This Northeastern co-op is helping uncover the secrets of North Atlantic right whales and Adelie penguins in Antarctica

A co-op with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute has third-year Northeastern University student Haley Benjamin observing right whales off the coast of Massachusetts, counting penguins in Antarctica via drone and getting closer to her goal of becoming a marine biologist.

“I’ve just always known that I need to work with animals,” says Benjamin, who is working at WHOI’s Marine Mammal Remote Sensing (MARS) Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

The diverse range of marine animals and opportunities for doing research on them inspired her to major in marine biology at Northeastern.

“I feel marine animals are so underappreciated compared to land animals,” says Benjamin, who is from Taunton, Massachusetts. “There are so many unknowns in this field that there is a lot of room for questions to be answered.”

Experience with right whales

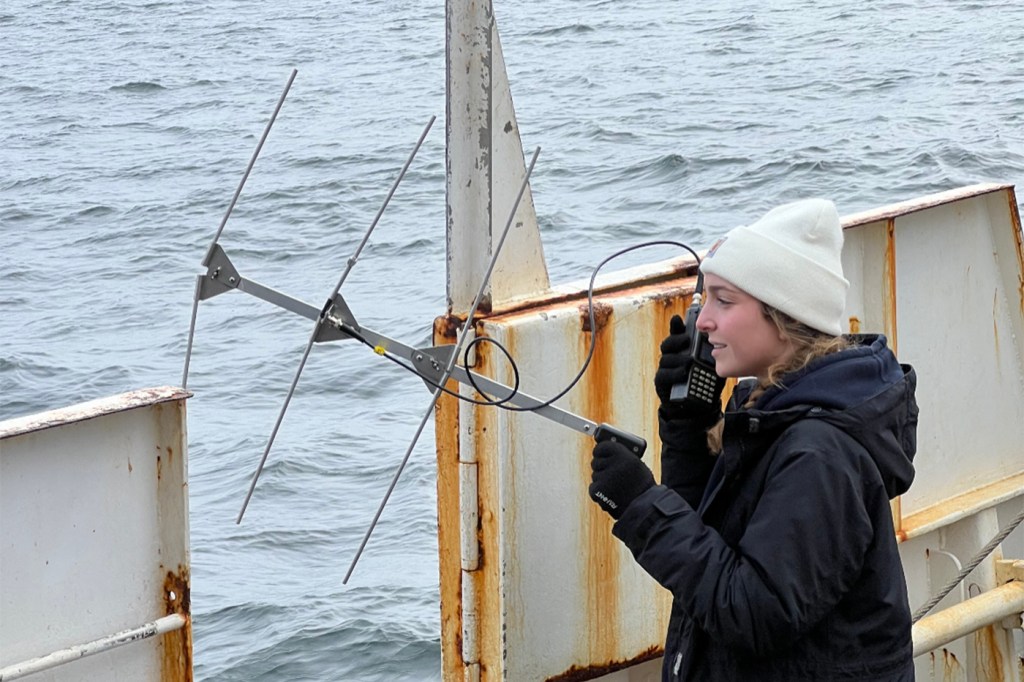

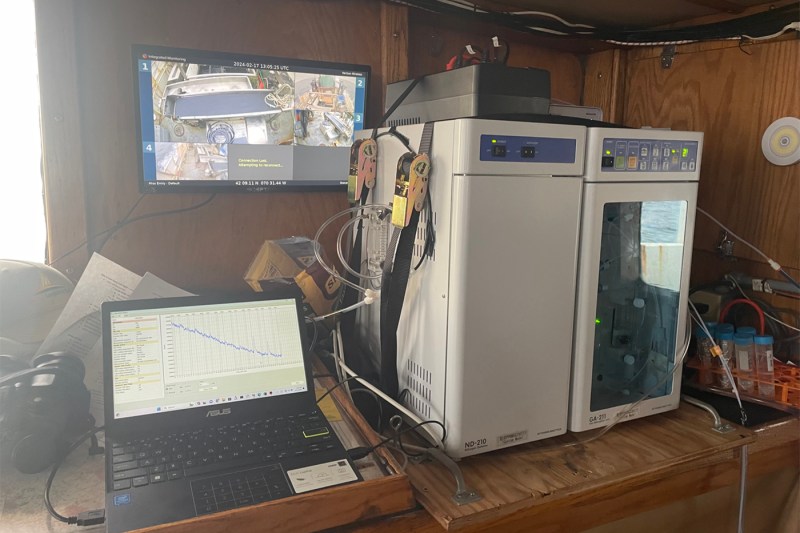

For her co-op at WHOI, she goes on 12- to 14-hour scientific cruises every 10 days or so to collect water samples, look for North Atlantic right whales, and correlate plankton abundance to whale sightings.

“On the cruises we collect DMS, or dimethyl sulfide, which is a gas in the water released by phytoplankton,” Benjamin says. “North Atlantic right whales eat zooplankton, zooplankton eat phytoplankton.”

When phytoplankton are eaten, they emit the gas DMS, she says.

“So our theory in the lab is that the more DMS gas that is detected in an area, the more zooplankton, aka whale food, there’ll be in an area, and the more whales there will be in the area,” Benjamin says.

“Our hypothesis is that whales can detect this gas — we don’t know how. We think they can detect it and navigate toward it to get more food.”

During cruises to collect water samples containing DMS, Benjamin has seen dozens of endangered North Atlantic right whales migrating through Cape Cod Bay.

“They’re so impressive,” she says.

“We see them skim feeding a lot,” Benjamin says, which is when the whales feed by opening their mouths while swimming slowly along the water’s surface, using their baleen to capture tiny zooplankton.

“We see lots of fluking, when their tails come out of the water and even some breaching, which is really uncommon for right whales.”

Counting penguins

One of Benjamin’s other main tasks is counting Adelie penguins in a colony in Antarctica via drone images to determine the colony’s density.

“It’s counting from way above,” she says. “But the drone images are really high resolution, so when we go through the images we are able to see individual penguins and their behavior,” including keeping eggs warm and safe from predators.

“When two penguins are really close to each other, this is typically two adults swapping turns sitting on the egg,” Benjamin says. “We assume that we are catching them swapping turns nesting and protecting the egg while the other is about to leave and search for food.”

Featured Posts

While melting Antarctic ice threatens the long-term survival of penguin colonies, the island Benjamin’s lab has been studying, which she is not allowed to name, has been seeing a population explosion.

“We should be seeing a downward trend, but we’re seeing a dramatic upward trend. We have a couple of different hypotheses why,” says Benjamin, who adds that she’d like to take on the project of testing a hypothesis with past data and seeing how it pans out.

A hungry octopus is an angry octopus

Benjamin’s duties also include working with acoustic data from hydrophones set up in the Arctic and determining what marine mammals are passing by the sound of their calls.

During her first co-op, with the Marine Biological Laboratory, also located in Woods Hole, she worked as a cephalopod specialist, meaning she helped care for octopus and squid.

She also got to be part of a preliminary study about how the genetics of a certain species of squid might impact its longevity and fecundity.

“It was really cool,” Benjamin says.

She also discovered how feisty octopus could be if they haven’t been fed in time.

“I’ve been squirted a few times,” Benjamin says. “They have personalities. They definitely have emotions.”

Future plans

Benjamin plans to graduate next year and hopes that a job at WHOI is in her future. She says she’s also interested in exploring Northeastern’s Three Seas program that takes students to different ocean environments around the world.

The co-op with WHOI gave her the chance to see lessons from the classroom translated into real world work, Benjamin says.

“This is what I envisioned when I started taking marine biology classes,” she says.

“In college you learn the nitty gritty aspects and the chemistry of it all. What I really want to do is work with these animals that are so fascinating. It’s such a great opportunity to be able to do that before graduation.”