground beef is more susceptible to E. coli contamination than whole beef products such as steaks, Detwiler says.

That’s because whole slices of beef typically get exposed to E. coli only on the surface through contact during the butchering process with a cow’s intestines or the animal’s hide, he says.

The bacteria remains on the surface of the meat, where it is killed by cooking or searing, Detwiler says.

But the process of grinding beef brings pathogens on the meat’s exterior surface into the middle of the mass of beef, Detwiler says. That means leaving a hamburger pink or raw in the middle risks exposure to E. coli that hasn’t been killed in the cooking process, he says.

The risk of E. coli contamination in ground beef has led to two company-ordered ground beef recalls within the past five months, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the federal agency in charge of inspecting meat, poultry and eggs.

In the latest announced May 1 by the USDA, Cargill Meat Solutions issued a recall of more than 16,000 pounds of raw ground beef shipped to Walmart locations in 11 states and Washington, D.C.

What are the symptoms of E. coli

E. coli symptoms include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and fever, Detwiler says.

“The CDC estimates that each year 48 million people get sick from a foodborne illness, 128,000 are hospitalized and 3,000 die,” he says.

“It is typically the most vulnerable — the very young, the elderly, those with compromised immune systems and those who are pregnant — who become hospitalized or worse.”

In the 2023 Netflix documentary, “Poisoned,” Detwiler talked about how the loss of his 16-month-old son, Riley, to an E. coli outbreak linked to Jack-in-the-Box hamburgers in 1993 changed his life and led to him becoming a food policy safety expert.

Featured Posts

“I have re-lived that event through a seemingly endless series of similar events over the past 31 years,” he says. “Each new outbreak or recall is a stark reminder of the work that still needs to be done and the continuous threat posed by foodborne pathogens.”

How to safely prepare ground beef

After shunning red meat for a while, Detwiler started eating it again but grinds his own beef at home to reduce the chances of a pathogen problem.

Whether hamburgers are store bought or home ground, Detwiler advises people to cook them to an internal temperature of 160 degrees Fahrenheit (71 degrees Celsius), which he says has been proven to kill E. coli in ground beef.

Avoiding cross contamination by using separate utensils, cutting boards and plates for raw beef is also key, as is storing ground beef in the fridge or freezer promptly after purchase to inhibit bacterial growth, Detwiler says.

And don’t use the same platter for raw patties and cooked burgers, he says. “This simply re-contaminates the meat.”

Detwiler also advises consumers to be aware of recalls, check product identification numbers and other information included in the recall and to store the recalled item in a plastic bag or in a separate area of the freezer or fridge before disposing of it or returning it for a refund.