Researchers are translating ‘whale-speak’ — accents included — and this Northeastern network scientist is leading the way

Giovanni Petri, a professor in the Network Science Institute at Northeastern University in London, has been part of a team looking at how communication changes among sperm whale clans whose territories overlap.

LONDON — In the Disney movie “Finding Nemo,” the blue tang sidekick Dory — voiced by Ellen DeGeneres — says she doesn’t speak whale, only to go on and do exactly that.

Now humans want to get in on the act, looking to record and monitor sperm whales as part of an ambitious project to understand what they are saying to each other.

Giovanni Petri, a professor at Northeastern University in London, is one of the founding members of the Cetacean Translation Initiative — or Project CETI for short — that has the potential to translate whale-speak.

Now the lead network scientist on the project, Petri is working with a team of marine biologists, cryptographers, linguists, roboticists, engineers and underwater acousticians from more than 15 research partner institutions across nine countries.

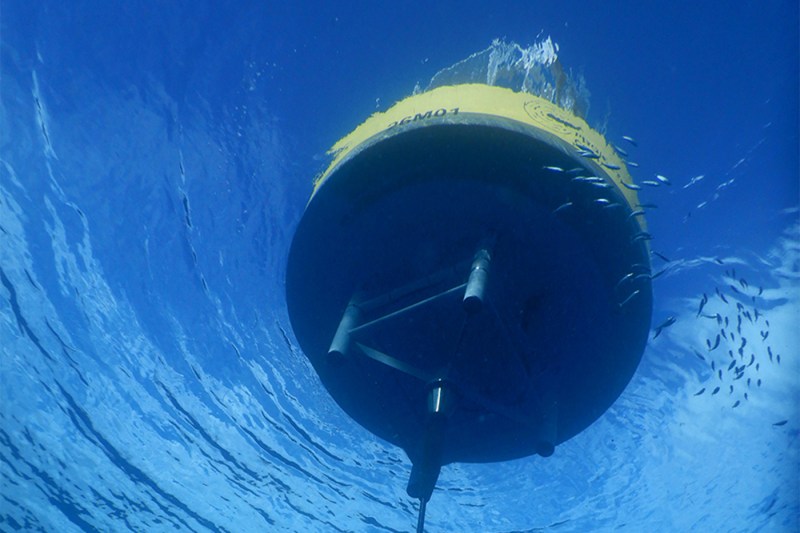

Together with artificial intelligence, they are trying to make sense of what is being said underwater by sensitively tracking and recording sperm whales using boats, buoys, drones, cameras and other technology.

As the field workers make their recordings of sperm whales in the waters around the island of Dominica in the Eastern Caribbean, Petri and his team have been preparing tools and models using already-available data to map potential networks and patterns in their communication.

In a paper published May 14 in the eLife journal titled “Evidence of social learning across symbolic cultural barriers in sperm whales,” Petri and his seven co-authors say a model they have produced may have helped establish a breakthrough.

The peer-reviewed paper provides evidence that clans of sperm whales share similarities in so-called “vocal style” when in close proximity or even in overlapping territory, potentially hinting at intercultural learning among whales.

The research suggests it is possible that sperm whale clans occupying the same region pick up the vocal styles of their neighbors.

The findings follow on from a separate paper published only days before by CETI-associated experts that suggested there is a type of sperm whale phonetic alphabet.

Sperm whales are complex creatures that live in matriarchal and organized societies, and have been found to share dialects and hold strong multigenerational family bonds.

These massive mammals — males can reach up to 18 meters, or nearly 60 feet, in length, almost as long as a bowling lane — have the largest brains of any species and converse with each other using an aquatic type of morse-code that involves click-based patterns. These rhythmic sequences of clicks are known as codas.

Scientists have discovered that sperm whales belonging to the same tightly-knit clan will talk with their own style — a form of clan “accent” — using what experts refer to as “identity codas.”

What Petri’s research has found is that, when looking at so-called “non-identity codas,” which make up 65% of sperm whale signals, whale clans communicate in a vocal style that is “more similar” to nearby clans.

The Italian’s team applied a new analytical approach that focused on how sub-coda structure differentiates from clan to clan, effectively describing how clicks are put together in time to form codas. This in turn was used to define the vocal style for a group of whales.

By quantitatively comparing the vocal styles of different clans, they found that the vocal styles of non-identity codas became more similar with clans whose territories overlap, while no effect was observed for the identity codas of those clans.

This, the paper argues, “suggests that geographic overlap induces vocal styles to become more similar between clans, without jeopardizing each clan’s acoustic identity signals”.

Petri and his cohorts initially built their analytical model using a small set of data from two small clans based in the waters off Dominica, giving them a feeling that “something was going on but we couldn’t really prove it.”

It was only when handed a larger selection of data from at least 10 clans from across the Pacific Ocean that they were able to test it properly.

“We had that [the model], we had developed the data, we could differentiate the families, we could do many different things but we couldn’t do this large scale comparison between clans as we had no spatial dimensions,” Petri said.

“So when this Pacific data emerged, all of a sudden we could do that and we actually did it in an afternoon because everything else was ready,” he said. “That is when we started feeling that there was something very important here.”

It was then time to bring in the experts, including those who had provided the original recordings of the two Dominica clans.

“My team is mostly mathematicians and physicists, so we can only go so far,” Petri explained. “We see something that we think is true but then when we bring in (a field biologist who) could say that what we were seeing was actually meaningful.”

The question now is, does this breakthrough help the brains behind CETI to understand what the whales are saying to each other?

“No! But we would love to,” Petri said.

Editor’s Picks

He said scientists think that identity codas, while key for clans in identifying their members, “don’t really convey meaning” and that, with his and his colleagues’ new paper being one of the first to focus on non-identity codas, there needs to be more research on what those communications mean.

But with sperm whales being huge creatures that can dive to depths of 2 kilometers during their hunt for prey, tracking their movements can prove a challenge.

“Even just recording these animals is difficult,” Petri said. “Now imagine adding something more, which is having sound, communication and their behavior.

“The important thing for us would be to be able to say, ‘They are saying this when they do this,’ or ‘Someone says this and then this behavior appears.’” he said. “At that point, you can start actually making the connection. But that is very hard to do.”

Petri’s next project has already started after CETI scientists witnessed up close and personal in summer 2023 a rare event — the first scientific record of a sperm whale birth since 1986. CETI, which received $33 million in funding from The Audacious Project to get started, is due to publish its findings about the birth next year.

“We got very lucky last summer because we spotted a very large group of animals and it was weird behavior because they were staying at the surface,” Petri said. “And then eventually they were moving around, there was some blood coming out and then there was a birth event.

“Now we are working on that data. We have the video footage and we are trying to work out if we can understand the social interactions that they were having at that moment. What was happening, who was the mother, was it a communal thing? We are getting there.”