RFK Jr. says a parasite

ate part of his brain. Do parasites

actually ‘eat’ human tissue? And how

do they end up in the brain?

How do parasites, such as tapeworms, get into the brain in the first place? Scientists say they can — but that they “eat” human tissue is something of a misnomer.

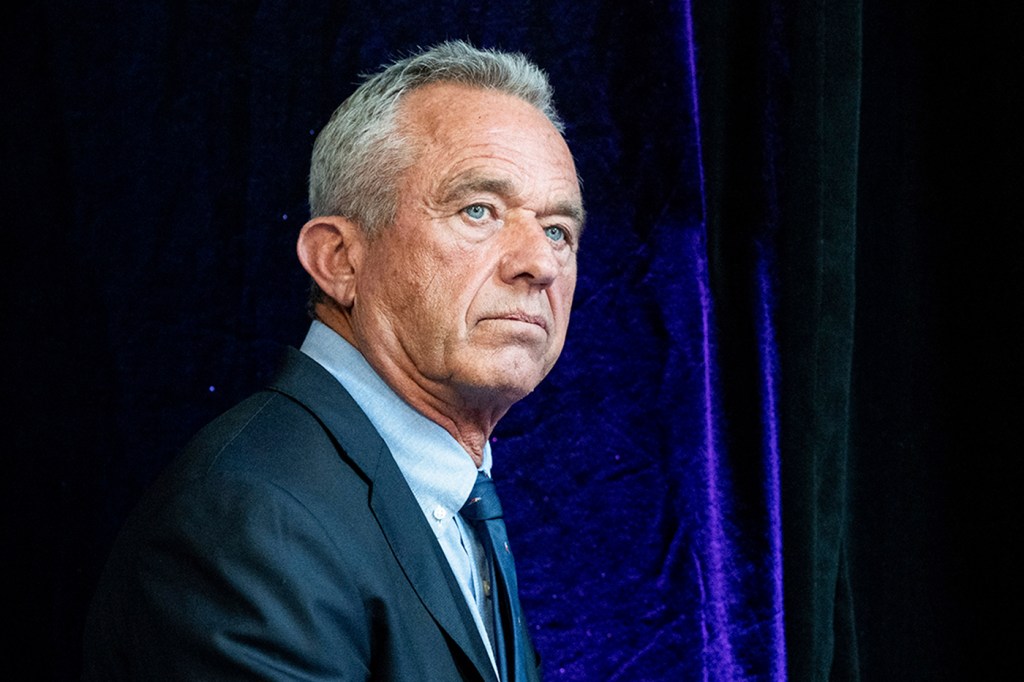

Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s campaign says a parasitic worm the presidential candidate contracted years ago while traveling outside of the United States ate a portion of his brain, then died.

How do parasites, such as tapeworms, get into the brain in the first place? Scientists say they can end up inside of a person’s skull — but that they “eat” human tissue is something of a misnomer.

Lori Ferrins, a research associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Northeastern University, studies neglected parasitic diseases. She says it’s possible that inflammation caused by a parasitic illness could make it easier for organisms to slip past the membrane shielding the brain, known as the blood-brain barrier.

“Amoeba can work their way through the blood-brain barrier and tapeworms are also known to migrate into the brain,” Ferrins tells Northeastern Global News.

Featured Posts

“During an infection, the inflammation can make the blood-brain barrier a little more porous, potentially enabling them to make their way through.”

Parasitic organisms include flatworms, roundworms and thorny-headed worms, or spiny-headed worms, according to Healthline.

News of RFK Jr’s parasitic issue, disclosed in a 2012 deposition taken during divorce proceedings from his second wife, comes amid public scrutiny on the health of Joe Biden, 81, and Donald Trump, 77 — the two oldest politicians to serve as president.

A spokesperson for the independent candidate, who is 70, told the Washington Post his health “issue was resolved more than 10 years ago, and he is in robust physical and mental health. … Questioning Mr. Kennedy’s health is a hilarious suggestion, given his competition.” The spokesperson said Kennedy contracted the parasite while traveling “extensively in Africa, South America and Asia in his work as an environmental advocate.”

Michael Pollastri, a senior vice provost and professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Northeastern, says that tapeworms “can end up in the brain in severe cases,” noting that it’s rare.

Parasitic diseases are not common — and in the U.S. they are even rarer. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of new cases in the U.S. each year is “probably less than 1,000.” Worldwide, Ferrins says cases are significantly under-reported.

The primary cause is consuming raw or undercooked pork, Ferrins says. Parasitic infection tends to occur in unsanitary environments, when pigs are exposed to human excrement, consume the fecal matter and are then consumed by humans.

“These infections are more common in countries with poor hygiene and sanitation, and eating undercooked meat leads to human infection,” Ferrins says.

Parasites — so-named because they “feed” off of a living host — don’t actually “eat” human tissue, Ferrins says. If parasites aren’t actually eating through human tissue, what are they doing once inside the body?

“In an intestinal infection, the head attaches to the inside of your intestines and absorbs nutrients from the food digesting there,” Ferrins says. “So, I think it would be fair to say that a similar process may have occurred in [RFK Jr.’s] situation — the worm is absorbing nutrients from the body or brain, and then it will grow and expand.”

Ferrins clarifies that the worm “isn’t actively eating tissue, rather causing atrophy through pressure of the surrounding tissue as it grows.”

“When a tapeworm resides in muscle and brain tissue and eventually dies, it actually starts to calcify,” Ferrins says.

Ferrins continues: “That cyst is what has calcified and is now dead.”

She adds that what RFK Jr.’s doctors may have seen on the brain scan was “actually a calcified cyst.”

Steps to prevent infection include being cognizant of personal hygiene and food safety protocols, such as cooking meat to an appropriate temperature. On a global scale, however, Ferrins says prevention also requires public health interventions, specifically improved sanitation practices.